As has been the case in recent redistricting session in North Carolina, the latest round produced maps drawn to heavily favor Republican lawmakers. Each of the congressional, House, and State maps are set to help keep the conservative leadership in power through the rest of the decade. And, unlike before, the state Supreme Court is a majority of Republican justices — who have indicated with their rulings that they are content with that Republican lawmakers’ actions.

N.C. House Minority Leader Rep. Robert Reives II spoke about these latest redistricting approvals, which he and all other Democrats voted against. He discussed about how the maps are the latest example of a legislative power grab by the Republican majority — and his belief that the checks and balances between the three branches of government are no more.

Below is a transcript of Reives’ conversation with 97.9 The Hill Host Andrew Stuckey, which has been lightly edited and condensed for clarity. To listen to the full “Robert’s Rules” segment, click here.

House Minority Leader Robert Reives, D-Chatham, speaks as redistricting bills are debated at the Legislative Building, Tuesday, Oct. 24, 2023, in Raleigh, N.C. (AP Photo/Chris Seward)

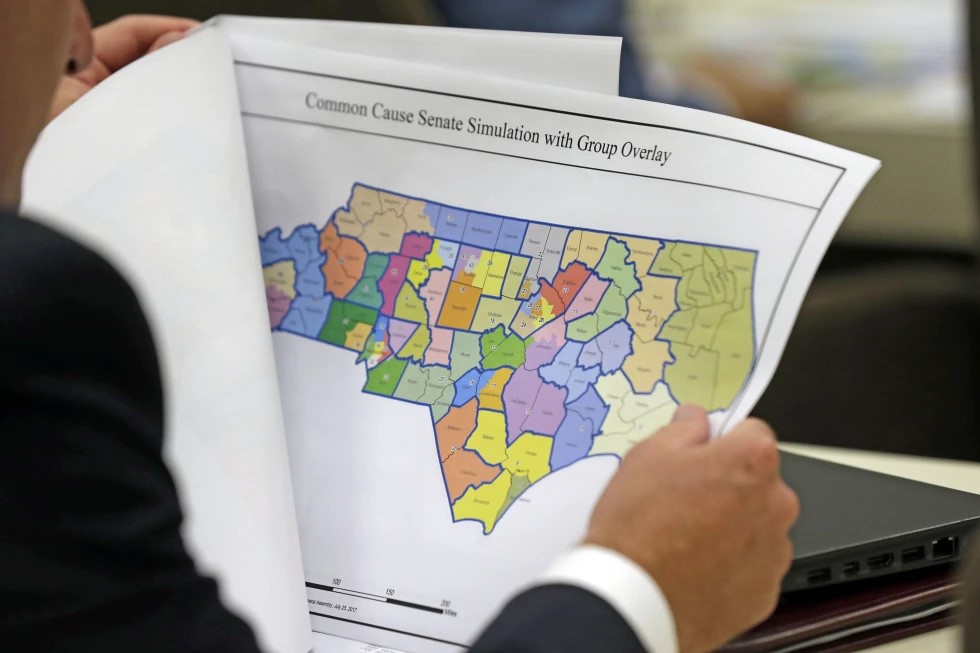

Andrew Stuckey: So, the biggest news that’s happened since the last time we checked in was the release of the new district maps from the legislature. And they’ve been pretty universally looked at as being extreme partisan gerrymandering for the most part. The question — legally — seems to be whether there’s racial gerrymandering involved. So my first question to you… is there racial gerrymandering in these maps?

Rep. Robert Reives: Well, I think there is — and I don’t want to say that in the sense of playing the race card or getting people riled up. Because what happens is as soon as you say the words “racial gerrymandering,” it becomes a lineup of, “You know, we’re not racist.” And it becomes the other line of, “You’re trying to harm Black people.” But the reason I say there is racial gerrymandering is because of the way the parties are lining up now in 2023. It’s almost impossible to do partisan gerrymandering without there being a racial component, whether you acknowledge it, whether you’re intentionally doing [it].

If you’re making a decision about your class of kids and you’ve got 30 kids and the 15 on your left, 14 of them are Black and one of them is white and the 15 kids on your right, 14 is white or white and one’s Black. Obviously, if you make a decision that affects that group of kids on the left, then it also affects them as a racial group within. And that’s nothing about intention, that’s nothing about calling anybody racist. That’s [just] it.

For instance, let’s take a look at the Senate maps. In the Senate district that covers New Hanover County, they took six predominantly black precincts and just moved them out — moved them into a neighboring district, which encompasses Brunswick County. And so those six black precincts now are not going be able to elect a candidate of their choice, period. That’s now over. Whereas in the New Hanover seat, they had the opportunity. It definitely wasn’t guaranteed in that New Hanover seat, it was still a Republican-leaning district, they could affect the outcome. So, looking at areas like that… those are the kind of things that say ‘yes, I don’t think there’s any way around [calling it] that.’ There was partisan gerrymandering, which everybody admits and acknowledges. The question is whether that partisan gerrymandering becomes racial gerrymandering. And as an attorney, I don’t see how you can separate the two.

Stuckey: So timeline wise, what will happen next?

Reives: Obviously, I have no inside information on this part and the Republican party in the General Assembly seems very, very, very comfortable and confident that they know how the Republican State Supreme Court would interpret this if this was to come before them — and how the court of appeals would interpret this if this come before them. I have no idea [how they would rule] because in my mind, the bottom line with judges is your job is just to make a determination about the law. Your partisanship not only shouldn’t matter, but can’t matter if you’re doing your job. With that being said: I think if you were to ask Republican leadership, based on comments they’ve made publicly, they believe this is now a moot issue under the state constitution.

So, what the question is now is whether this is a circumstance where the federal government can step in. I think that question, in my mind, is twofold. Speaking as an attorney… number one, the decision made by the United States Supreme Court about three or four years ago opened up the opportunity to outlaw partisan gerrymandering. Our state Supreme Court, which was a Democratic-led Supreme Court at the time, did not choose to hear [the case]. What they said is they believe this was something that was strictly to be interpreted under the state constitution. So if there’s a partisan gerrymandering claim, I do not believe that the federal law immediately says that there’s no discussion and we can’t have a conversation about this. I do believe that based on that decision right now, the state of the law is that it would naturally go into the state Supreme Court. There’s never been a discussion about whether or not you can have any partisan gerrymandering.

The question is, can you have extreme partisan gerrymandering? The Republican leadership in committee and on the floor acknowledged, “Yes, this is partisan gerrymandering. When we hired this consultant from Ohio to draw these maps, we asked him to draw as many Republican districts as it could. But we believe that is our right under the state law.” And I believe that those areas are still open for challenge. The consideration that’s got to be made is: if you do open those [districts] for challenge, what does that do to — what I think is — a fluid state of law?

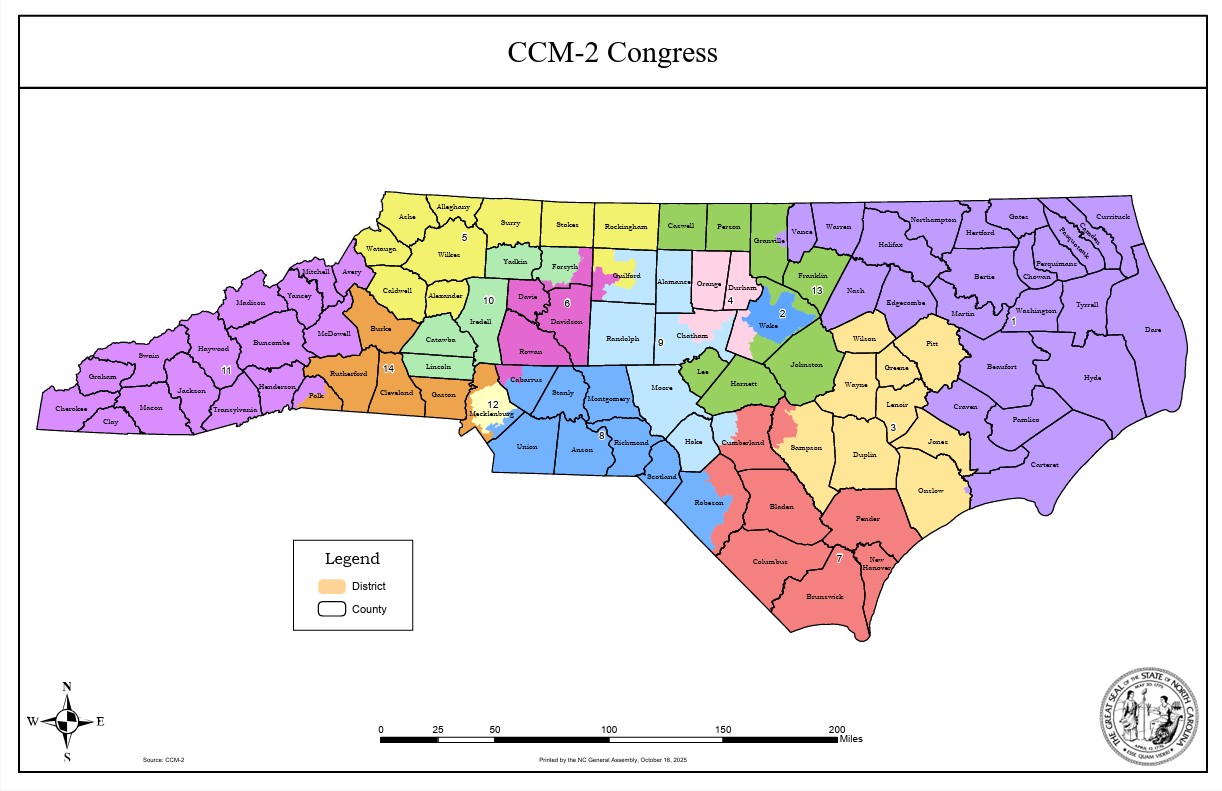

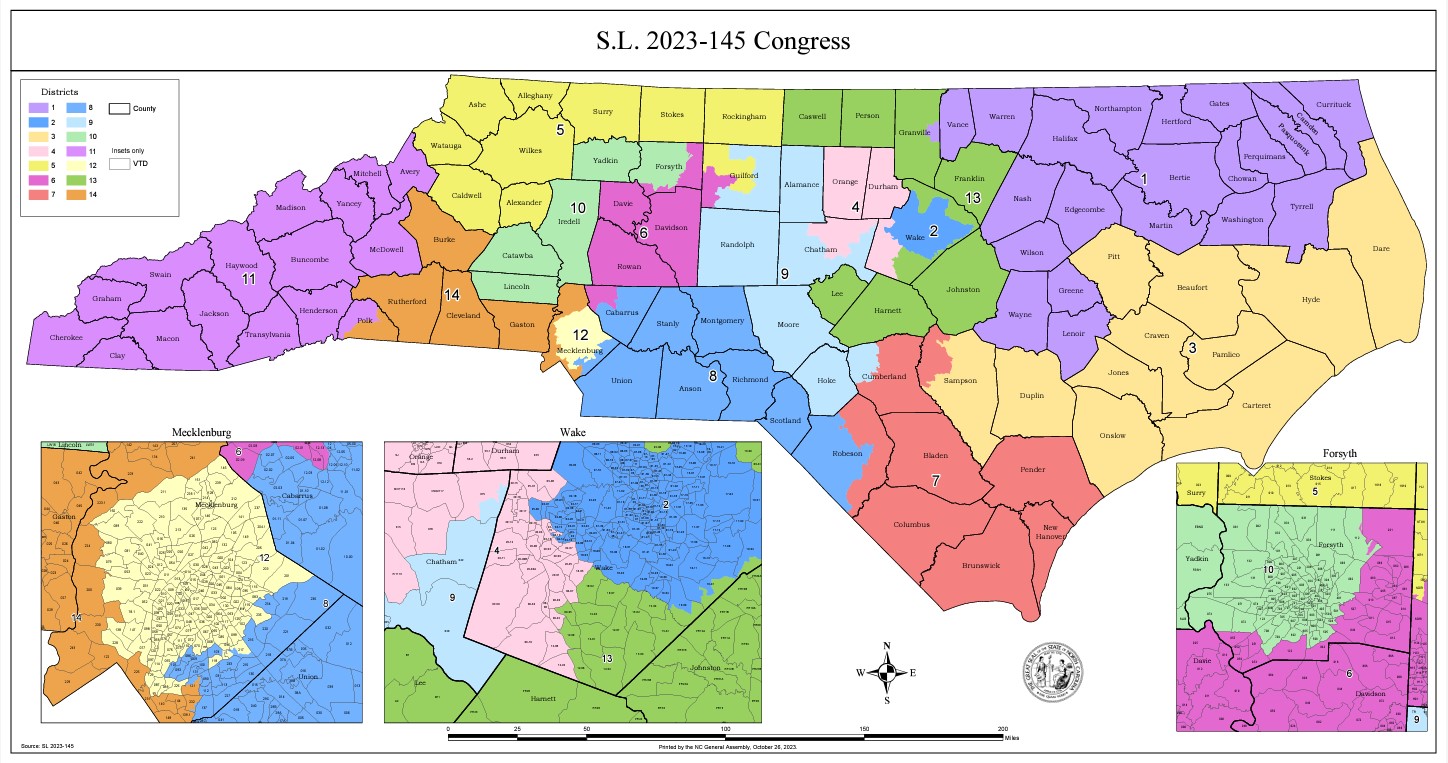

The approved districts for U.S. Congressional elections in the 2020s, as passed by the Republican majority in October. (Photo via the North Carolina General Assembly.)

Stuckey: Could you expand on that? What do you mean by a fluid state of law?

Reives: I just think it’s one of the strange areas in this sense: if you look back historically as different groups have gotten rights in this country, [there were] situations where the courts could’ve easily just stayed with a status quo and they could find a way to stay status quo. But at some point, courts have been bold, have been brave, and have said, “I know this is what people want. I know this is something I could easily say is okay.” But in the spirit of what the Constitution says, we know this isn’t it.

What I know is this: if you went back to the people who wrote a state constitution or the United States Constitution, they weren’t sitting around thinking, “You know, 300 years from now they’re going to have computers so good that they can draw maps down to streets and neighborhoods, and tell us by an algorithm how somebody’s gonna vote.” That’s not what they intended when they had legislators drawing these maps. At this point in time, the judiciary are only backstop… and I’m going to choose to believe they’re going to do the right thing.

Stuckey: One other thing about the General Assembly… obviously these maps have kind of taken up a lot of the attention and the air in the room since they came out. What else is going on at the General Assembly that has got your attention right now?

Reives: Well, the scary thing is the takeover of the boards and commissions. I mean, right now we have become the most powerful general assembly in the entire country. We have effectively, in my mind, eviscerated the separation of the three branches. What we have done is the governor can still go around, cut ribbons and make job announcements… but outside of that, there’s just no separation. By taking the executive branch’s ability to do executive functions, I don’t know how you can pretend they’re still an executive branch. That takes us to the judiciary, and it’s incredibly concerning how it appears the judiciary has been co-opted. I mean, there’s some parts about what we have going on that I think even the most kindhearted and naïve people in the world would say, “It looks really bad about how incestuous those relationships seem between our leadership and our legislature, and our leadership and our judiciary.” With no backstop, it’s actually gotten kind of frightening, to be honest.

I talked to a reporter a couple weeks ago and he says, “Well, it always sounds like Democrats are saying that sky’s falling.” I’m not saying sky’s falling… the sky has fallen. It’s a matter of whether we make the effort to try to right the ship again. Because right now, whoever the Speaker of the House is and whoever the Senate leader pro tem is, those two people are the most powerful people in your state by far. They determine every area of policy. They write the law and now they have the right — by taking over the appointments for boards and commissions — to determine how those laws are executed. And by the relationship they have with the judiciary… they now control how [laws] will be interpreted. When you really think about it, behind those two, the next most powerful person is the chief justice. And then at the end, coming far behind, you’ve got the governor — who is the person most susceptible to their job being determined by the will of the people. That is the one person out of the four I’ve just mentioned who is actually open not only to a statewide election, but a statewide election where any citizen out of our 10.5 million could run against that person. You know, if you’re running for state Supreme Court Chief Justice, you still have to be a lawyer. That is a pretty limited number of people who can even run for that position. The governorship is the only one that everybody can run for and everybody can make determination whether or not that person keeps their job.

Stuckey: The separation of powers is a pretty core tenant of the U.S. Constitution. What’s the likelihood this ends up before the Supreme Court, this power grab from the legislative branch?

Reives: I really don’t know. I’m completely candid. Unlike what we present sometimes as a legislature, we don’t know everything. I mean, to me, it seems like this is one of those areas where the federal government and the federal judiciary has to step in, because this is where we were 100 years ago. This is where we were 200 years ago. This is where we were 60 years ago when we had some pretty serious rights violations going on in states that did not seem to want to comply with the basic tenant that all men and women are created equal. All people deserve voice in their government. To me, we have gotten to that stage [again].

Stuckey: Is there anything else you wanted to mention that we haven’t gotten to yet?

Reives: What I would say is that we talked a lot about doom and gloom, but I can also talk about the bright spots. One, obviously, we’re still a fast growing state. We’ve still got a great business atmosphere. We’ve still got great people that live here. And ultimately when you look at the numbers, no matter how maps to gerrymandered, no matter how much effort is done to keep people from voting, we’ve got the numbers to make this a wonderful government and a wonderful state to live in — if we choose to participate in our government.

Chapelboro.com does not charge subscription fees, and you can directly support our efforts in local journalism here. Want more of what you see on Chapelboro? Let us bring free local news and community information to you by signing up for our biweekly newsletter.