There was this summer where I kind of lost my mind with regard to matters practical, tasks in the oval labeled “you got this,” options for the consumption of time and all things worth doing with eyes open. I signed up for some classes at UNC. Lots of classes. My crash landing in the fluffy field of biology. Boom. Intro to Bio and Principles of Ecology that first summer, more time in the lab than at my job.

The reward for all that prep came in the form of Local Flora and Plant Taxonomy, two unassuming courses taught over in Coker Hall. I was fortunate enough to study with Dr. Jim Massey, then curator of the UNC Herbarium, grower of superlative daylilies and collector of folk art way before it was hip to even consider that as a thing, back in the fading light of the 20th century. These were great courses taught by an enthusiastic, engaged and thoroughly interesting human. These excellent courses set me firmly into contact with the soil that would grow my sometimes interest into a full-out career. I continued with coursework at UNC, eventually taking both courses a second time under Dr. Massey’s successor, Dr. Alan Weakley, arguably the hardest-working and most deeply talented botanist in the Southeastern United States today. No idle flattery, just honest opinion from someone who gets/got to be there.

So, you say, what? Well, the superpower that was revealed to me in those unassuming classrooms under those unflattering fluorescents was that I could learn the names of those plants! How about that? And that carried me away from a perfectly serviceable float through pools of low-wage, high-stress average into more interesting and, frankly, above-average swirls and eddies, even the occasional rill. I became a plant person.

Chestnut oak twig

I’m a plant person now

Now I find myself meeting new friends everywhere I go, recognizing familiar forms. There is a tremendous comfort in that, in the knowing. A world replete with a crayon box full of colors but lacking identity suddenly opening up to me in a new way. I learned the names of some of my fellow guests — familiar heads, shoulders, knees and toes that have been in the same party with me for decades. A myopia clearing. Pretty neat. A little study, some observation, and careful use of the tools at hand. That’s where I find myself now, sauntering with similarly curious folks through the woods on a Sunday afternoon, looking at the trees.

The tools I started out with were simple, accessible, though sometimes clumsy. Books.

I’ll try not to sound like that old guy who goes on about how it was different (implying better) ‘back in the day.’ Frankly, I find that a bit annoying, and fortunately, I recognize the impulse when it comes up in me enough to change my voice into some silly semblance of a cartoon character I once emulated in front of the TV on a Saturday morning before I deliver my lines. Somehow that makes it less ridiculous. We get it, old dude, let’s move on.

“the only guest list available at the time”

But the books were the story just a little while ago. Pre-internet, pre-app, pre-historic. We hauled around a copy of The Manual of the Vascular Flora of the Carolinas, copyright 1968, by Radford, Ahles & Bell. A boring green cloth board cover and print that my younger eyes could read without difficulty. Now we squint. 1,245 pages, 3 ½ pounds, 3,200 plants and not a photograph to be found. It was the only guest list available at the time for what I was to discover was, and still is, the most interesting party I’ve ever attended. A quick tour of the first few pages and some basic rules and I was on my way.

And I was on my way

Maybe a bit long-winded in the way of introductions to the splendor and wonder that is ‘How to Know the Trees’ in its basic state. I went this route not to tire you or (worse) bore you, rather I decided this would be a petite salade before the heartier fare. Much of what I do involves knowing something about the plants around me; much of what we do as gardeners relies heavily on knowing something about all sorts of plants, those that are here/now and those that might someday be here/now. Knowing a bit about how to know seemed to me to be a subject fit for discussion. So there.

Crackle and spark

My most recent opportunity to speak to the trees came just a couple of weeks back when I was afforded an opportunity to walk with a group of folks through the woods at Bluestem Conservation Cemetery.* Margot has been helping out over that way for a while, and the location came up in conversation last year as we were discussing places to take a group out for a walk to look at trees.

I have been giving tours of the Coker Arboretum for a while and have even led a campus walk in winter once or twice, continuing in the steps taken by William Lanier Hunt and Ken Moore. Those gentlemen buoyed me along my way by example and enthusiastic encouragement. (Even before I settled into this plant-centered life, I would encounter Mr. Hunt as he was a regular guest at a restaurant I worked at on W. Franklin St. He was dapper–no, too flippant a word–smart, confident in bow tie and jacket. Always a polite word and, when he had a longer moment to spare, some comment on the quality of the landscape plantings surrounding my place of employ. Nothing mean-spirited, merely opinions offered up in passing time. Delightful.)

Bluestem winter tree ID walk (Photo by Margot Lester)

Back to Bluestem…this was our second walk through this special ground. The first was a winter tree walk accomplished last February. I appreciate being able to move through landscapes at different times of the year and over the years. Gardens, woodlands, fields, meadows, pastures, flats, fens, scapes, balds and hollows are all evolving entities. They move and breathe and shrink and swell and color and drain and speak in a panoply of languages and gestures. Life’s rich pageant if there ever was one. I prefer being outside because there’s just so much more to absorb; I might not actually understand much, but at least I’m in it. And learning a bit about the plants around me only brightens the moment. How much better the foreign film with subtitles than without.

We are surrounded by so much language/music that we will never understand. The crackle and spark of a crisp morning just after sunrise and the shapes emerge and gain definition. The first sketch of trees where just a little while ago there was dark nothing, that’s a perfect start to my workday. A blend of earnest preparation and blind fortune has placed me at the edge of a garden. Twenty-five years ago, it was all a smeared field of greens with the occasional flowery dots of yellows and reds. Pretty, unknown, a wrapped confection. It was a party invite and, even with the mosquitoes, has proven to be a pretty fun gig.

Guidebooks to the trees

So if you’re just arriving and would like a place to start, I might suggest a couple of less weighty texts. Smaller books that can live in your glovebox, or in your daypack, or on a desk or shelf somewhere handy.

“delightfully portable”

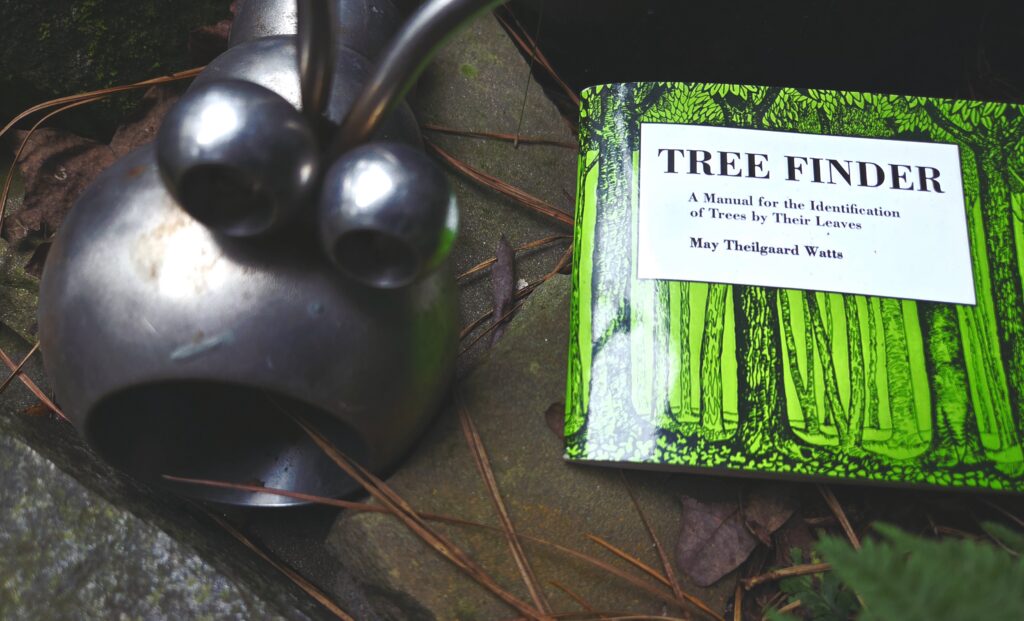

The first is the delightfully portable Tree Finder, A Manual for the Identification of Trees by Their Leaves, by May Thielgaard Watts, c. 1963. 60 pages, about the size of a cellphone, just right for a shirt pocket. This little giant booklet will cheerfully and painlessly guide you towards recognition of approximately 150 different species of trees. That’s not a typo, it’s chock full o’ trees! The area of coverage extends nearly to the Rockies, so there’s some trees in here that you’ll not encounter on your next woodland walk in central North Carolina, but that works just fine as Ms. Watts includes small range maps alongside each entry to help you sort out who lives where. A few nonnative species are thrown in for good measure, a common addition in many plant books, as it’s always wise to learn a bit about the uninvited guests as well as the invited ones. One of the best features of this book is the distinct absence of botanical jargon.

Many plant ID books are penned with an attached glossary that absolutely has to be consulted (distressingly often) just to translate the descriptive text. Here, a leaf is a leaf, hairs are hairs, and when a “stipule” is mentioned, care is taken to say where on the plant that thing occurs and what it might look like. So helpful! This is such a great basic field book, I make sure all the students in my plant ID class get a copy. There is even an edition that focuses on identifying trees in winter (Winter Tree Finder, in case you were curious), a topic for later discussion.

“a paperback gem”

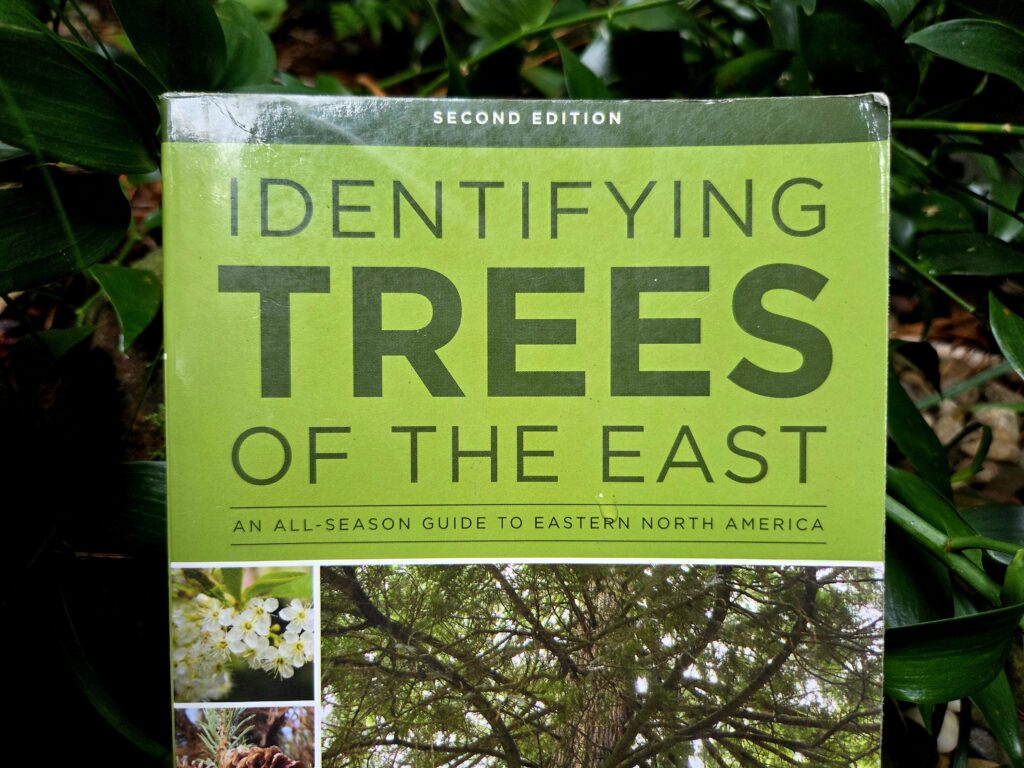

When more info is needed, or when the desire to acquire another book can no longer be ignored, then the next title I recommend would be Identifying Trees of the East, An All-Season Guide to Eastern North America, by Michael D. Williams, c. 2017 (now in its 2nd edition). This paperback gem is a definite upgrade. It’s got color pictures and way more information, starting with the basics of leaf identification. Are the leaves on your tree shaped like needles? Scales? Are they broad and flat? How are they arranged on their respective twig? Are they opposite each other on a given twig or do they alternate as they are found along a branch? Are they singly present or are they compound leaves, having more than one leaflet making up each individual leaf? The basics of leaf anatomy continue in the first section of the book with a bit of vocabulary around the parts of a leaf, a bit of jargon, perhaps, but necessary. The back half of the book gives up two full pages per species with plenty of useful information and (gasp) multiple color photos of each tree. My favorite tip offered on page 8: “Relax and have fun. Even professional foresters occasionally have trouble identifying trees.” Too right.**

OK, so you’ve got this book or that book and you’re standing next to this tree or that tree, how do you actually figure out what tree it is? Well, it’s entirely likely that you do not in fact have this book or that book because you were not expecting to run into an unknown tree. Or rather, you were working through today’s list and you did not have “Meet a New Tree” scribbled in your planner, so you ducked out of the house utterly unprepared for this task. Not to worry. There is, as the kids might say, an app for that. Of course there is.

And a good thing, too, Margot adds, because “Meet a New Tree” should, honestly, be a default item on your daily agenda.

Apps for tree ID

There have bubbled up through the dense foam of smartphone living in which we find ourselves floating, a number of applications that offer assistance with plant identification. Many, in fact. And I suspect that’s a good thing. I suspect.

I’ll not opine on the whyfors of dopamine dosing, except to say that our new search for lost time may be a super-short game of hide and seek. It’s right there in your pocket. Or hanging off your belt, or on your dash, or in your hand, purring softly under your eager fingers… The availability of all that information and pseudo-information and disinformation is, frankly, numbing to my pre-cellphone self. I have struggled with this technology over the last quarter century and have come to enjoy a relatively painless coexistence with the magic rectangle in my front pocket.

So many apps. I’ll note one in this little slice of text and that’s iNaturalist. It’s free, it’s relatively easy to use, even for old folks (smile emoji inserted here) and it’s pretty darn handy. I appreciate the fact that the app will take a guess at whatever it is you have snapped a picture of and loaded in, and then allow the greater community of experts (some legit, some with quotation marks) to weigh in on your choice. Crowdsourcing at its finest. Mind you, just because a bunch of folks agree on a thing does not necessarily make the thing true. They could all be wrong, yes, that can happen, but not often. In my experience, this app has been great for identifying plants “in the field”.

One more, then I’ll stop, I promise. There is a wonderful app, Flora of the Southeastern United States, developed by a team of folks centered around the North Carolina Botanical Garden and aforementioned Herbarium: Alan Weakley, Michael Lee, Scott Ward, Chris Ludwig and Katie Gibson. While not free, this app is amazing in its depth of information and area of coverage. It is easy to navigate and use and can be employed in areas without wifi. A real-life, honest-to-goodness two-thousand-page tome all folded up and tucked safely away in your sack. I’m less than excited by cliches like “game changer”, but this one is on the list, at least if it’s plants you’re looking to get to know a little bit better.

Oh my, would you look at the time? Please come back and visit next month. I’m heading out as there is still daylight and it is still warm enough to saunter in light layers. It’s a poor sort of gardener who does not visit gardens. So that’s next on my list of things to do.

To borrow Ken Moore’s obligatory sign-off…Cheers!

Ken Moore in the Garden

A few notes from Margot

* Bluestem is one of 13 conservation cemeteries in the U.S. that support habitat restoration, land conservation and natural burials. We’re a working nature preserve in Cedar Grove, just 10 minutes north of Hillsborough. Come out any day from dawn till dusk to walk the 4-plus miles of trails that traverse our 87 acres of transitional woodland and Southeastern grasslands, do some excellent birding or sit in quiet reflection. Look for me leading folks on nature walks, talking about vultures or helping with a homegoing.

** One of my favorite quips from the Bluestem walk was when we were gathered around what most of us felt was a shortleaf pine and a rigorous, good-natured discussion was occurring about what various keys had to say about the species. Noted Mr. Neal, “Trees don’t always follow the rules”. I’m thinking that would look pretty great on a t-shirt.

All photos by Geoffrey Neal except as otherwise noted.

Geoffrey Neal is the director of the Cullowhee Native Plant Conference. See more of his photography at soapyair.com, @soapyair and @gffry. Margot Lester is a certified interpretive naturalist and professional writer and editor. Read more of her work at The Word Factory.

About the name: A refugium (ri-fyü-jē-em) is a safe space, a place to shelter, and – more formally – an area in which a population of organisms can survive through a period of unfavorable conditions or crisis. We intend this column to inspire you to seek inspiration and refuge in nature, particularly at the Arboretum!