By Margot Lester

I’m usually here on Chapelboro talking about native plants or safety tips, but this column’s all about changing the way we look at vultures — especially since this Saturday, September 6 is International Vulture Awareness Day!

A lot of folks are turned off by these prehistoric avians and depictions of them in popular culture don’t do much to change those feelings. Neither does the negative connotation around the term “vulture” itself. But it hasn’t always been that way. The origin of their scientific family name, Cathartidae, is from the Greek word for “purifier”—a much more positive association.

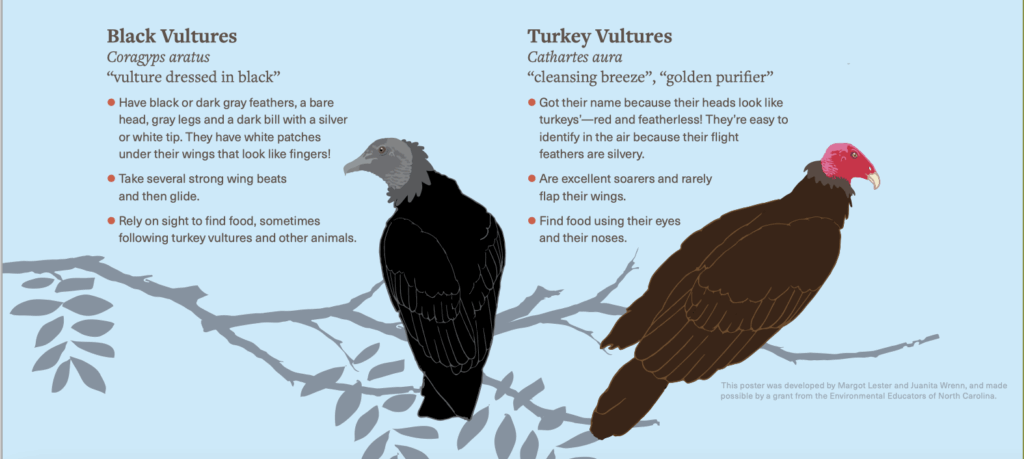

Here in Orange County, we have two species, the black vulture (Coragyps aratus) and the red-headed turkey vulture (Cathartes aura). I know in some places, they’ve got a reputation as nuisance birds, but that’s mostly because of decisions we humans make around garbage disposal. Mostly, vultures are helpers. I’ll get to that in a minute…

Vultures are often found around dumpsters and other trash receptacles, like this committee of black vultures (Coragyps aratus) in downtown Hillsborough, where some find them a bit of a nuisance. Photo by Margot Lester

My life with vultures

Vultures have been a part of my life all my life. Growing up out in the country past University Lake, we’d frequently see a wake of vultures along the side of the road, in a pasture and sometimes even in the woods, quietly picking away at something. (Vultures don’t sing like other birds, but they will hiss when annoyed.) It’s not unusual to see both species hanging out together.

We’d also see them soaring high above, even further up than the hawks. They’re easy to differentiate from this vantage point, too. Turkey vultures have silvery white features on the undersides of their wings and do more gliding than wing-flapping. By contrast, black vultures have white “fingers”, as my Granny called them, under the tips of their wings and flap their wings more than their relations. A flying flock of vultures is called a kettle, supposedly because as they rise and circle, they look like bubbles in boiling water. Quaint!

When I lived in Hollywood for a spell, I was in the land of their “cousin”, the California condor (Gymnogyps californianus), though I never was lucky enough to see one in the wild (they continue to be critically endangered).

Back in 2016, when I started doing voter protection work, a committee of vultures would arrive just after me at the Efland Ruritan Club polling place and stay through my shift. Some folks might think that was a bad omen, but nothing bad has ever happened to me in the company of these creatures, so I, like many before me, considered them witnesses and bodyguards for me and the voters.

Use this information to help you identify vultures. Illustrations by Juanita Wrenn.

Why vultures are cool

See! I promised I’d get back to why you should change your mind about vultures.

What these birds may lack in cuddliness, they more than make up for in community service.

They clean up road kill and other carrion with remarkable efficiency. They locate dead animals quickly, using sight and—for turkey vultures—smell. (Supposedly, those redheads can detect the tiniest concentrations of ethyl mercaptan, a gas emitted during decomposition, from as far as two miles away!).

Once located, they begin their orderly and efficient business. Vultures’ quick work helps reduce greenhouse gas emissions since carcasses also produce methane and CO2 as they decompose—and the longer they’re left alone, the more gas goes into the atmosphere. The birds also consume bacteria and germs in the carrion that are harmful to people. Microbes and acids in their systems neutralize pathogens like anthrax, botulism, cholera and rabies—keeping them out of the ecosystem as they cycle nutrients into it.

When vultures gather to feed, it’s called a wake. These black vultures are processing a skunk carcass in a creekbed. Photo by Margot Lester.

I know, cool. And there’s more.

Vultures are helpers, too

They’ve been helping people like this all the way back to our earliest incarnations. Anthropologists believe early humans followed vultures to find freshly dead meat for food. And in many cultures, the birds are seen as guardians and protectors, perhaps because of their quiet roosting.

Beyond guiding folks to food, vultures have been, through the ages, considered psychopomps, a very cool word for entities that are go-betweens connecting the living and dead, and/or “soul-carriers” that escort people to the afterlife. A few other black birds are also associated with these activities, including ravens and crows. It helps, too, I guess, that they are shrouded in the color of mourning. I never thought too much about this until I started volunteering on the Bluestem burial crew.

We mostly see them wafting high above the restored grasslands and forest. Sometimes we’re lucky enough to catch them roosting, some in majestic, horaltic poses depicted across millennia, on the old outbuildings. I take a lot of comfort in their presence, especially when we have assembled for a burial (and they have yet to miss one that I’ve been at). Burial crew members are there to see to the family and witness the transition of their loved one from this space to the next—and the vultures are doing the same.

Find more vulture facts

I hope I’ve helped you change your mind about vultures and perhaps inspired you to learn more. If you’re curious, you can find more facts on Bluestem’s Everyday Conservation page and come for a visit to see our friends. Or just remember to give the next committee, kettle or wake you see a nod, a wave and a thank-you.

Was this article helpful? Take this 3-question survey to tell us how we did.

Margot Lester is a certified environmental educator and interpretive naturalist in Carrboro. She received a grant from the Environmental Educators of North Carolina to develop interpretative materials on vultures for Bluestem Conservation Cemetery’s Everyday Conservation program. Juanita Wrenn created the illustrations and designed a banner and fact sheets.