Local residents and many visitors to Chapel Hill and Carrboro know the towns have a reputation for downtown parking being difficult to find sometimes. While the local governments each have a new parking deck expected to come online later this year, it is not unusual to see people try to park at businesses and walk to different places instead of using public spaces.

With that premium on parking, though, comes an emphasis on towing in private spaces – and the operators contracted by businesses have built a reputation for being aggressive in how quickly they will remove vehicles. Every few years a new wave of dialogue begins after a driver is stranded, questioning whether the practices are predatory or how they are allowed, with the latest happening around Carr Mill Mall this past winter.

But this summer marks a historical turning point for what is and isn’t allowed in towing practices – as a state supreme court case involving Chapel Hill just passed its ten-year anniversary.

*******

With remote and mobile technology becoming more accessible in the early 2010s, Matt Sullivan remembers working as the staff legal advisor for the Town of Chapel Hill and dealing with towing complaints.

“What it was called back then… I was told one day, ‘Welcome to 21st century towing,'” says Sullivan, who still occasionally consults for the town government.

Operators and towing companies began using more cameras, mobile devices, and de facto command centers to closely monitor the lots of their business partners, spotting almost immediately when someone stopped patronizing where they parked and if they left. The result is what we see now: sometimes it’s just mere minutes between when a car is left unattended to when it is hooked up and taken away.

Sullivan says the practices sparked frustration when they first began because of the drivers not understanding the ability or aggressiveness of the towing companies. Since they are contracted to private lots, the tow operators are allowed to conduct their business in accordance with their agreement with the property owner.

But it was leading to safety problems. Sullivan says he remembers one instance where a tow operator moved too quickly to hook up a car and the vehicle flew off the handle going over train tracks in Carrboro. There was another instance where a dog left in a car was taken to the tow storage facility. Fights between drivers and operators began to happen more frequently.

“It was getting dangerous,” Sullivan says. “There was gun-pointing, there were punches thrown…so, 21st century towing was creating multiple dimensions of problems.”

Much of the drivers’ frustration stemmed from the hurdles they faced in order to retrieve their vehicles. To this day, most operators require cash payments and charge an additional fee for using credit cards – which sometimes are $100 or more. A lack of signage around a lot or explanation of the camera system left others to believe their car had been stolen.

Chapel Hill Town Manager Chris Blue, who worked at the town’s police department for many decades, says officers would regularly have to explain the towing culture and would have to relay information to the drivers.

“Also, a number of the storage lots where the vehicles were towed were well outside of the city limits,” Blue says. “That created a couple of problems – one, actually getting there to retrieve your vehicle. But also… sometimes it felt unsafe for folks to go out to the middle of nowhere where there’s a storage lot, it’s dark and an unfamiliar area, perhaps – with $200 or more in your pocket.

“So,” he continues, “those were the concerns we heard over and over and over again: this uncertainty about cost, the location of storage facilities, and the credit card issue.”

A sign for the Carr Mill Mall, whose strict towing enforcement has led the Town of Carrboro to warn drivers to park elsewhere when visiting downtown. People who unlawfully parked and been towed report being charged significant convenience fees and having to leave town to retrieve their cars.

In 2012, the Chapel Hill Town Council decided to try and make a change. Sullivan was tasked with working alongside town staff to craft an updated towing ordinance – which many towns have – to set a standard for what people could expect if they park unlawfully and are towed. That included a maximum towing fee that could be charged, alongside no requirement for cash payments and a minimum sizing for signs to alert patrons of business’ towing agreements with operators. The town aimed to strike a better balance of towing companies being responsive to calls if their storage facilities for cars were farther away from downtown, requiring a call to be returned in 30 minutes once someone requested the location of their car.

Blue says he believes those updates aligned with the town’s values of promoting a welcoming space for any visitors while being receptive to the towing operators’ business practices.

“I think the idea that the town was trying to address something that had become a negative talking point about visiting our community and certainly having an impact on our local economy and vibrancy downtown,” the former police chief says. “So, all in all, I think these were responsive, reasonable, and generally well-received changes at the time.”

******

Aligned with the towing changes, though, was another detail: the use of cell phones. The Chapel Hill Town Council saw the update as a chance to limit how much drivers were on phones while behind the wheel – which ended up playing a part in how the changes came undone.

It did not take long for the ordinance to come under fire, as George King of George’s Towing and Recovery sued the town over its changes to the towing ordinance. He argued not only did the new fee limit prevent him from covering operating costs, but the mobile phone element conflicted with the tow operators’ ability to do their jobs. If the tow companies were meant to monitor the spaces in an efficient, timely way – while staying available to people who may call about having been towed – they would violate the ordinance and be unable to provide their contracted services.

Sullivan, meanwhile, argued alongside the town attorney Ralph Karpinos the ordinance was necessary over the concerns that arose from the practices and the measures were within the town’s rights to protect its residents from harm.

“I think we made a strong case to say, ‘We need something to keep people safe,’” he says.

Ultimately — on June 12, 2014 — the state supreme court sided unanimously with King. The justices said the Town of Chapel Hill overreached its governance as a municipality to curb phone usage, which was stricter than the state’s laws at the time. Additionally, the court warned against “unfettered power” that would come from towns implementing a price control of any kind on an industry. The ruling meant in addition to the mobile phone piece being struck down, the maximum towing fees and requirement for credit card payment were also removed.

“While Chapel Hill has the general authority to regulate towing,” wrote Justice Paul Newby, “by capping fees, the town inappropriately places the burden of increased costs incident to the regulation solely on towing companies. Accordingly, we hold that Chapel Hill exceeded its authority by imposing a fee schedule for nonconsensual towing from private lots.”

According to Sullivan, the ruling further cemented that any chances to the towing industry to change those practices would have to come from the state level. And this summer, a representative for Chapel Hill and Carrboro tried to do just that.

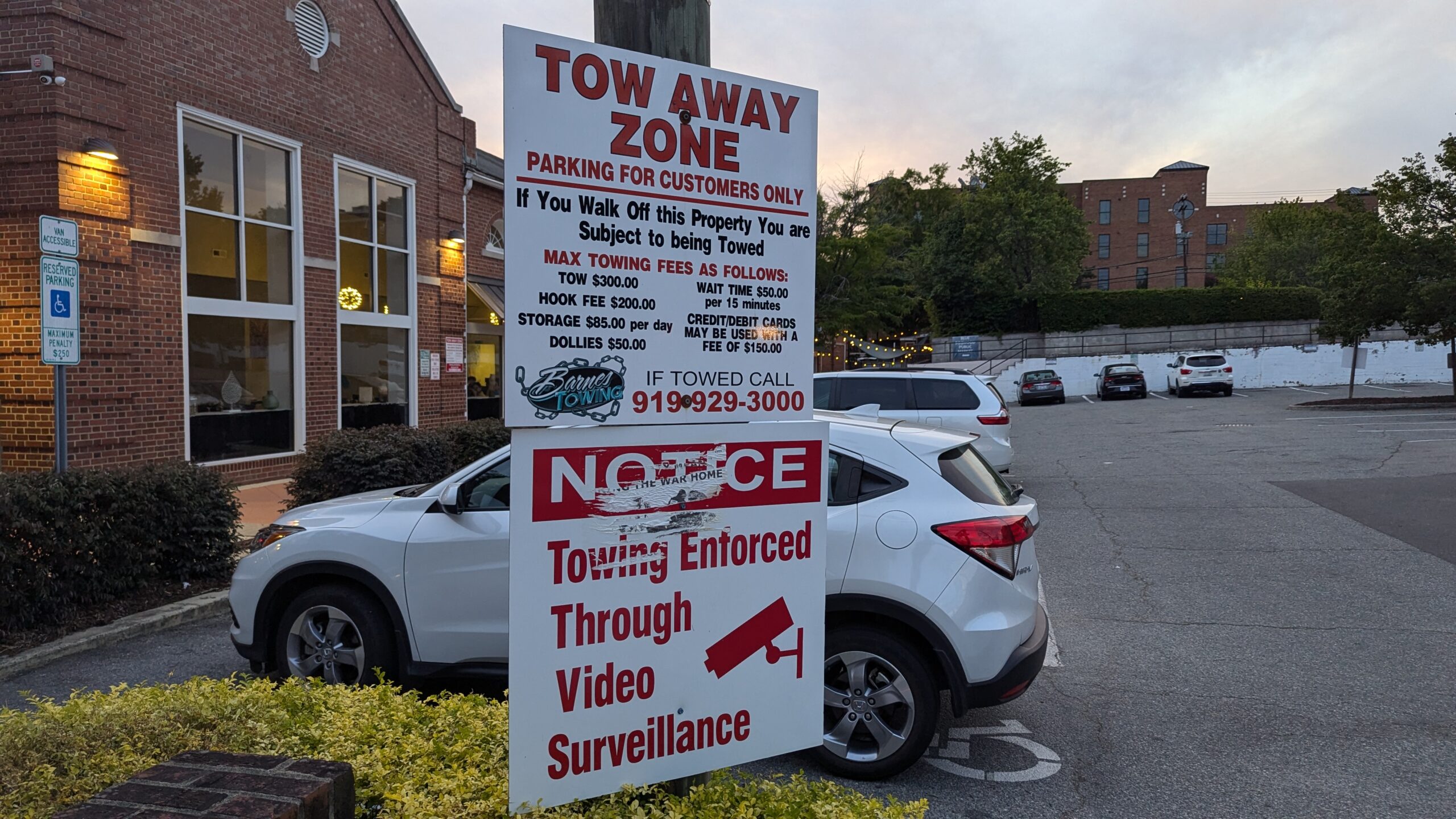

A towing sign in Chapel Hill at 306 West Franklin Street. Creating a minimum size for signs in lots enforced by towing operating was one of the few updates from 2012 the North Carolina Supreme Court allowed to remain in the town’s towing ordinance.

******

Rep. Allen Buansi says after hearing of stories from constituents about the latest rounds of aggressive towing strategies, he felt compelled to team up with lawmakers from districts in Wake County and sponsor a bill. The measure proposed a limit on connivence fees when using a credit card to pay for towing fees — and requiring that option be made available. Buansi says it was stories of hearing constituents pay significant prices because they did not have cash that spurred his interest in change.

“It creates a situation where a person doesn’t really have anywhere to go when they’re being unfairly treated or targeted,” the District 56 representative adds.

Another aspect of the bill is ensuring those whose vehicles are towed are not charged for the storage of their cars on days where the towing company is not open, which Buansi said may happen on holidays or weekends. The key detail, though, is that regulation of the towing practices and fees would be moved under the North Carolina Attorney General’s Office. The office is already where more than four dozen complaints about predatory towing were sent in the last year, says Buansi, and has a track record of preventing North Carolinians from being taken advantage of through its Consumer Protection Division.

“We thought, because of the history it has of handling consumer protection complaints,” he says, “the attorney general’s office is the best place to empower with some regulation over predatory towing.”

The bill was not taken up during the short session of the North Carolina General Assembly that ended in June, which means it will need to be brought forward again next year. Buansi does not rule out that happening, especially with as many sponsors as the measure received.

Sullivan says he thinks the proposal is relatively sound, based on the supreme court’s ruling from a decade ago.

“Maybe there is a parallel,” he says. “At what point are you price gouging with a tow fee?

“The other side would argue,” Sullivan adds, “’Well you really aren’t [price gouging.] We’re trying to do a deterrent [method] and if we raise the money to a certain level, people are just going to stop doing it.’ I get that argument too.”

Until then, the simplest advice offered by both the towns of Chapel Hill and Carrboro is to ensure you use public parking spots whenever possible and being aware what qualifies as a private lot. Several hundred new town-owned spaces will soon be available at both East Rosemary Street in Chapel Hill and South Greensboro Street in Carrboro, and both local governments have emphasized way-finding efforts to the existing lots.

Blue adds that when it comes to the frustration around the towing practices, it’s difficult to not escalate the situation. But he recalls being towed himself while a student at UNC — when he parked in a private space in downtown to try and quickly pick up food, and his car was gone when he returned a few minutes later.

“I remember that feeling of being angry at the tow company, and being angry at the business that got my car towed,” he says, “but ultimately concluded that I parked right under the sign that said I shouldn’t have parked here. And so, I had eat crow and go down to pay $75 — which, at the time, was a lot of money to me — to get my car back.

“All of these actors come together in this formula and it is a tough situation,” Blue concludes. “I understand the interest in wanting to regulate it, but it is a complicated conversation.”

King was reached by Chapelboro while reporting this piece. At the time of publication, he said he did not wish to provide any comment on the case or its anniversary.

Chapelboro.com does not charge subscription fees, and you can directly support our efforts in local journalism here. Want more of what you see on Chapelboro? Let us bring free local news and community information to you by signing up for our newsletter.