How should we tell the history of the American South?

In the last few decades, new historical research has allowed scholars to reimagine that story from new perspectives. Historians now have a better understanding of the role of women, Native Americans, and people of color – not to mention a better understanding of the vast diversity of the region, from its geography to its people. In addition, recent scholarship has focused on the South’s volatility: far from being the unchanging, traditionalistic agrarian society it’s so often depicted as being, the South has been a place of constant change and radical, sometimes violent transformation. And while we often focus on New England when we discuss America’s early history, new research has revealed that the South was more central to that history than we often think.

All of those insights are present in “A New History of the American South,” a new book from UNC Press edited by UNC historian W. Fitzhugh Brundage.

Click here to purchase the book and read more details.

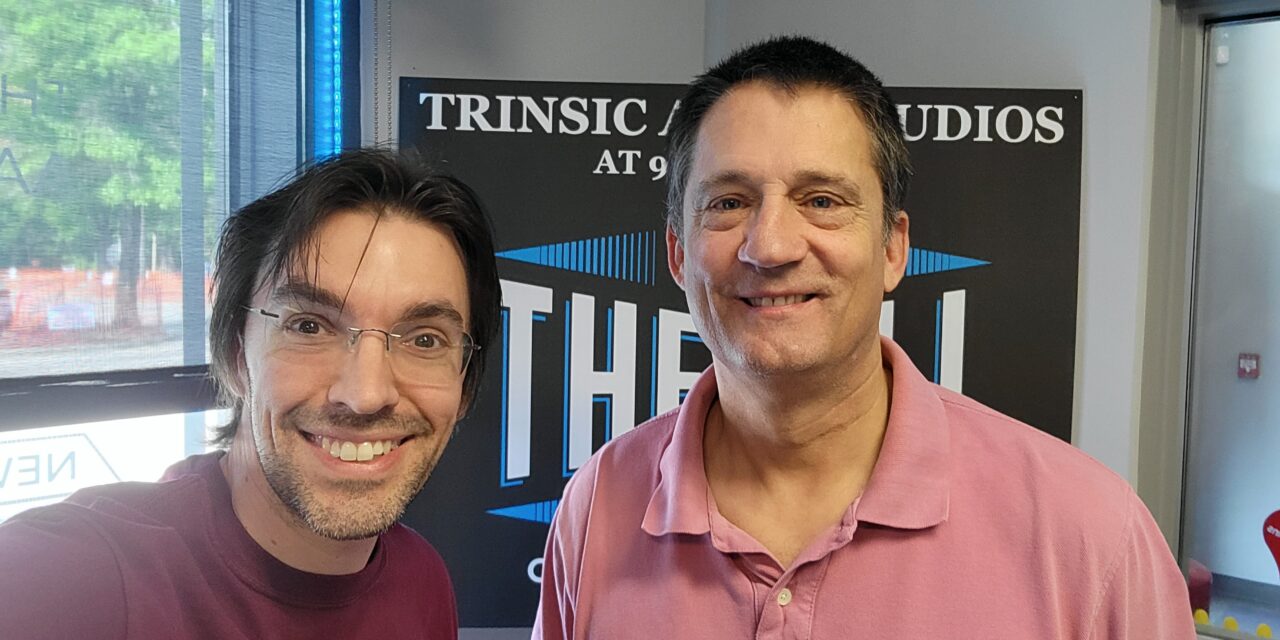

97.9 The Hill’s Aaron Keck had a chance to speak with Brundage this week about the book and the lessons it has to offer.

Click here to listen to their conversation.

Aaron Keck: How did the project come about in the first place?

Fitzhugh Brundage: A wonderful editor at UNC Press, Chuck Grench, (first) came up with the idea two decades ago. Chuck (thought) it was time to bring together the wisdom that had accumulated over the last several decades from a lot of new history, a lot of new scholarship on the American South…and to tell it in a way that we hope is accessible and engaging.

Keck: How does the latest wisdom differ from the previous conventional wisdom? Why do we need a new history?

Brundage: I’ll offer a couple examples. If you go back 30 or 40 years, most of the scholarship on the colonial era or early American history from 1500 to 1800 was written from a northeastern vantage point. There was much less scholarship on the South – and in the last 30 years, wonderful scholarship has been done on the South. It’s been a revolution in what we know. Another example: 40 years ago, there were (only) a couple major books on women in the American South. Over the last 30 years, some of the very finest scholarship in American history has been written about Southern women, White, Black, Hispanic, Native American women. So we know a lot more about women than we did in the past. And I think there’s also been a tremendous amount of work done on the history of Black Southerners – not just during slavery, but also through the Jim Crow era and the civil rights struggle of the late twentieth century. So there’s been an explosion of scholarship on the South.

Keck: The fascinating thing that jumped out to me was – and I think this is the case with any topic – you get a rough knowledge of something and then things kind of fix in your head, as in: “this is what all of the South was always like, this is what all slavery was like.” Very broad categories. And you think of that as fixed in history, always the same – (but) this book really emphasizes the extent to which all of these things are constantly in flux. And there’s all these radical transformations that happen, and they’re the outgrowth of these sometimes violent clashes that happen between widely various different groups of people, (clashes) that could have just as easily gone the other way…

The one that stood out to me was the fight about slavery in Georgia, in the first couple decades of that colony’s existence. We think, “oh, Georgia was (always) a slave state” – but it wasn’t, for 20 years, and there was a fight, and it could have gone differently. That was fascinating to me.

Brundage: I think you’re right. The importance of contingency: events could have gone one or two or three different ways, and they happened to go one way. You’re certainly right about slavery. I think another example is what happened to the Native Americans of the American South. In 1700, the Native American population was substantially higher than that of European colonists. Even a hundred years later, the Native American population had shrunk enormously, but (they) still controlled probably 70 percent of what we think of as the modern South. Over the course of – between, we’ll say, roughly 1750 and 1850 – what was going to happen to that land? Well, we know what ultimately happened – but it could have gone a lot of different directions. And one of the points in this book is to try to suggest why events played out in a specific way they did, and to hint at how they might have gone differently.

Keck: And also just the heterogeneity of the whole region. Like “Native Americans”: there’s so much diversity within that category, and that’s true of every category that we talk about.

Brundage: Yeah. So there’s three big empires competing for the American South – the British, the French, the Spanish – and then you have all of these various different Indian nations, some of whom are quite big and powerful in their own right. And that would continue. We tend to think of the Native American population of the South as being erased – but in the mid-nineteenth century, the Comanche nation was a very powerful nation that was simultaneously fighting against Mexico, the United States, and various other Native American groups, and were themselves creating something of an empire. So yes, it’s a region with a much more fluid history than we tend to think.

Keck: One of the underlying questions in the book is: what even is the South in the first place? How do we define it?

Brundage: Yes. It’s a very knotty question. And the way we ended up defining it…

Keck: (laughing) K-N-O-T-T-Y, or N-A-U-G-H-T-Y?

Brundage: (laughing) You’re right. Both ways.

(We were most interested) in the evolving idea of what the South was: obviously in the 16th, 17th, 18th century, no one was thinking of “the South,” as we think of it. They were thinking of it as just part of the North American continent…so the idea of the South changes over time, quite dramatically. And in many ways, the “South” that we think of came into being after the American Civil War, because it arguably came into formation during the Civil War.

But even then, when the Confederacy was founded, there was more than a third of the population within the Confederacy that was not committed to the Confederacy – namely the enslaved population. So the idea of the South was constantly evolving, until we arrive at something that would be familiar to us after the Civil War. But even now, if we think about it…just think about how much (the South) has changed in the last 30 years. There are places where the “South” of today would be unrecognizable to somebody 40 years ago. That has to do with immigration, from within the United States (and) from outside the United States, and tremendous economic change in certain parts of the South. Then there are other (unchanged) parts of the South, which you’d go back to and say, “oh, now I’m back in the South.” But that’s because we’re holding onto a fixed idea of what “the South” is.

Keck: This is not your first time at the rodeo, you’ve studied Southern history for a long time – so what did you learn, from working on this?

Brundage: I was just actually writing an email to somebody and saying how much I learned. I knew some of the discreet parts from having read the scholarship, but to pull it all together and tell a story from beginning to end – what really did come through to me was a point that you’ve raised, which is (that) the South has been an incredibly dynamic region. And when I say “dynamic,” I don’t necessarily mean “progressive” or something like that. I mean just a region with enormous change. I think to be a Southerner has been to be subject to change, to have to undergo change – not just the change after the American Civil War, for both Black and White Southerners, but (also) the profound changes that Native Americans experienced. The profound change that Sicilians who moved to New Orleans experienced. We continue to think of the South as really very traditional – but it’s just been a region where, if you live here, you better hold on to your hat, because it’s just going to change and change and change.

Chapelboro.com does not charge subscription fees, and you can directly support our efforts in local journalism here. Want more of what you see on Chapelboro? Let us bring free local news and community information to you by signing up for our biweekly newsletter.