![]()

By Zachary Horner, Chatham News + Record Staff

(Editor’s note: this is the fourth of a five-part series about Chatham County’s response to the opioid crisis.)

In a way, the Chatham County Library is partly responsible for kickstarting the recent public conversation on the opioid epidemic.

Rita Van Duinen, the branch manager of the Chatham Community Library in Pittsboro, had a daughter who graduated from Northwood High School and was classmates with Boone Cummins — who died from an overdose that involved benzodiazapines. The same class of drug which experts say are often paired with opioids when consumed. Van Duinen had watched a documentary called “Kids,” produced by Northwood alum and her daughter’s classmate Zoe Willard.

“After seeing Zoe’s documentary and sharing it, I thought, ‘We’ve got to have a conversation about this,’” Van Duinen told the News + Record in February.

Now, the library has hosted two events — one in Pittsboro on February 16 and one in Goldston on April 4 — with plans for a similar event in Siler City in the near future. It’s part of what community leaders are pushing primarily to help combat the opioid epidemic: awareness and education.

Can’t ‘arrest our way’ out of it

In 2016, Chatham County Sheriff Mike Roberson and county Public Health Director Layton Long began discussing possible plans of attack to opioid use in Chatham.

“[These are] drugs they cannot physically stop taking,” Roberson said at the April 4 event in Goldston. “We are not going to be able to arrest our way out of this problem, and we’re not going to be able to afford to treat our way out of this problem.”

Roberson and his department initiated a working group of law enforcement officials and community leaders to raise awareness of the opioid issue. They put up billboards on U.S. 421, created public service announcements and even held an opioid epidemic summit two years ago. Law enforcement agencies got Narcan, an opioid-reversing drug, free through the health department.

Most important of those efforts, Roberson says, is the education. Simply arresting dealers and users of illegal drugs is not enough.

“The community has to fix this problem,” he said. “We know that education and prevention has to be where our money is spent. It is going too big and the wave will be too large to say, ‘Arrest them and treat them.’”

One place that education has been fixed is in the county school system. Tracy Fowler, the district’s director of student support services, said the district follows standards set up by the state to educate students on the dangers of drugs, called the North Carolina Healthful Living Standard Course of Study. The district has also implemented programs like Too Good for Drugs, a risk-mitigation program for eighth graders designed to help students develop skills to make healthy choices and resist peer pressure. Additionally, students from kindergarten through second grade go through Second Step, which utilizes social-emotional learning designed to decrease problem behaviors.

“If we have kids in a good place socially and emotionally, they tend to have better foundation to deal with life,” Fowler said. “Just starting with age-appropriate conversation with things that are harmful to your body to the point that you talk about things like drugs as you get older.”

She added that the district takes the 17 percent of Chatham high school students misusing prescription pain medicine as a “concern,” and CCS “want(s) to be part of the solution.”

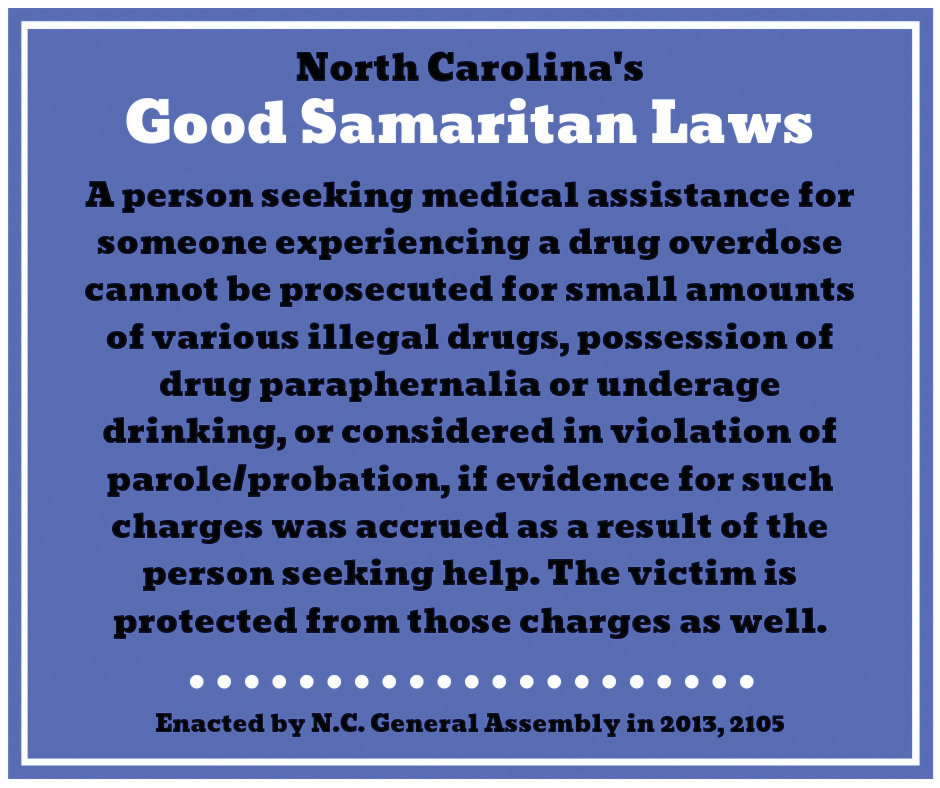

Being a good Samaritan

Graphic by Zachary Horner

In the written histories of Jesus Christ in the Christian Bible, Jesus tells a parable about a man who was robbed, beaten and left for dead. Both a priest and a Levite, a religious man in Jewish culture, passed the man by, but a Samaritan — an outsider in Jewish culture — picked the man up and took care of him on his own dime.

In Chatham County, two parents have spent the last couple of years spreading awareness and fighting for improvements to a law nicknamed after that Good Samaritan.

Bridget O’Donnell’s son Sean died on June 4, 2017, after a pill overdose. His friends made a bet concerning the consumption of vodka and when Sean passed out — scared of potential repercussions — they left him. He later died.

“After Sean died, I just started asking what can we do to prevent this going forward — and that’s when I learned about the Good Samaritan Law,” O’Donnell said. “We have a law in North Carolina that can help so many people. It’s such a simple law that can help save lives, but it’s our mission to make sure that everyone is aware of the law and to make improvements to it.”

First passed in 2013, the law provides limited immunity for people who seek medical assistance for those experiencing a drug-related overdose. Found in N.C. General Statue 90-96.2, the language exempts those reporting the overdoses and those experiencing the overdoses from prosecution for certain amounts of drug possession if evidence for the possession was obtained during medical response to the overdose.

O’Donnell and Julie Cummins, Bonne Cummins’ mother, and their daughters have spent a lot of time over the last couple years pushing for awareness of the Good Samaritan Law and positive changes. A bill currently in the legislature would clarify and extend immunity to the overdoser, and there is other legislation being pushed for as well.

Fowler said the school district has added education about the Good Samaritan Law to its health and PE curriculums, and Roberson briefly discussed the law at the April 4 event.

“It says if you do the right thing to save someone’s life, we’re not going to charge with you a little bit of drugs,” the sheriff said. “Don’t let that stop you from stopping someone from dying.”

Down on the MAT

Another attempt to help the opioid crisis is pointing individuals to treatment, particularly medication-assisted treatment, or MAT.

In his book “Heroin Death: How to Stop the Opioid Crisis,” Chatham County resident Dr. Joe Mancini argues for the use of medicine like buprenorphine. First available in 2013, the drug is designed to have minimal to no withdrawal symptoms and provide pain relief 30 times stronger than morphine, Dr. Mancini writes. Buprenorphine is an opioid, which concerns some doctors. But Dr. Mancini argues it may be a key to stopping the crisis.

“It cannot cause an accidental overdose, except in very unusual circumstances when it is combined with another depressant in a very high dose and injected intravenously,” he wrote. “If taken in a chronic pain situation, it is also less likely to cause increased neuropathic pain.”

Chatham Recovery Program Director Anna Stanley, right, chats with front desk administrator Christy Wells on a recent morning at the organization’s clinic in Siler City. (photo by Zachary Horner)

Anna Stanley, the program director for Chatham Recovery, an opioid treatment clinic in Siler City, spoke at the April 4 event in Goldston. The clinic’s program offers daily doses of buprenorphine and methadone — another opioid that “calms down” receptor sites and ends cravings, Stanley said — as well as individual and group counseling sessions. Stanley argued that pursuing medication actually raises the likelihood that addicts will attend counseling.

“It’s very challenging when someone is in such bad withdrawal,” she said. “We’ve got to get them stable on that medication so that we can engage with them in behavior changes.”

The National Institute on Drug Abuse states that medicines like buprenorphine, also called Suboxone, and methadone “are effective for the treatment of opioid use disorders,” and that they should “be combined with behavioral counseling for a ‘whole patient’ approach.”

Because the medicines offered are opioids as well, Stanley said, some people are worried that they might be “trading one addiction in for another,” but she refutes that.

“Clinics are not licensed drug dealers,” she said. “We have a lot of regulatory bodies that come in and inspect our clinic regularly.”

In the final part of the Chatham N+R’s opioids series, coming May 23, read about a Chatham resident’s personal story with addiction — and more about what you can do to help fight back.

Chapelboro.com has partnered with the Chatham News + Record in order to bring more Chatham-focused stories to our audience.

The Chatham News + Record is Chatham County’s source for local news and journalism. The Chatham News, established in 1924, and the Chatham Record, founded in 1878, have come together to better serve the Chatham community as the Chatham News + Record. Covering news, business, sports and more, the News + Record is working to strengthen community ties through compelling coverage of life in Chatham County.