Art Chansky’s Sports Notebook is presented by The Casual Pint. YOUR place for delicious pub food paired with local beer. Choose among 35 rotating taps and 200+ beers in the cooler.

Name-Image-Likeness is exactly where we thought it would be.

When the California legislature passed the first NIL law in September of 2019, few major colleges knew exactly what to make of it. But since the NCAA backed away with some guidelines but little guidance, schools took it upon themselves to interpret the rules as they wanted, and so far nobody has told any school that what it’s doing is wrong. So the beat goes on.

The knee-jerk reactions were phrases like “out of control” and “wild west” and the “rich will get richer.” So far, some of all that has become true.

There were supposed to be two steadfast rules about NIL. One was that it could not be “pay for play,” meaning coaches and schools could not promise recruits money if they signed letters of intent or transferred in. The other was that employees of athletic departments were to have nothing to do with NIL.

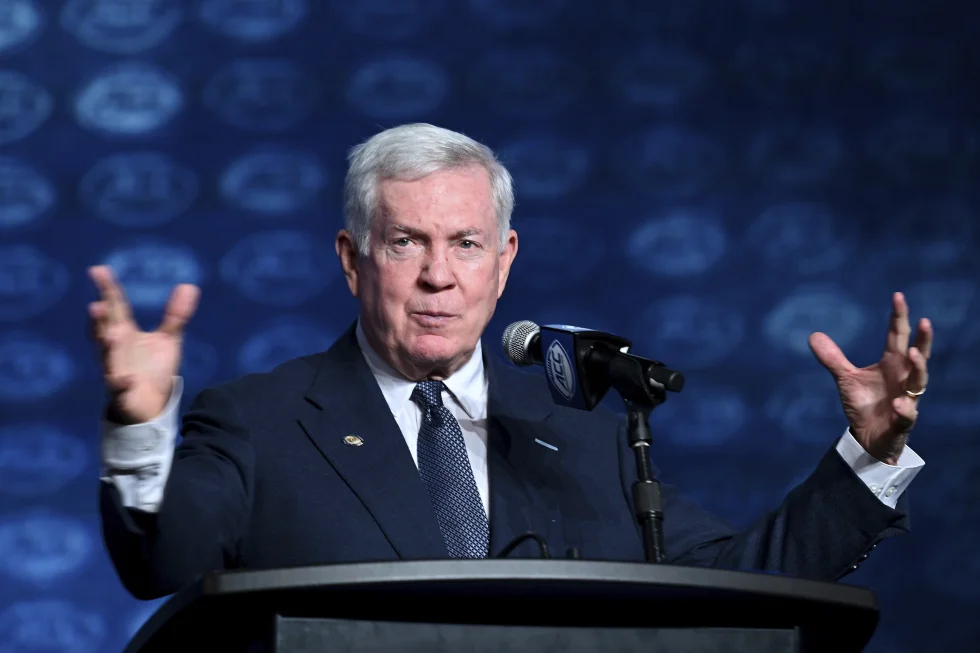

Some coaches, Mack Brown among them, have said it is clearly pay for play because recruits are being told dollar figures for what their NIL rights would bring with little talk of how they would earn the money. “It was an illegal inducement before NIL and it still is,” Brown said. “Cheaters will still cheat.”

UNC’s athletic compliance office vets proposals from companies or agents, and it is still the only way NIL deals can get it done at Carolina. We’ve heard wild stories about other schools offering millions in NIL money to coveted athletes and heard enough examples to believe the wild west is alive.

No matter how they raise the money to support NIL deals, the biggest football schools with the richest and most passionate donors are going to wind up with the best players and teams, like they always have. But NIL, along with the transfer portal, has sent that process into overdrive.

How can a coach tell a recruit how much money the last player in his position on the field or the court was making and “you could make that, too.” Alabama supposedly told Jarin Stevenson what Brandon Miller was making, implying that the Pittsboro product who reclassified could make that too.

Except Miller was a freshman sensation and wound up as the second pick in the June NBA Draft, which is an impossibility for Stevenson. It is apparently no one’s job to check all that out, so every school can claim it is doing it right.

Carolina tells recruits about its NIL program and how athletes who come would be exposed to it, but that’s all. And many families believe that their kids’ education and “40-Year Commitment” will be more of a factor in the long run.

But it’s like anything else these days, say it enough times and people will buy it. Even if the sales are being made without any rules or true oversight.

Photo via AP Photo/Brynn Anderson.

Chapelboro.com does not charge subscription fees, and you can directly support our efforts in local journalism here. Want more of what you see on Chapelboro? Let us bring free local news and community information to you by signing up for our biweekly newsletter.

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: RSS