Well, how about autumn 2025? If you’ve been outside anywhere with more than a tree or two and taken a moment to look up or out, you’ll no doubt have noticed the jumbo-sized crayon box of color that was playing out all over the place. Here’s a handful of frozen moments in the lives of some of my workmates. I know it’s not a pumpkin-flavored whatever, but I trust it will carry you and yours along with me and mine into the waning light, crunchy footfalls and all-too-short days that precede the wondrous wintry gloom. Every season transits into the next, but fall, to me, seems too brief. It’s not just a merge lane for the holiday freeway.

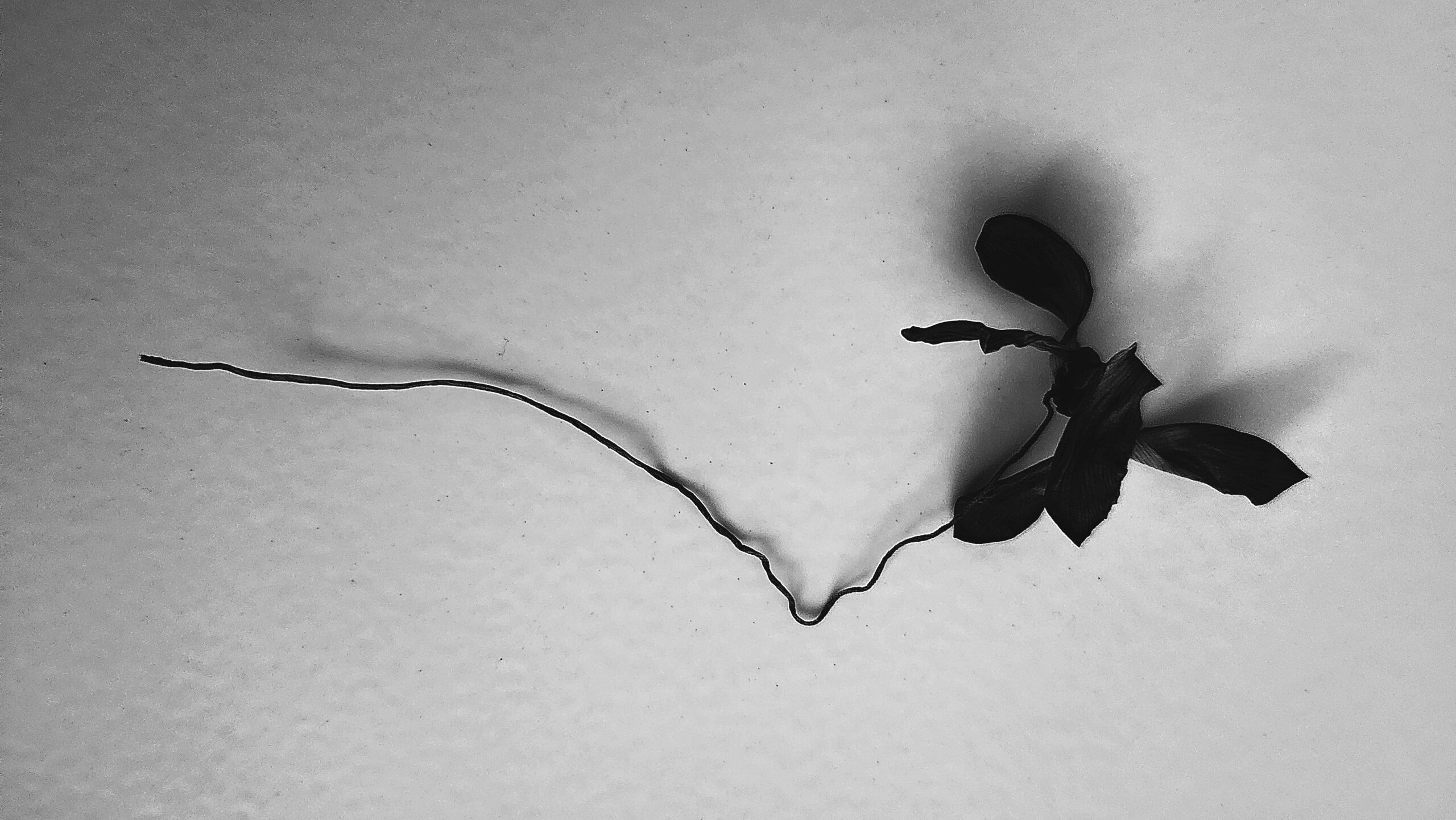

- Magnolia macrophylla (Bigleaf magnolia)

- Acer campestre (Hedge maple)

- Acer palmatum ‘Palmatifidum’ (Palmatifidum Japanese maple)

- Fagus grandifolia (American beech)

At the risk of being predictable, we thought it only proper and fair to conclude our first year of articles with a brief visit to that most seasonally appropriate of plants: holly. And Margot will share some nifty ideas on what good may arise from the swirling mess of invasive autumn olive that lurks and looms on the edges of her domestic domain and yours, too, most likely.

Take a Bough

I love a good holly tree. Especially as the woods around me begin to senesce and undress (as is their autumnal wont), I find some comfort in the echo of summer that the splashes of green convey. The American hollies (Ilex opaca) that naturally and effortlessly dot the untended ground around us are welcome winter companions.

A saunter across the northern ends of the University will allow one (if paying attention) to meet many exemplary specimens of the genus Ilex.

(In fact, look for my winter walk through campus, a 3-hour stroll highlighting some of my favorite plants and fun facts around the buildings that also inhabit this place. Yep, that was a commercial. It just slipped out. Details in our next installment.)

As the University and its appended village slowly grew, care was taken with the trees. That continues into the twenty-first century at the hands of many talented plantsfolk over the last several generations. Their legacy remains; Carolina is a treat to walk. The Arboretum is a straight-up unicorn, 5 acres of undeveloped (building-free) land in the middle of a large R1 research institution? Awesome. Magical. All the superlatives.

Carolina’s hollies are, for the most part, recent additions. UNC hired Francis LeClair as a landscape worker back in 1935. This Belgian emigre was promoted to Director of Grounds in 1953, serving until his retirement in 1959. He was an avid collector and grower of hollies, caring for 120 different kinds and planting them with cheerful abandon all over the place. One encounters many when moving through the older parts of campus — McCorkle Place, Polk Place, Coker Arboretum, Chapel Hill Cemetery.

These originals stood here long before the first cornerstone was laid, when this place was a quiet forest with a small chapel at its edge and a handful of unincorporated North Carolinians making their way through the latter days of the eighteenth century. One of the last forest remnant hollies in McCorkle Place was removed a couple of years ago — it was in decline and posed a significant risk to passers-by.

Until recently, there were scads of Burford hollies (Ilex cornuta ‘Burfordii’) flanking Old East and Old West dormitories just north of South Building. These were removed a couple of years ago, and rightly so, if I may opine. I’ll warrant that this is the plant many of you folks may see when you close your eyes and someone says “Christmas Holly” out loud. Glossy green slightly incurved leaves with a single spiny tip, bright red berries in clusters along stout grey stems. Likely sheared into a sausage roll if in a line, individual meatballs if on their own, sometimes elongating into SoftServe conical dollops if a shearing cycle got missed the previous year. They are ubiquitous, boring and (no offense to the flavor) vanilla.

Meet UNC’s holly trees

The holly in the photo below is a lovely example that sits in back of Caldwell Hall. The fruits will remain until some whisper alerts the robins that all is ripe with the world and they will then descend upon the tree and feast.

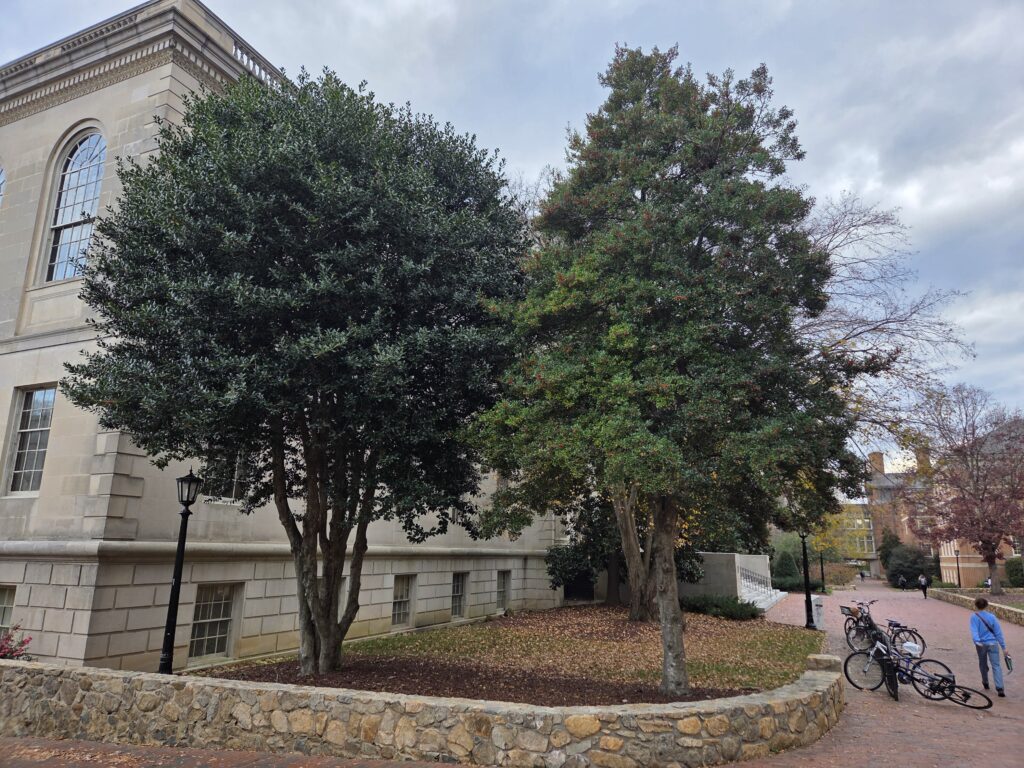

An exemplary holly behind Caldwell Hall

This American holly — next picture, please — is a particular favorite of mine as it is practicing canopy sharing with the happy and healthy white oak (Quercus alba) growing alongside.

A Quercus alba (white oak) and an Ilex opaca (American holly) dance a pas de deux on Old Campus.

In truth, the holly was planted too close to the oak, considering the ultimate size each of these plants will achieve. In this case, this observation can move quietly to the back of the room and have a quick nap, since the holly has charted a swervy trajectory, extending up and away from the twiggy extremities of its neighbor. It still kinda blows my brain up a little bit every time I walk by and I point it out to folks who happen to be with me. These trees sit between my workplace and excellent coffee, and since I happen to hold sacred the small snippet of time labeled “coffee break”, that forms a significant paragraph in the narrative of my day.

This lusterleaf holly (Ilex latifolia) is likely the largest of its kind in the country. That’s right, a National Champion, right here at UNC, what are the odds?!

Ilex latifolia (lusterleaf holly) at Carroll Hall

As the folks who run the whole National Champion Tree Program only keep a registry for trees native to the U.S., we may never know for sure. But according to Dr. Michael Dirr (professor emeritus, University of Georgia, who literally wrote the book on the subject … it’s called the Manual of Woody Landscape Plants, in its 6th edition now, I believe), it’s a solid candidate.

Here are two more gems:

Ilex ’Nellie R Stevens’ and Ilex x attenuata ‘Foster’s #2’ at the NE corner of Wilson Library

Ilex decidua (possumhaw) behind Hamilton Hall

This last picture, from the southeast corner of Gardner Hall, shows off the variety of holly structure and texture.

Assorted hollyness at Gardner Hall

These are plants that are lovingly coaxed into all manner of forms. Oftimes, the tool of choice is a hedge trimmer (yuck … sorry, did I say that out loud?); in a less fractured time, limbs and twigs were snipped individually, caution and care informing the craft. Don’t get me wrong, I’m a fan of using the right tool for the job. I would argue, however, that the right tool would never coarsely tear at what could and should be cleanly sliced. Yes, it takes time, and yes, it requires some training, skill and — vitally — patience, but the results speak for themselves. If one is listening.

Perhaps on that note I should yield the page to Margot. She’s got some excellent craft to convey.

Decorate for the holidays with invasives

If you’re looking for some natural decor this holiday season, you can always rely on the hollies, magnolias and pines to zhuzh up your place. But what if I told you you could make decorations and do some invasive removal at the same time?! It’s true.

The most obvious candidates are also the most prevalent: The various forms of privet and elaeagnus. They make great wreaths that are every bit as good as the grapevine ones from the store and the price sure is right.

Invasive plants to use for holiday wreaths

There are several species of elaeagnus and all of them are invasive. The plants dominating my property line are autumn olive/spring silverberry (Elaeagnus umbellata). They form dense thickets that crowd out native species. The birds and other wildlife do like the seeds, but that also makes it spread like crazy. The deer are utterly uninterested in its greenery. The stand at my place has been bugging me for years, but my previous neighbor had no interest in getting rid of it. Thankfully, my current neighbor has agreed that this is the year we’re going to start pruning it out, just in time for making wreaths!

And do we need to talk more about privet? Again, a few kinds, all of them happy to take over. My neighborhood has a lot of Chinese privet (Ligustrum sinense). While I’ve gotten rid of most of it at my place, my other next-door neighbor is less vigilant and has a big one that hangs over the fence into my backyard. Every holiday season, I get out my Mom’s trusty loppers, whack the intruders and make stuff.

Margot’s Mom’s trusty loppers still make the cut.

How to make a wreath with invasive plants

- Cut a bunch of longish shoots or whips.

- Strip/snip off the leaves if you want a bare wreath or plan to soak the material overnight. Note: The stalks are plenty pliable if you use them shortly after cutting.

- Make a circle at the thickest end. Pro tip: Use floral wire to secure your circle if you, like me, have arthritis and your grip isn’t what it used to be.

- Weave the skinny end through, under and over all around the circle.

- Tuck the end in to finish off. Note: Tuck in another whip or shoot and repeat the process if you want a chonkier wreath.

- Secure the wreath with more floral wire needed.

- Cut and loop ribbon or landscape twine for a hanger.

Elaeagnus umbellata (Autumn olive/spring silverberry) makes a pretty wreath with leaves on or off.

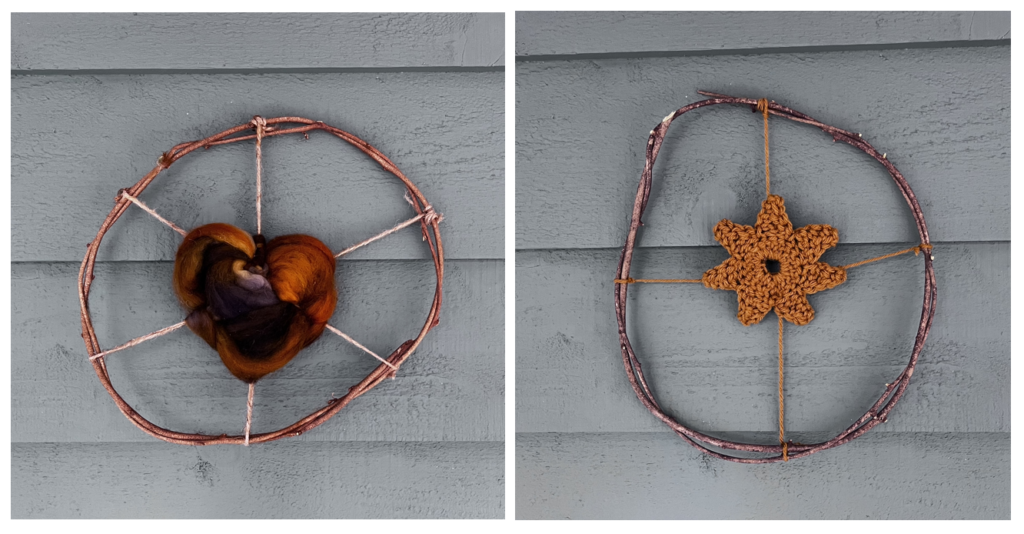

Feeling a little craftier? Me, too. This year, I experimented with wool. I crocheted a sun for a privet wreath and made a sort-of suncatcher using roving (my new favorite craft material) with some landscape twine and elaeagnus. Of course, if ribbons and bows and ornaments are your thing, go for it!

Not every wreath needs a bow.

NB: If you’re using yarns and other materials for wreaths you’ll hang outside, make sure they’re safe for birds and critters that like to build nests.

Bonus decor!

Maybe you just need to get that hot glue gun going (I recommend the Chandler, myself). I’ve got you. Head out to find some sticks and twigs. Bonus points if you can find a few sporting some lichen. People make a boatload of things with this material (trust me, you could lose hours scoping out Instagram reels). My favorite, probably because they’re less fussy, is a star. Here’s how:

- Get sticks in sets of 5.

- Cut your twigs to about the same length.

- Fire up your glue gun.

- Try different configurations while the glue gun’s heating up. Pro tip: Snap a pic once you get an arrangement you like so you don’t forget it.

- Get to gluing! Caution: It really is hot! And gluey. Be careful.

- Press contact points while the glue sets up.

- Let dry completely.

- Cut and loop ribbon or landscape twine for a hanger.

I made what seemed like a metric ton of these a few seasons ago and have them all over my house. They’re sturdy enough for outside, too, but the glue will fail after a bit.

Twig stars are nice year-round.

If you try any of these ideas, post them to your socials, use the #refugium hashtag and @ me on Instagram or Threads.

Happy holidays!

(All campus photos by Geoffrey Neal. Crafting photos by Margot Lester)

Geoffrey Neal is the director of the Cullowhee Native Plant Conference. See more of his photography at soapyair.com, @soapyair and @gffry. Margot Lester is a certified interpretive naturalist and professional writer and editor. Read more of her work at The Word Factory.

About the name: A refugium (ri-fyü-jē-em) is a safe space, a place to shelter, and – more formally – an area in which a population of organisms can survive through a period of unfavorable conditions or crisis. We intend this column to inspire you to seek inspiration and refuge in nature, particularly at the Arboretum!