![]()

By Zachary Horner, Chatham News + Record Staff

(Editor’s note: this is the second of a five-part series of stories by the Chatham N+R about the opioid crisis, its impact on Chatham County and possible solutions.)

While discussing the drivers of the opioid crisis April 4 at an event at Goldston’s Town Hall, Casey Hilliard, a health policy analyst with the Chatham County Health Department, listed a few of the instigators.

The reality of lethal synthetics. Drug use being viewed solely as a moral/legal issue. The over-prescription of pills.

She spoke about each, but got blunt on one topic.

“Pain is real,” she said. “I don’t think the medical system has figured out how to address pain appropriately while at the same time removing opiates. That’s where you see folks turning to heroin and other things.”

The opioid problem could be described as a problem of pain that’s stretched out for thousands of years, but has found a footing in the 21st century, for a few reasons.

The addictive nature

Casey Hilliard, health policy analyst at the Chatham County Health Department, speaks to a group about opioids April 4 at Goldston Town Hall.

The earliest record of opium, the base substance in opioids, is from 3300 B.C., according to “Heroin Death: How to Stop the Opioid Crisis,” a book by Chatham County resident Dr. Joe Mancini. Mancini spent his career in family medicine before spending the last 10 years in addiction medicine.

Opium comes from the pulp of the poppy seed plant. Once it is dried, it can be smoked or ingested. For thousands of years, it existed in that form and became a common trade item. Morphine, a commonly-used painkiller, was derived from opium in 1804, kicking off a nearly 200-year period of the development of new medicines used to treat pain — oxycodone, Percocet, Oxycontin, Vicodin, fentanyl and more.

In “Heroin Death,” Mancini lists three reasons opioids are addictive: they’re the only “mood-altering substance that give direct pain relief,” they “provide an intense degree of euphoria,” and withdrawal symptoms are so “extremely painful and intense” that they “make it very difficult not to seek another dose to get relief.”

Anna Stanley, the program director of Chatham Recovery, explored the depths of the science of addiction at the April 4 meeting in Goldston. She said that when opioids are taken, “the brain starts to add opioid receptor sites.”

“Over time, you need more and more because you’ve got more of these receptor sites that are screaming out, saying, ‘I need more opiates,’” she said.

Not getting that fix can lead to the aforementioned withdrawal.

“It’s not deadly for most people, but you pretty much feel like you’re going to die,” Stanley said. “You just feel really bad, and the only thing that can make you feel better is to take another opiate.”

The problem of pain

Dr. George R. Hansen of the Sierra Vista Regional Medical Center and Dr. Jon Streltzer of the John A. Burns School of Medicine at the University of Hawaii penned a report called “The Psychology of Pain” for the journal of the Emergency Medicine Clinics of North America in 2005. In the report, the pair wrote that the same centers in the brain activated by pain are activated by social rejection. Getting turned down for a date or left out by friends produces the same psychological response, it appears, as pain.

Drs. Hansen and Streltzer also wrote about the effect of chronic opioid use on pain, saying that continual use can lead to “enhanced pain sensitivity.”

“Patients dependent on daily doses feel worse when the medication wears off, and closer to baseline levels of pain temporarily when they take it, even though the overall pain condition fails to improve,” the report said. “These patients may see opioids as necessary for survival.”

Opioids, by their very biological make-up, are designed to become “necessary.”

Layton Long, the county’s public health director, spoke briefly on the idea of pain at the Goldston meeting.

“We were told and we were trained that you should not ever be in pain,” Long said. “So we placed a demand on the doctors for us to not be in pain. That’s not the reality of life.”

Too many pills

One of the common problems associated with the opioid epidemic, as cited by Hilliard, is over-prescription of the pills.

One of the common problems associated with the opioid epidemic, as cited by Hilliard, is over-prescription of the pills.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, opioids are often prescribed for pain after surgery or injuries, and for health conditions like cancer.

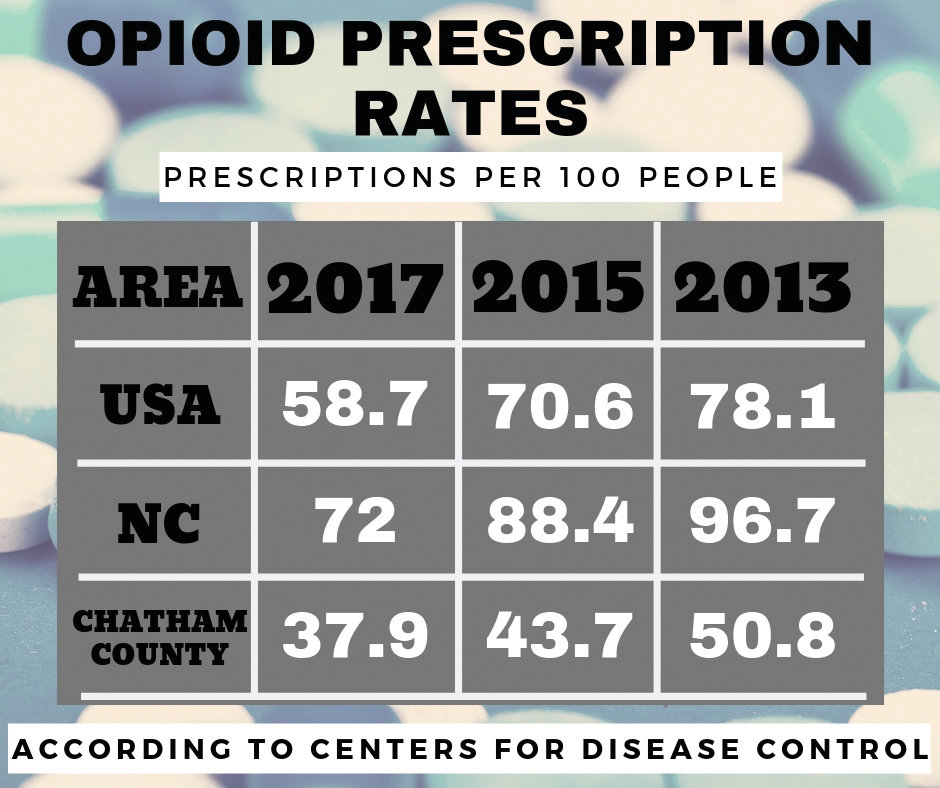

The CDC said the United States saw 58.7 opioid prescriptions written per 100 people in 2017. In North Carolina, the number was 72, while Chatham saw just 37.9. In 2013, just four years before that, the rates were 78.1 in the country, 96.7 in the state and 50.8 in the county.

While the overall number of prescriptions has been declining, the amount of opioids in morphine milligram equivalents (MMEs) prescribed per person — a way to calculate opioids taking into account type and strength — is three times higher than it was in 1999.

While Chatham County’s number two years ago is on the low end, surrounding areas aren’t all in the same boat. Just to Chatham’s south, Lee County’s opioid prescription rate is 114.2 per 100 residents — enough for each citizen to have at least one — and Moore County had 102.8 prescriptions per 100. Wake County’s rate was 47.5 per 100 residents, while Durham had 41.6 and Orange had 36.7.

According to a report from doctors and researchers from the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine in Baltimore, there were 240 million opioid prescriptions in the U.S. alone in 2015. The authors of the study — surgery and health policy professor Martin A. Makary, surgeon Heidi N. Overton and researcher Peiqi Wang — wrote that physician overprescibing was “a major contributor” to the epidemic.

“The opioid crisis is the latest self-inflicted wound in public health,” the report’s abstract states. “Too many people are leaving the hospital with bottles of opioid tablets they don’t need.”

Sgt. Ronnie Miller of the Chatham County Sheriff’s Office said at the Goldston event that the availability of these pills is one of the department’s main concerns.

“There’s a bunch of pills in a lot of medicine cabinets,” he said. “What we would like to see happen, through education, is for people to realize how powerful and destructive these drugs can be.”

Coming in Part Three next week: a look at the use of heroin, benzodiazepines and opioids in Chatham County.

Chapelboro.com has partnered with the Chatham News + Record in order to bring more Chatham-focused stories to our audience.

The Chatham News + Record is Chatham County’s source for local news and journalism. The Chatham News, established in 1924, and the Chatham Record, founded in 1878, have come together to better serve the Chatham community as the Chatham News + Record. Covering news, business, sports and more, the News + Record is working to strengthen community ties through compelling coverage of life in Chatham County.