To comply with new regulations from the Environmental Protection Agency and better remove complex chemicals in its customers’ drinking water, the Orange Water and Sewer Agency is preparing to design and build a new $75 million facility at its water treatment campus in Carrboro. But while the project may ultimately help with its users’ health, it also will lead to noticeable rate increases in the short term.

OWASA officials held a presentation for local and state government elected officials on Friday, August 23 to share their initial research, rate projections, and plans to address per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances, also known as PFAS. A manufactured byproduct from items like non-stick pans, water-resistant or stain-resistant fabrics and cleaning supplies, PFAS are called “forever chemicals” because of their resiliency in the environment — often ending up in wastewater treatment, landfills, and nature after passing through carriers. Studies are still be conducted on the chemicals’ health impacts, but early research shows PFAS could contribute to increased risks of cancer, liver damage, immune system disorders, and pregnancy complications.

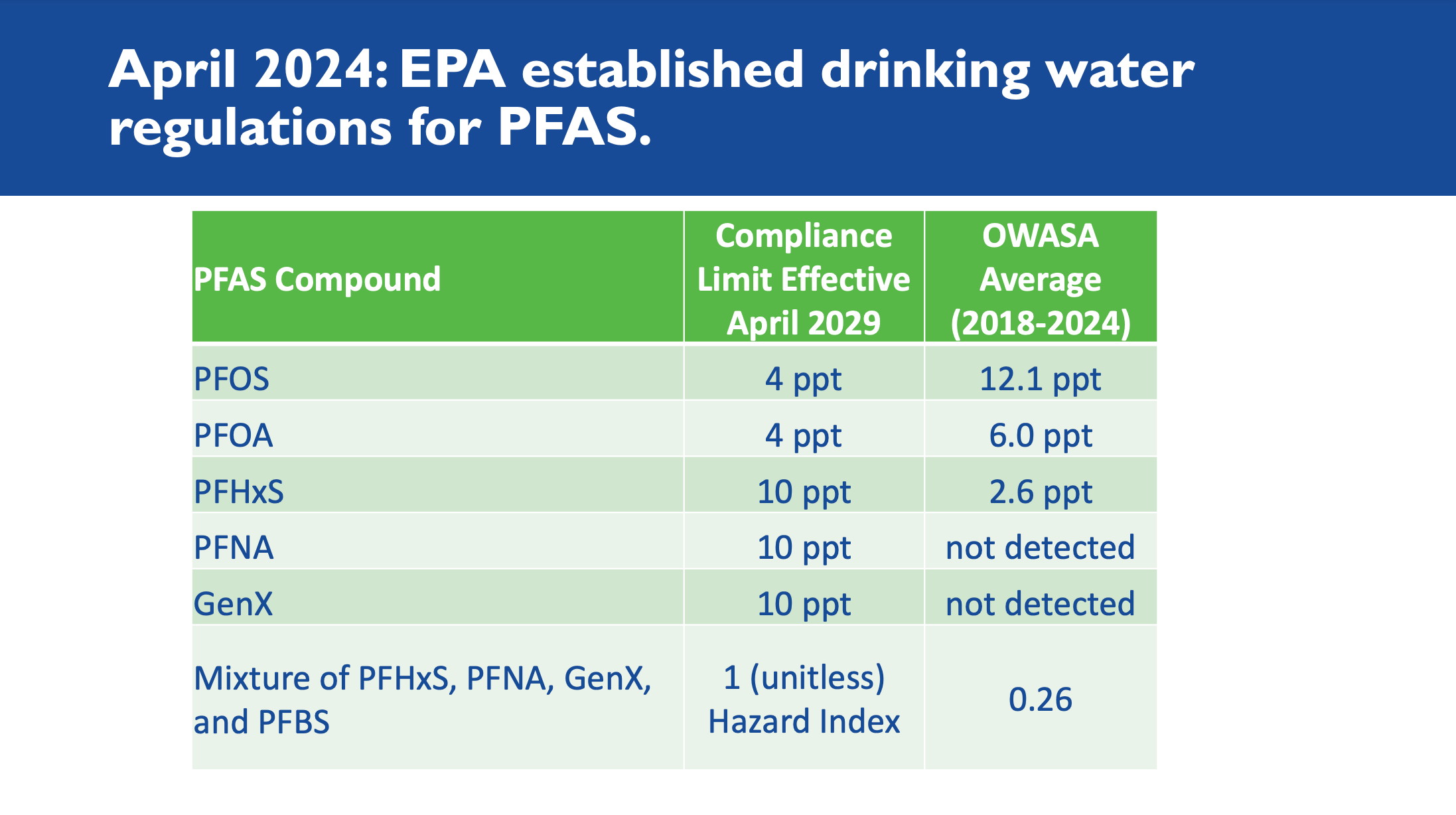

OWASA began monitoring its PFAS levels in 2018 after N.C. State and Duke published several studies the prevalence of the chemicals. But there was little to no guidance or regulation of the chemicals until the EPA finalized new regulations earlier this spring. All water utilities must comply with by April 2029, dropping the maximum amount to as low as 4 parts per trillion for chemicals like perfluorooctane sulfonate (PFOS) and perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA).

OWASA staff and its board of directors deliver a presentation to local elected officials on its plan to reduce PFAS levels on Friday, August 23.

The service agency for Chapel Hill and Carrboro communities is not immune to these chemicals entering its waters, with OWASA officials determining elevated levels of PFOA and PFOS come from the Cane Creek Reservoir — which is northwest to the towns and crosses into Alamance County. Despite being a protected watershed, OWASA’s researchers found areas within the watershed were used as “former biosolid application fields” until 2017, and a clear connection can be drawn between that practice and the PFAS levels.

While OWASA’s current practices include used powder-activated carbon to remove some PFAS from customers’ drinking water, the method falls short of reaching future regulation levels and still results in the chemicals being absorbed by the carbon and redistributed into products like fertilizer, mulch or lawn treatments.

During the presentation, Director of OWASA’s Engineering and Planning Vishnu Gangadharan said the new EPA regulations are meant to limit the presence of PFAS to the equivalent of three tablespoons of the compounds being in the 3-billion-gallon Cane Creek Reservoir.

“It kind of highlights,” he said of the analogy, “the risk that’s associated with these chemicals and how EPA is viewing that risk, and also there’s a challenge there with sampling techniques and treatment technologies to get it down to that small, low [amount] of concentration.”

And while the changes may mean less exposure of customers to those forever chemicals, the engineering director added each utility system will have their own way of addressing the issue since the best practices are still being developed.

“It’s the magnitude of this particular issue that seems so unique,” Gangadharan said. “It’s an issue that definitely is different than these others that I’ve encountered in my career.”

A slide from OWASA’s presentation, showing the new EPA regulations of certain PFAS and their average concentrations in OWASA’s water. (Photo via the Orange Water and Sewer Authority.)

An aerial of OWASA’s Jones Ferry Road treatment site, with an overlay of where the future PFAS treatment facility will be located. (Photo via the Orange Water and Sewer Authority.)

Presently, OWASA is researching the viability of two options that have shown improved reduction of PFAS: a granulated-activate carbon system, or GAC, and an ion exchange process. GAC — which is used by the Town of Pittsboro and reportedly leads to much improved results — absorbs the compounds through carbon and removes it entirely from the environmental cycle, while the ion exchange allows for more targeted elimination of harmful compounds at the expense of more physical waste and higher costs.

As testing continues, the utility agency will continue designing the future facility where all the equipment will go and water will go through the treatment to remove PFAS. Another goal of the project will be to “future proof” its design, according to Engineering Manager of Capital Projects Allison Spinelli, to allow for additional technology or methods to fit into the space and not lead to another round of major funding.

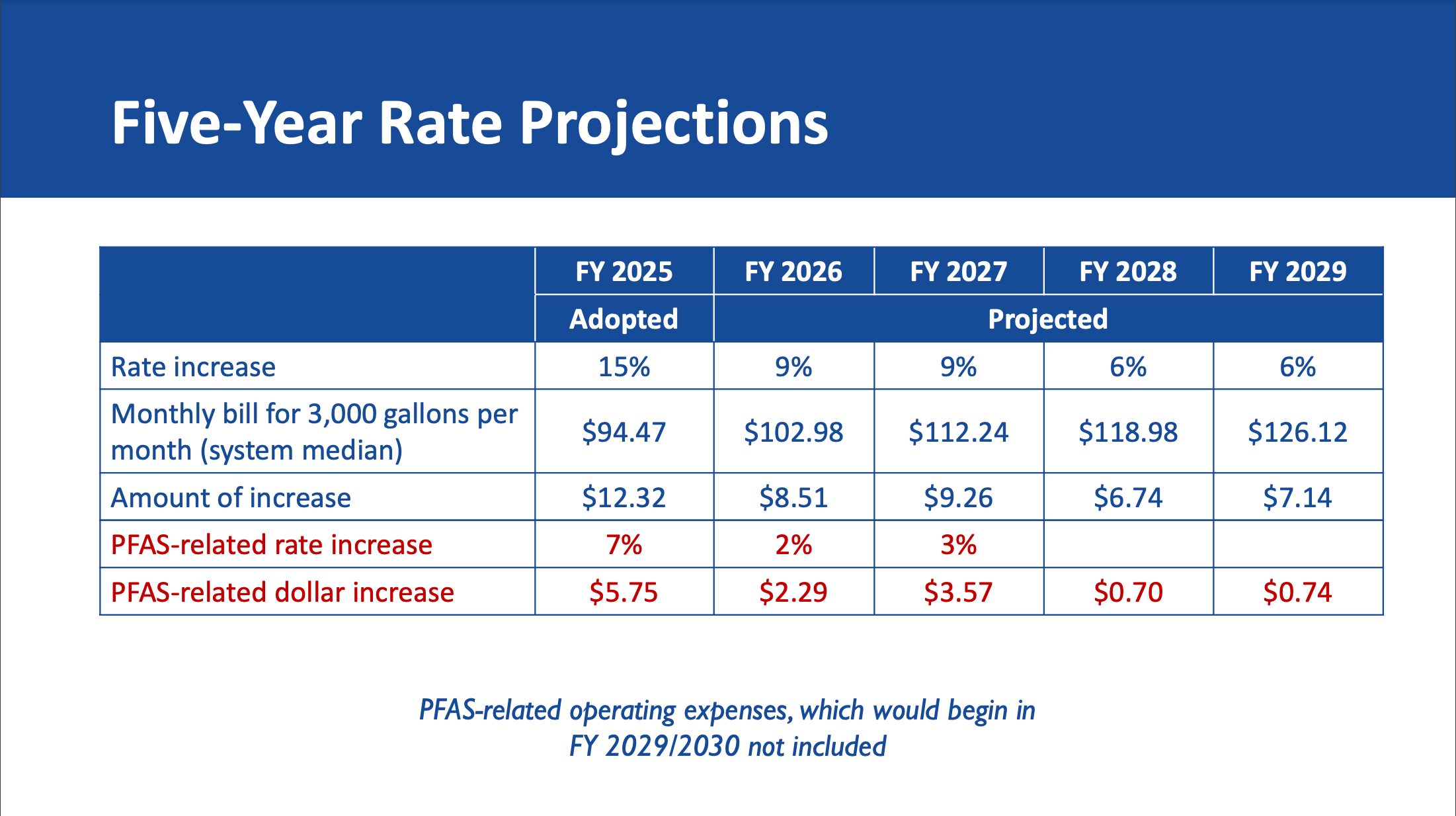

The cost to build this PFAS treatment facility and to purchase necessary equipment, though, is significant. OWASA receives about $55 million from its 86,300 customers each year, but the amount is almost entirely used to cover operating expenses and to stash for capital improvements. Since OWASA receives no tax subsidies or significant financial support from the local governments, much of the burden for funding these changes will be reflected in customers’ rates. The agency’s board of directors already approved a 15 percent rate increase for this current fiscal year, and annual raises of 6 to 9 percent are projected through the 2029 fiscal year in order to cover what OWASA will be spending on all capital improvement projects — which includes replacing aging infrastructure and not just the expansion for PFAS treatment.

A chart of the approve and projected rate increases for OWASA customers in the next five years, which includes how much is resulting from the PFAS treatment research and facility construction. (Photo via the Orange Water and Sewer Authority.)

OWASA officials said by joining a multi-jurisdictional lawsuit against the companies who manufactured and initial spread PFAS, they hope to be part of future settlements that could contribute funds to paying back for the PFAS facility construction. The agency is also examining federal grant options — but both of those methods are not expected to actually deliver money to OWASA for some time. In the short-term, their customers will be seeing steep changes in their bills and it will likely create an added importance for its “Care to Share” program, which uses overpays and customer donations to temporarily cover customers who have late bill payments.

Whether the local governments or state government can also contribute to help make up the funding long-term and level off the rate increases remains to be seen — but several elected officials in attendance voiced their concerns over how prevalent PFAS are and the expanse of the issue.

North Carolina Rep. Renée Price attended the meeting, since the Cane Creek Reservoir that serves OWASA and several of its customers are within her District 50 boundaries. She acknowledged the challenges high rates could bring to customers, but described OWASA’s plans as “impressive.”

“We’re talking about human health,” Price told 97.9 The Hill. “Yes, we’re talking about the process of filtering water, we’re talking about the price, we’re talking about budgeting and all of that. But at the end of the day, the concern and the reasons we’re doing this [are] because these forever chemicals affect our health, lifespan, and [create] other complications. How do you put a price on someone’s life or quality of life? Something has to be done.”

Price added she believes all stakeholders — including the state government and companies who put PFAS out into the environment — have a part to play in addressing the issue. That’s in part, she added, because the issue is so widespread and past the point of being able to point to one specific player responsible for the chemicals.

“We’re not talking about a single source point of pollution,” said Price. “We’ve got lands where biosolids were sprayed or applied years ago and they’re now getting into our water system. Yes, somebody needs to remediate or clean up some of these areas that we know are sources of pollution. But again, is it the only source — or is it multiple sources, and maybe we’ve only identified some?”

To learn more about OWASA’s current approach to addressing PFAS in drinking water and details on their aims to comply with upcoming regulations, visit the utility agency’s website.

Chapelboro.com does not charge subscription fees, and you can directly support our efforts in local journalism here. Want more of what you see on Chapelboro? Let us bring free local news and community information to you by signing up for our newsletter.