A graduate student at UNC’s journalism school recently saw one of his pieces reach finalist consideration for the Pulitzer Prize.

Daniel Johnson, who is part of the Roy H. Park Fellowship Program at the Hussman School of Journalism and Media, partnered with Dave Philipps of the New York Times to publish a story examining the ties between recent long-range artillery crews, a high rate of deaths by suicide, and PTSD symptoms. The pair of reporters found an old report confirming these soldiers suffered traumatic brain injuries from the constant blasts of their guns, called blast overpressure — and saw their work nominated as a finalist for the 2024 National Reporting Pulitzer.

Johnson recently spoke with 97.9 The Hill’s Andrew Stuckey to talk about working on the piece, its national recognition and reception, and his own experience with artillery units in the military. Below is a transcript of their interview, which has been lightly edited for clarity and brevity. A full version of the conversation can be heard here.

A portrait of Daniel Johnson, who is a Ph.D. student in the UNC Hussman School of Journalism and Media. Johnson researches mental health in the military, with one of his latest widely-recognized pieces being a Pulitzer Prize finalist. (Photo via John Gove/UNC Research.)

Andrew Stuckey: I definitely want to get into your reporting, but I’d like to back up a little bit first and just have you tell us about your journey. How did you get to UNC-Chapel Hill, and then how did you get onto this article?

Daniel Johnson: So, I’m originally from North Carolina. I’m an army brat. My dad served at Fort Bragg. I went to undergrad at Appalachian State University where I did ROTC and then commissioned into the U.S. Army. In about 2016, I deployed to Iraq as part of the 101st Airborne Division where I served as my unit journalist. During that time, I basically covered our anti-ISO operations, what the soldiers were doing, all that good stuff for the military. But one of the things I was part of… I worked a lot with artillery units that fire high explosive shells at the enemy, and they were being asked to fire thousands upon thousands of shells. Weird things started happening to them medically. They started reporting concussive-like symptoms, they started having nightmares. Just a whole lot of odd things that we didn’t think about then, but became an issue once we came back home.

I got out of the army in 2019 and was medically discharged, in part, due to what I now understand to be TBI symptoms from the concussive force of artillery. And then I started attending UNC-Chapel Hill in about 2020, 2021. I started doing research in military suicide and mental health, and that’s how I got onto this topic of blast overpressure injuries affecting the mental health of service members and causing the negative effects. In about December of 2022, one of my friends — Staff Sergeant Joshua James — died by suicide in Hickory, North Carolina. And he was another in a string of suicide and mental health issues that artillery men had. I reached out to The New York Times about his death, and that’s how I eventually became involved working on the story.

Stuckey: That is quite a journey there… I’m wondering, you mentioned this was something that you were observing while you were actually deployed. Was it something that you had kind of put together in a way that you considered reporting on at that time?

Johnson: No, at that point we had no idea what was going on. One of the weird things is that artillery [strategies], it was supposed to be safer than troops on the ground, i.e. Iraq [in] 2004, 2005, 2006. This is our way to support the Iraqi military without putting American troops at risk. But the symptoms the guys were reporting attend to what we understood to be PTSD symptoms, and we didn’t really understand what was going on. It was strange, but none of us really put the connection together with those symptoms and [artillery] blasts until much later when I started doing more research on the subject at UNC — and after, you know, more deaths and more mental health issues that people experienced.

Stuckey: That’s an unbelievable story. Obviously, we’re talking right now because of the Pulitzer Prize nomination — but you’ve kind of been in this world, reporting on this story and related stories for a while. Have things changed any in the past couple weeks?

Johnson: I would say, yes, in the past couple weeks [and] in the past year. The first article I wrote about it was for Slate Magazine [in] about April 2023. And even though blast overpressure has been talked about before, there wasn’t a lot of knowledge on the issue, right? I spoke to the [Department of Defense], I spoke to people I served with, and… people knew something was going on, but we didn’t understand [the origins]. Due to the past year reporting, working with the New York Times — I also wrote a New York Times opinion piece — we’ve seen massive movement in both awareness of the issue and institutional response.

Last month, Congress introduced the Blast Overpressure Safety Act that seeks to target a lot of the issues we talked about in our reporting. It is the most comprehensive bill on this issue ever — like, the previous few bills focused on blast overpressure injuries have been eight pages or 10 pages. This bill currently stands at 46 pages. So, that is one of the biggest things that’s come out of this reporting and one of the biggest things I’m happy about.

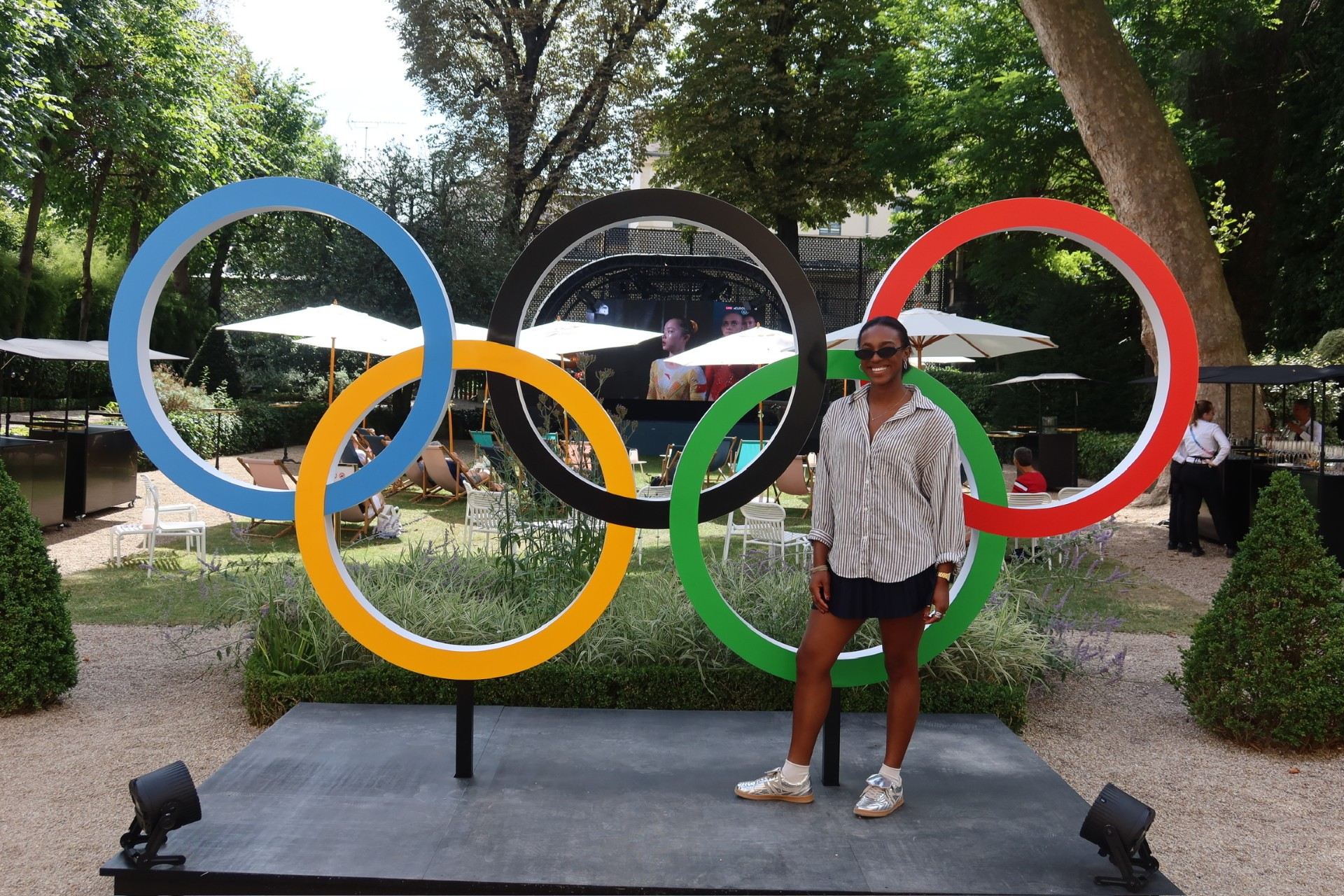

A photo taken by Daniel Johnson during an operation in northern Iraq in 2016. The long-range artillery gun, an M777, is similar to those featured in Johnson’s Pulitzer Prize finalist story examining traumatic brain injuries caused by repetitive artillery blasts. In this photo, the U.S Army soldiers are with Battery C, 1st Battalion, 320th Field Artillery Regiment, Task Force Strike. (Photo via Daniel Johnson)

Stuckey: How does that feel to have kind of a direct line between your reporting and then some actual action being taken at the federal level?

Johnson: It feels good, it feels amazing — because when I first started writing about the issue, I did a lot of it out of frustration. My friends were dying, people I knew were suffering. And then the question was, ‘Why?’ And then I asked myself, ‘Well, do people care?’ So it was an outlet. ‘Hey, if I write about this, maybe some people will pay attention. Maybe there’ll be movement on this issue within the next few years.’

But I’ve been really surprised and pleased at how massive the response has been. I wrote an article and then my mother would say, ‘Hey, have you heard about this blast overpressure issue?’ I’m like, ‘Yeah, mom, I wrote it.’ But just the fact that she knew about it and that other people knew about it, it’s great. Because one of the things when we write is that we hope it has an impact, we hope it has an effect. And with this issue, it has — and it makes me want to write more about the issue, especially because now we’re seeing changes. Of course, the changes won’t be instant, but we’re in a better place than we were when I first started working on this a year ago.

Stuckey: I mean, that seems like it’s sort of the dream when you get into journalism, right? It’s like, I’m going to do something that can actually affect a change. And I feel like it’s rare that you get to see it so directly happen. So, congratulations on that and on several fronts.

Kind of on the flip side of that, though: you’ve talked about how this isn’t just an interesting story for people to think about and take action on. This is something very personal that affects a lot of people. And for you, it affected a lot of your friends and you personally. Did that make it more difficult to do the work, or was that just an added motivation?

Johnson: For me, it was added motivation. A lot of soldiers when met them in Iraq, they were [in their] early twenties or still teenagers — and seeing how their lives have been affected even seven years later, it’s just tragic. Because I remember they gave a lot for their country, to do what their country asked them to do, and the least we can do is make sure they get medical care or get the treatment they deserve.

That’s been one of the biggest [reasons] why I’ve continued to write about the issue: what happened to us was wrong. What happened to me and my friends was awful. Hopefully we can prevent it from happening to the next generation of service members, young men and women who are joining the military now or tomorrow and will face a lot of the same risk. If we can reduce their exposure to blast overpressure, if we can ensure they have medical care, then that’s a win. You know, it doesn’t have to happen to them. That could happen to me, that could happen to my buddies.

Stuckey: What do you feel like is going to come next for you? You said you were motivated to write more on this topic, what do you think your next big project’s going to be?

Johnson: I think for this project, one of the things I’m really interested is military suicide, more broadly. The DOD is due to release a report on military suicide rates among certain jobs and military [positions] — like engineers, operators, stuff like that. Based on that data, I feel like my next work would be analyzing that and trying to see what the connections are between certain jobs and military suicide. With blast overpressure, I found DOD data that shows connection between jobs that are exposed to expulsions and higher suicide rates — and we’re talking about 40% higher suicide rates in some cases. That direct connection is big, because that’s going to play a key role in understanding what could be done to prevent military suicide or reduce risk. Especially when it comes to service members and minority groups, specialized job fields and so on.

Stuckey: We’re just about out of time, but I wanted to leave it open for you here at the end. If there’s anything else you wanted to mention that we haven’t gotten to yet?

Johnson: I would say, I know a lot of people who wonder [about] journalism in the current world. We talk about this information, misinformation… but writing can have an impact. I think that’s one thing: this process has taught me information can help. And that’s our job. You know, I say as journalists, or even because I teach, as teachers to inform people to make sure people have the best information available so they can hopefully make the right decisions. This whole process has made me hopeful for the future — whatever future work I do or other work people are doing.

Chapelboro.com does not charge subscription fees, and you can directly support our efforts in local journalism here. Want more of what you see on Chapelboro? Let us bring free local news and community information to you by signing up for our newsletter.