At an apartment complex in Concord, North Carolina, Jasmine Hensley is getting ready for the birth of her second daughter. Over the past few months, she’s been shopping for clothes, bottles, and toys – an activity she’s been doing with her four-year-old daughter Peyton.

Among their toy haul is an avocado stroller attachment, a winding lullaby koala bear, and a wooden rattle.

Although these purchases may not seem like they go together, for Hensley they all have one common thread – intentionality.

“That’s been kind of the fun part of doing the shopping, but being very selective with each and every item and getting exactly what I want,” Hensley said. “Versus last time I’m like ‘I’ll take whatever I can get.”

Not only is Hensley being more selective with what she’s buying for the baby, but also with how she’s giving birth.

When Hensley had her firstborn, it was done the traditional way – in the hospital, surrounded by doctors, and with an epidural.

“Last time, there were a lot of things that I didn’t necessarily consent to, but I assumed well this is just how it goes,” Hensley said. “This is standard practice, this is what they have to do.”

This time, she still plans on giving birth in the hospital. However, she wants for it to be without medication and with an additional professional in the room – a doula.

Doulas are emotional, physical and informational support people who help moms give birth on their own terms.

And for Hensley, having a doula also serves another purpose – keeping her safe.

As a Black woman, Hensley goes into the delivery room facing a troubling statistic. In the United States, Black women are three times more likely to die from pregnancy-related complications, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

And a recent CDC report stated that maternal mortality rates for Black women were “significantly higher than rates for non-Hispanic white and Hispanic women.”

Although this is a new report, the statistics within it aren’t. The Black maternal mortality rate has been high for years and continues to increase.

Over the years, researchers have speculated about possible reasons the rate is so high, such as socioeconomic status and access to medical facilities like hospitals. But even when these factors are controlled, Black mothers are still dying at high rates, said Dr. Alison Stuebe, a UNC maternal-fetal medicine subspecialist and professor.

“There’s some data in New York City that a Black woman with a graduate degree is more likely to die than a white woman who hasn’t finished high school,” Stuebe said. “And so, it’s not about one’s education or one’s socioeconomic status… I think a lot of it is about structural racism.”

Hensley’s doula, Tashona Winslow, says she also thinks the main reason is bias, which can come in many forms . Doctors may suggest interventions because they put Black women into higher risk categories for certain diseases. Or doctors’ education may lead them to believe that Black women respond to pain differently.

“I think one of the biggest challenges is being heard or believed,” Winslow said. “Some providers were taught that Black and Brown bodies experience pain differently than white bodies do… because there is an assumption that I’m tougher or something along those lines.”

Implicit biases like this are why Winslow suggests that mothers have another person with them anytime they visit a doctor.

“If you go in by yourself, there’s a chance that your care providers may just kind of roll you through the process,” Winslow said. “When there’s other people around, whether it’s a mom or whether it’s a doula, the professional in the room tends to slow down and be mindful, because there’s other eyes around, there’s other people around.”

Doulas, in particular, have had promising results in relation to lowering the Black maternal mortality rate. In 2022, a study done in California found that Black women who had doulas were more likely to have full-term births, had fewer C-sections, and had a lower risk of developing postpartum depression.

Part of Winslow’s mission as a doula is to make every mom feel safe when giving birth. And when moms don’t feel that way, she wants to ensure their doctors hear them.

But there is only so much that an individual doula can change. That’s why UNC-Chapel Hill and North Carolina A&T have formed a new collaboration to address bias in maternal health care statewide – though a project called the BELIEVE program.

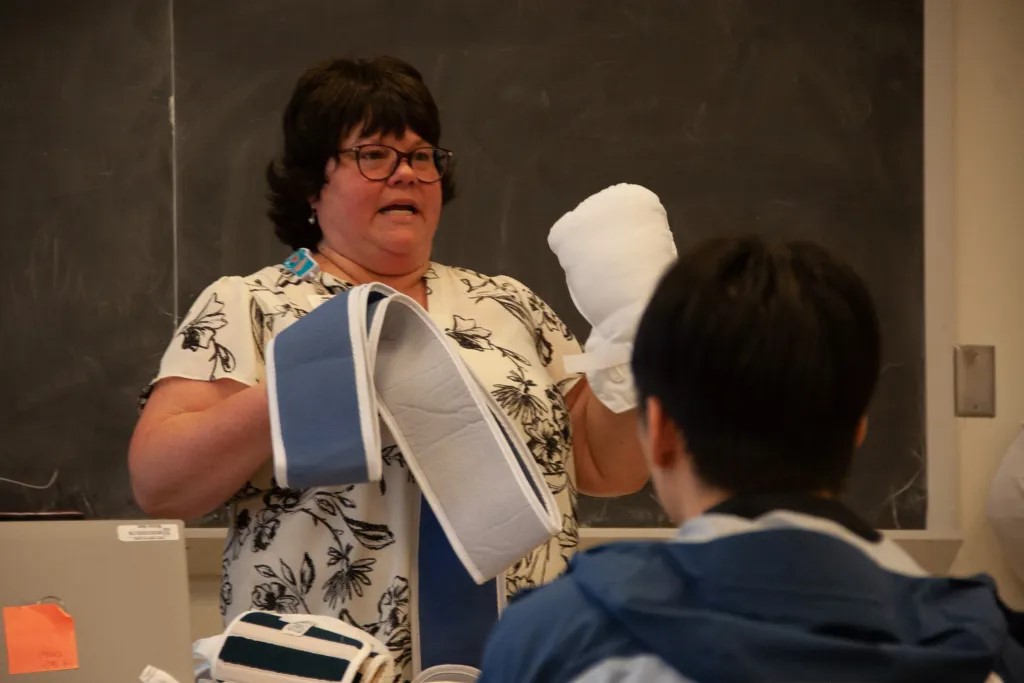

Also known as Building Equitable Linkages with Interprofessional Education Valuing Everyone, BELIEVE was created by maternal healthcare professionals Kimberly Harper and Janiya Williams.

Dr. Stuebe is also a member of the BELIEVE research team. She says Black women can face disparities in the language used in their health records, the number of visits by lactation nurses and even pain management.

“We found that at UNC, Black women have higher pain scores than white women after C-sections, but get less pain medicine,” Stuebe said.

Findings like that will shape the direction of the project, which will start with surveying maternal patients and healthcare workers.

Stuebe says the research team will use the results from the surveys to develop a curriculum centered around every mother feeling seen, heard, and valued.

Eventually, the curriculum will be translated into trainings and simulations both for doctors and medical students.

The final phase of the project will be real-life implementation in four hospitals across the state – North Carolina Women’s Hospital, Rex Hospital, Moses H. Cone Memorial Hospital and Alamance Regional Hospital. Stuebe said the hope is that they see improvements in their measurements so that one day the curriculum could become standard training.

“Health is not just about going to the doctor or going to the nurse practitioner or the midwife,” Stuebe said. “Health is a positive state of wellbeing. An important piece of that is that when something is physically wrong that they have the full spectrum of opportunities available to them and feel comfortable seeking that out.”

Back in Concord, Hensley said she is glad that she was able to hire a doula and that working with Winslow has already made her feel more comfortable and in control of her pregnancy.

“It’s breaking those generational curses, breaking those stereotypes and those molds of just go in and do whatever this white doctor says,” Hensley said. “And I think that is really important to the community as a whole to have that advocate and help turn around what those numbers and those statistics look like.”

This story was originally published on Carolina Connction, the UNC Hussman School of Journalism and Media’s student-run radio program.

Photo via Johnson & Johnson.

Chapelboro.com does not charge subscription fees, and you can directly support our efforts in local journalism here. Want more of what you see on Chapelboro? Let us bring free local news and community information to you by signing up for our biweekly newsletter.