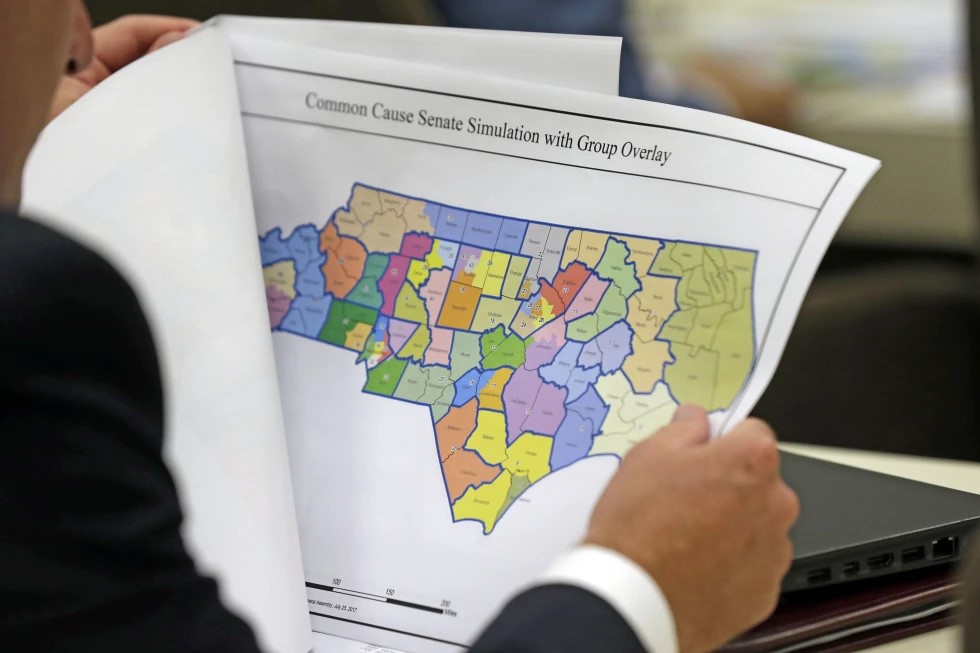

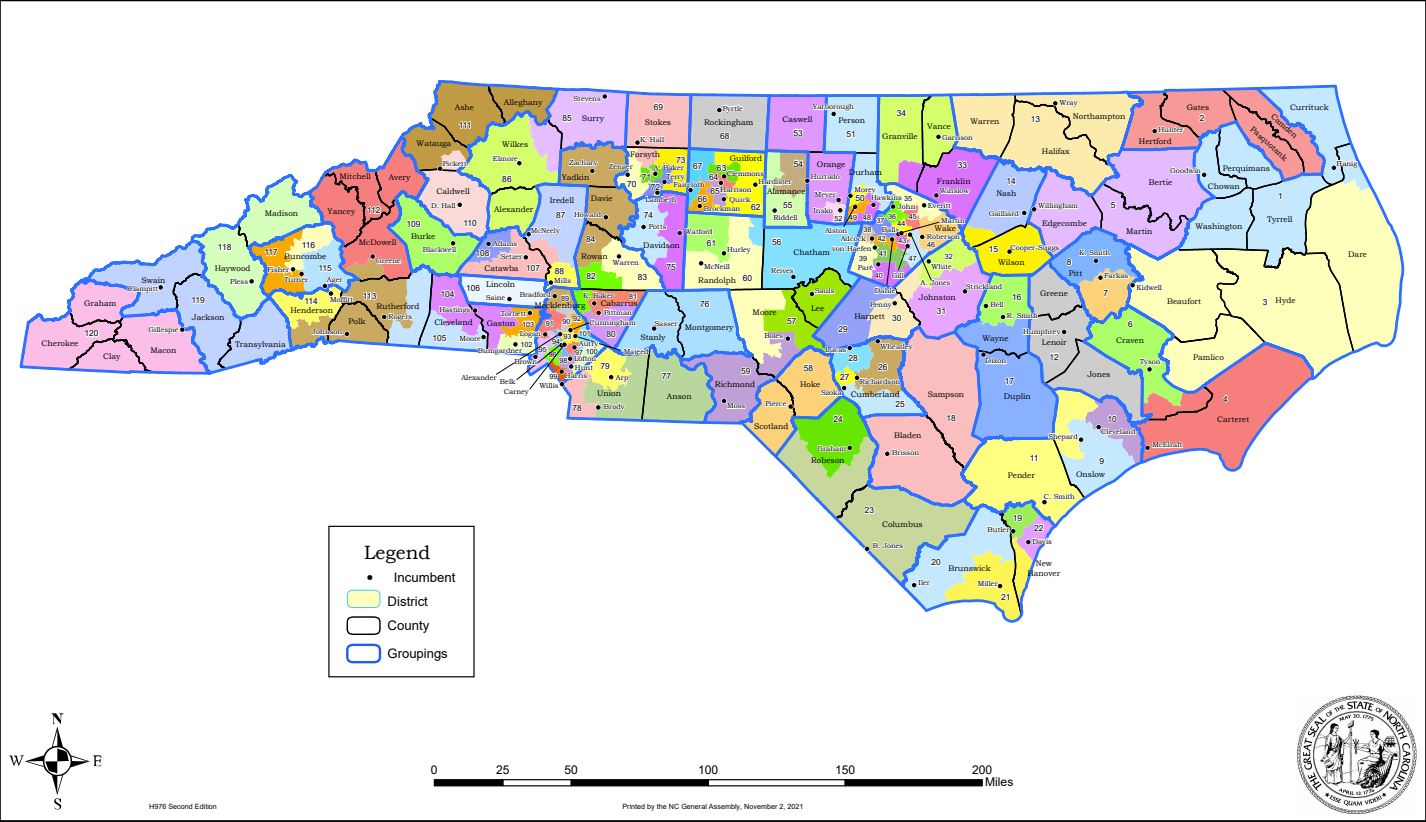

Last week, the General Assembly signed off on a sweeping bill banning most abortions after 12 weeks. It’s not yet clear how North Carolinians might react to the change, but similar measures in other states have proven deeply unpopular, with residents rebelling against GOP lawmakers at the ballot box. Here in North Carolina, though, Republicans may be shielded from voter pushback – because the State Supreme Court just ruled that lawmakers are allowed to gerrymander legislative districts to favor their preferred candidates.

So what can North Carolinians do to ensure their voice is being heard?

Some residents are raising the call for citizen initiatives, which would allow residents to bypass the legislature and propose laws on the ballot directly.

What should we know about citizen initiatives? 97.9 The Hill’s Aaron Keck spoke with Asher Hildebrand, a professor at Duke’s Sanford School of Public Policy, who recently discussed the issue in an online forum hosted by the League of Women Voters.

Listen to their conversation here.

Asher Hildebrand: If the news of the last week is any indication, this is a time where we need to be thinking broadly and creatively about how to ensure the engine of our democracy is working and converting the voice of the people into policy outcomes. And I don’t think anybody’s naive about the political realities we face in North Carolina, (or) the chances of this kind of system being adopted anytime soon. But the fact of the matter is, North Carolina is in the minority of states that don’t have a more robust citizens’ initiative process that allows voters, residents, to put measures on the ballot and to have a direct say in policy issues.

And again, on the heels of the State Supreme Court’s rulings last week on partisan gerrymandering and other issues, as well as the abortion ban, which is something broad majorities of the public oppose – I think it’s a pretty ripe time to be talking about how we make sure that policy outcomes better reflect the will of majority of the people.

Aaron Keck: When we’re talking about initiatives: we have referendums in North Carolina, which are also laws on the ballot that residents can vote on directly, (at least) when it comes to constitutional amendments. But referendums have to be proposed by the legislature, whereas initiatives give residents an opportunity to bypass the legislature entirely.

Hildebrand: Right, and actually there are states where both initiatives and referenda can come from citizens, who generally have to collect a certain number of signatures on petitions to demonstrate the viability. And there are all kinds of devils in the details about who can collect those, how many signatures (are needed), and where they have to come from. But in most cases, there’s a petition requirement, and then they bring (the proposal) directly to the people. In some cases that applies to creating new laws; in other cases, that applies to referenda on existing laws or on the constitution. The difference in North Carolina is that the only way for a referendum to get on the ballot is through the General Assembly. There’s no mechanism for citizens to bring it there directly.

And North Carolina is certainly not the only state that that has that kind of restrictive process – many other states also do, especially in the South – but it is in the minority of states. Most states have some kind of direct democracy mechanism – in some cases, for over a hundred years. In recent years we’ve seen – in cases like Michigan, but also in some pretty conservative states – citizens using that power to make changes on things like partisan gerrymandering and abortion rights, but also on things like the minimum wage, Medicaid expansion, and other issues where the legislature is refusing to act and the citizens say, “okay, well, we’ll just take matters into our own hands.”

Keck: What do we know about the way that initiatives can affect the politics of a state? I know this has always been a really profound way of making government more democratic, (but) I’ve also seen studies that suggest that with the initiative and referendum process, you do run the risk (of having) bills that that target minority groups a little bit more frequently than going through the legislative process.

Hildebrand: And we see that in recent history in North Carolina, where voters in the last decade adopted a ban on same-sex marriage (and a) voter ID requirement. So it’s certainly true that (the process) is not without its risks. But there’s a whole lot of evidence that direct democracy, (the) citizen initiative, increases voter turnout by engaging more people in the process. It advances political equality, by bringing people into the process who wouldn’t otherwise turn out: they (may not) particularly care for the candidates on the ballot, but they might care a lot about the issue that’s going to impact their life directly.

And it’s shown in some cases to reduce polarization, because (it) gets us away from thinking about politics and elections just in terms of ‘Democrats’ and ‘Republicans,’ and thinking about it more in terms of the issues that people care about. In many cases, there’s broad agreement among Democrats and Republicans and independent voters, (and) that’s going to help reduce polarization as well. It’s not without some risks – (but) to quote the philosopher John Dewey, the answer to the many of the problems of democracy is usually more democracy. And this is certainly a moment in our nation’s history where it feels like more democracy is needed.

Keck: I do love being able to host a drive-time morning show where someone can just quote John Dewey and no one bats an eye.

Hildebrand: <laughs> Only in Chapel Hill.

Keck: (This issue is) particularly timely because of the State Supreme Court’s decision throwing open the door to partisan gerrymandering – at least until such time that the same exact issue goes back before a different court with a different makeup, because that’s the way the State Supreme Court apparently works now…

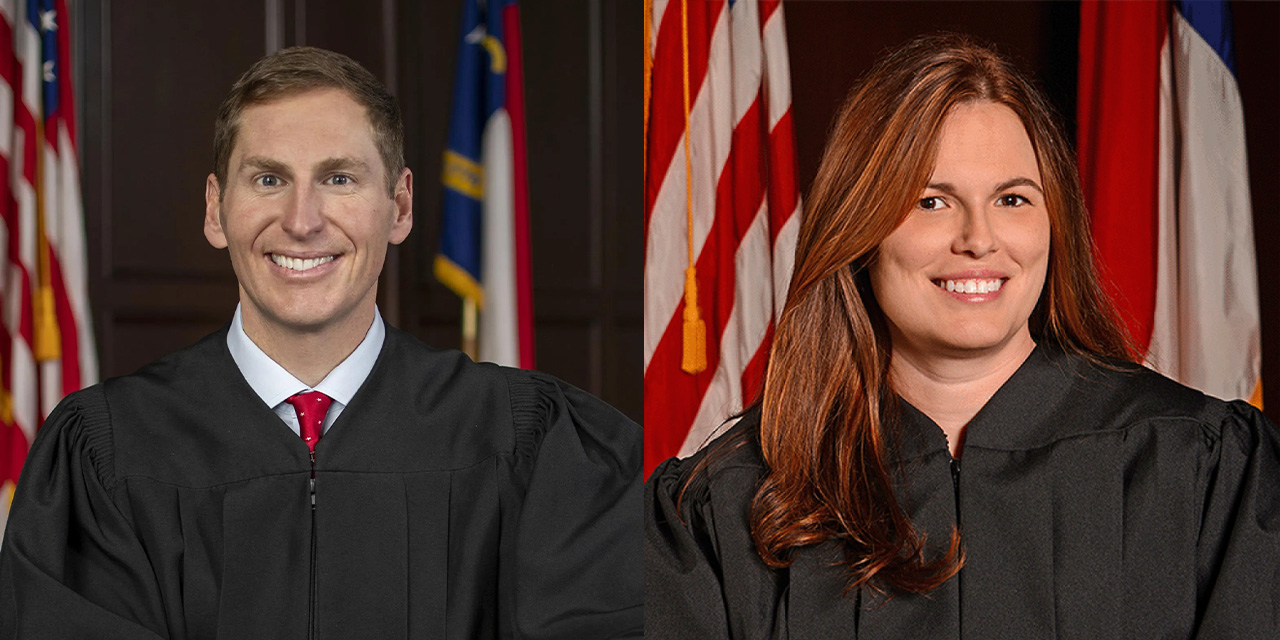

Hildebrand: (And) that was just one of three fairly recent decisions that the, the court overturned. The new court overturned a voter ID decision and a decision that had restored voting rights for over 50,000 North Carolinians who had previously been convicted of felonies. Really in one fell swoop, the current State Supreme Court overturned a lot of the recent advances toward greater voting rights and greater political equality that had been created through previous court rulings.

And while the rulings weren’t particularly surprising…it was nevertheless shocking. In this country, we’re used to the views of the judicial system evolving over time. We’re also used to there being some back and forth, as the courts’ ideological composition changes. If you look at the Earl Warren Supreme Court of the 1960s compared to more recent Supreme Courts, that’s pretty clear. What we’re not used to, though, is a court taking office and almost immediately overturning precedents that were set just months before, purely on partisan grounds. And I think that’s a really alarming precedent for state courts to set. If decisions become entirely a function of which party happens to hold the state court majority, I think that’s a pretty bad place for our democracy to be.

Keck: The underlying question in all of this: in the absence of citizen initiatives, which don’t yet exist in North Carolina, and given the fact that we’re likely moving towards another period of significant partisan gerrymandering – what can residents do now to move the dial, in terms of state legislation?

Hildebrand: Well, that’s the big question. And we don’t have another judicial election until 2026, 2028. The Chief Justice will hit mandatory retirement before then, but now they’re even looking at rigging that by extending the age of mandatory retirement. So it will be some time before the State Supreme Court has a different composition. And they’ve said in their ruling, “well, if citizens care about this, they can go to their legislators and have the legislators act” – but the problem is (that) these legislators are now operating in pretty gerrymandered districts now, and after this next round of redistricting, the districts are going to be highly gerrymandered and probably impervious to a whole lot of citizen advocacy.

So that’s the pessimistic answer. That said, one thing we’ve seen over the last decade and a half or so is that citizen advocacy in support of fair maps, in support of more responsive policies, has made a difference and has moved the needle.

So while the hill appears pretty steep right now for changing the minds of any of our state representatives, we (also) know what happens if we don’t try. And so we have to try. Just to begin shifting the incentives, to make them respond to the idea that citizens are demanding fair maps and a State Supreme Court whose decisions are not totally subject to partisan power considerations. That’s a long-term proposition; I wish I had an easier short-term solution, but it’s the best I got.

Chapelboro.com does not charge subscription fees, and you can directly support our efforts in local journalism here. Want more of what you see on Chapelboro? Let us bring free local news and community information to you by signing up for our biweekly newsletter.