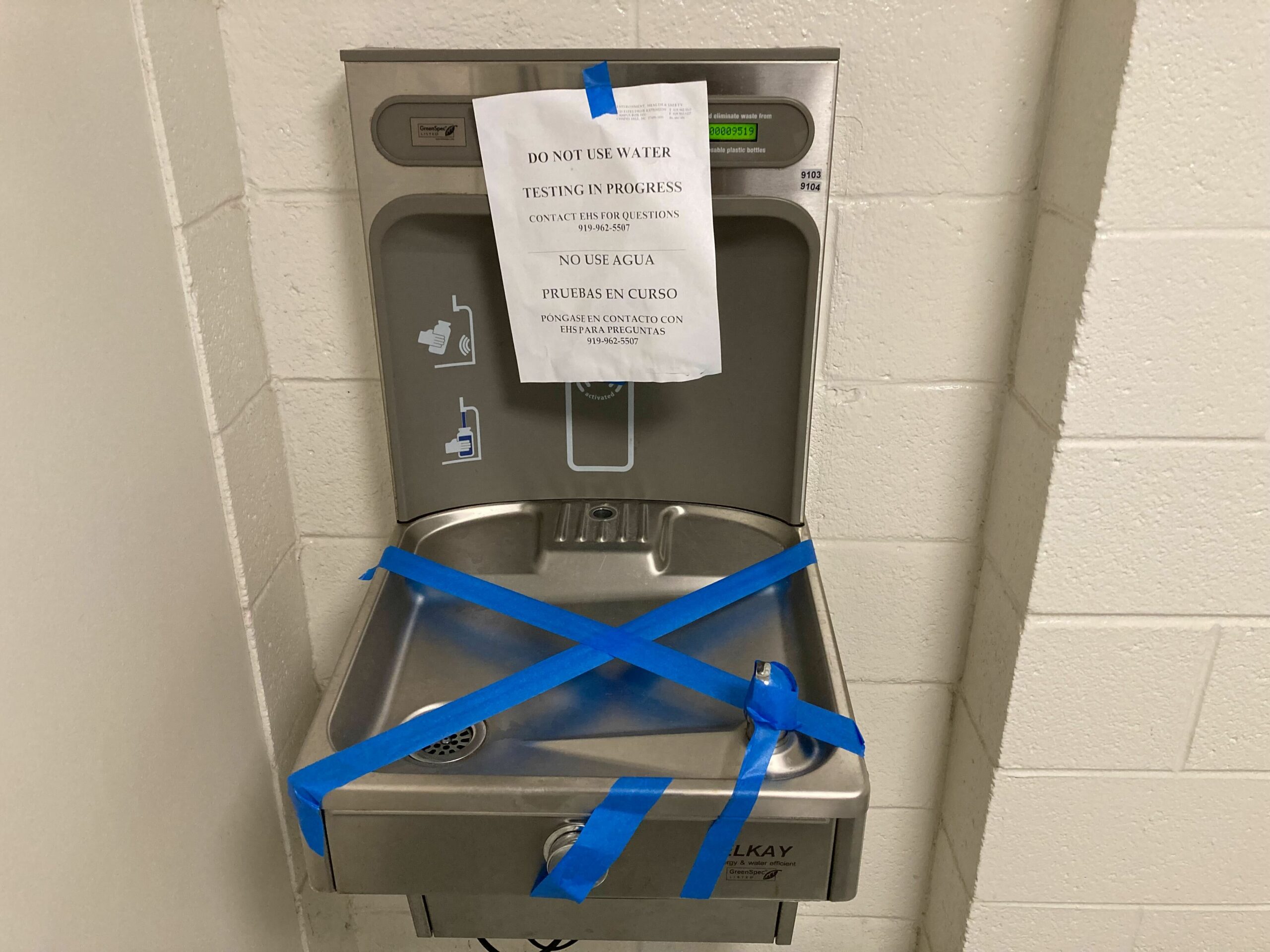

After testing every single drinking water fixture in university facilities and taking hundreds of them offline, UNC says it is officially finished with its immediate lead detection efforts and moving on to its next steps.

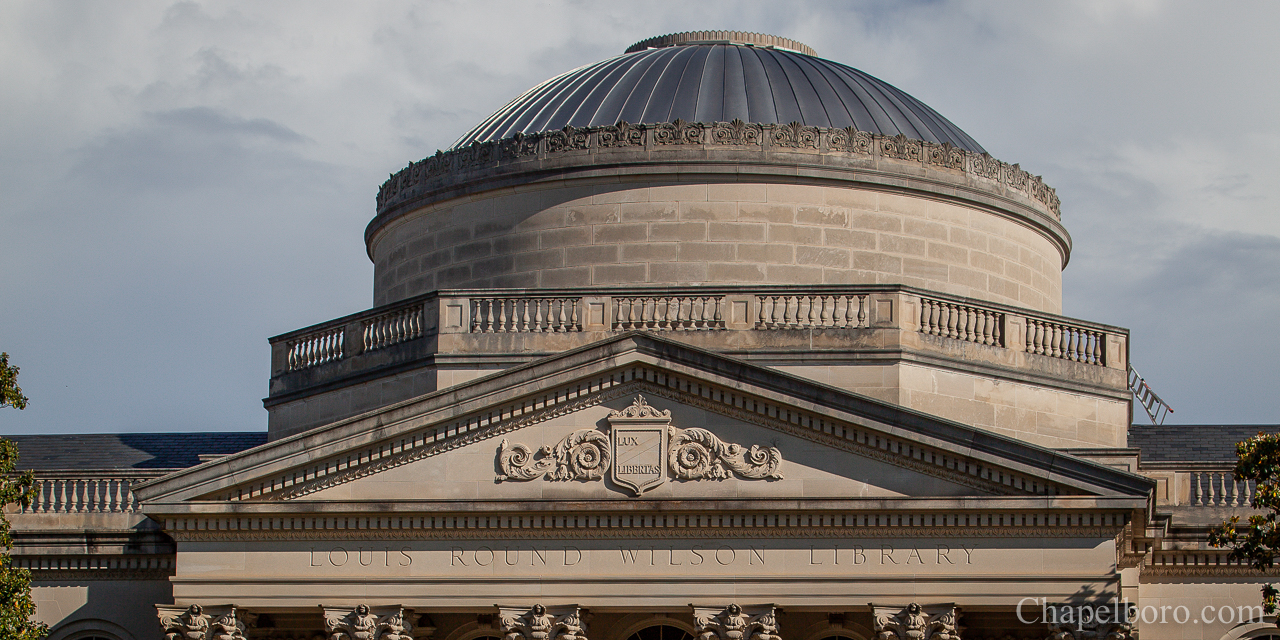

What started as a summer science project testing UNC’s drinking water in 2022 led to a months-long effort on campus to find the presence of the toxic metal. The first official notice of lead in a campus fixture happened September 1, after tests taken from historic drinking fountains in Wilson Library came back with noticeably high levels of lead. The metal is not safe at any level of exposure, but the Environmental Protection Agency does not have any regular testing requirements for universities and it typically takes a significant amount of lead to be ingested for health problems.

Rebecca Fry – an environmental sciences professor at UNC with an expertise in toxicology – says when she heard about the lead last year, she wasn’t stunned.

“Of course I was concerned, but not surprised,” says Fry, “because metals are everywhere in the environment. While we have found it here, I’m quite certain that if other universities looked for lead in drinking water, they would also find it.”

Fry served as an advisor to the university in its subsequent testing efforts, which included taking water samples from every drinking fountain, bottle filler, and sink on campus. The results saw more than 100 university buildings with at least one fixture testing with traces of lead, which were then taken offline and are slated to be replaced.

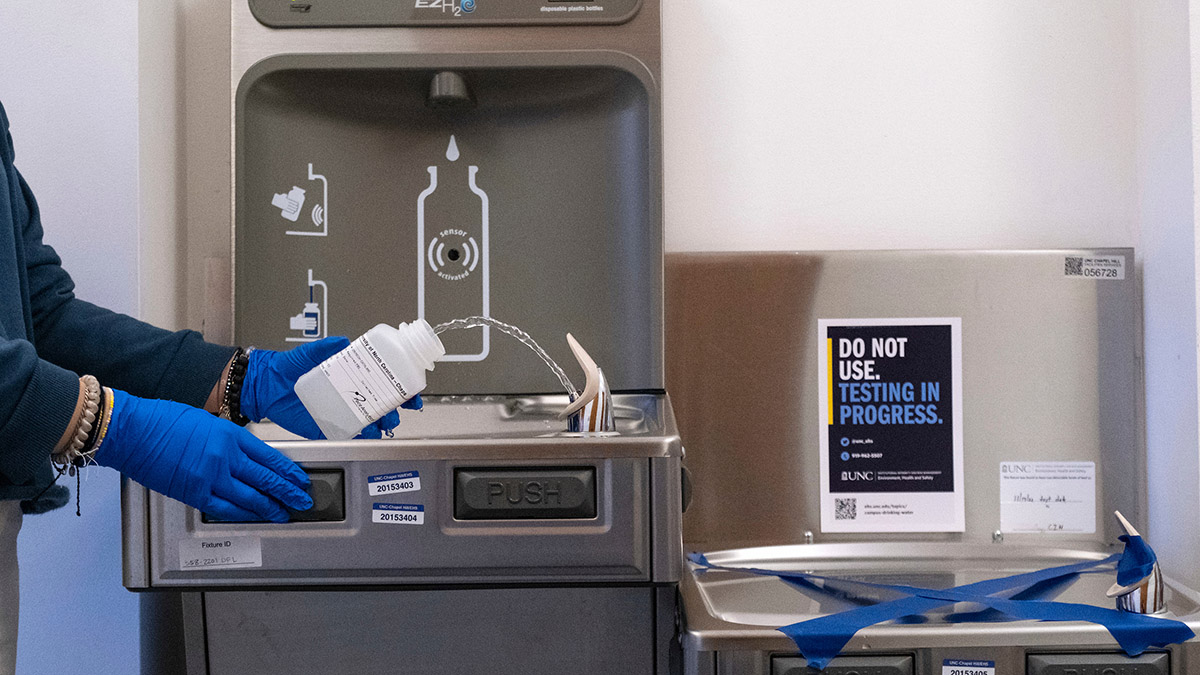

Fry says part of the volume of these results can be attributed to UNC having an “aggressive” strategy to identify problematic fixtures. She describes the effort as a two-day process for each spot tested, as water is flushed the night before two consecutive measurements are gathered.

“Before a sample is collected, water has to be released from the system,” says Fry. “And then early the next morning, samples are collected [from each fixture]. When the testing started, that was through the enormous efforts of [the university department of] Environmental, Health and Safety. And we brought in some students to help and then we brought in some contractors, because this was a lot of work.”

To gather those samples and send them off to a state lab for testing, a group of student volunteers aided the university team for a handful of hours each week. Some of those students came from Fry’s lab, who says it provided an excellent opportunity for hands-on work in the field.

“I’ve had students who participated in that testing,” Fry describes, “tell me it was the most impactful thing that has happened in their four years of being here and really transformed their lives. Several of the students were so impacted that they’re talking about going into careers in environmental science.”

To help accommodate and assuage campus community members concerned about lead exposure, UNC offered free blood lead levels tests during the last seven months. Fry says that everyone who took a test had their blood come back with lead levels in the reference range, or with “normal” amounts. That’s an encouraging sign as the university waits for more analysis of the water samples’ data to determine any broader patterns of lead presence on campus.

Fry adds that one of the most obvious patterns already seen is lead was far more prevalent in UNC’s older buildings than its newer ones – which made for much higher traces during the first months of testing.

“We did this testing in a phased approach, where the earlier phases were focused on our oldest building on campus,” she says. “Certainly, some of those early data points came back higher than the later data points, which were collected from our newer buildings on campus.”

Wilson Library, at the heart of UNC’s campus, opened in 1929. The building was the first to be lead tested by the university during the fall semester and it returned multiple tests with traces of the toxic metal — but dozens of newer buildings also saw fixtures with noticeable levels of lead.

As seen by the dozens of buildings and hundreds of fixtures with high lead levels, however, UNC’s response to the toxic metal will be more layered than just replacing old parts. The university said it will begin testing its older buildings every three years for lead, which Fry says she believes is “a good plan.” Additionally, the Environment, Health and Safety department will test drinking fixtures that previously had lead levels one year at the latest after their replacement.

Fry says she’s “really proud of the school” for its approach in testing and communicating the data to the campus community. She says she hopes the experience is a reminder to everyone at UNC – and elsewhere – about the presence of metals in unexpected places.

“It does highlight,” says Fry, “the importance of the environment in our lives every day – in the water that we drink, in the air that we breathe, the environment is all around us. So, a learning point really is that the environment is there and there’s lots that we need to do to understand what’s present in [it].”

George Battle, the Vice Chancellor for Institutional Integrity and Risk Management and the lone UNC official provided for interviews on its lead testing response, was unavailable for comment before publication. In a message to the community on March 30, however, Battle thanked the university community for its patience and cooperation. He added that blood lead level testing will stop being free to everyone at the end of April and any further questions on the university’s process can be sent to Environment, Health and Safety services.

A full list of the affected fixtures in the specific UNC buildings, visit Chapelboro’s tracker article based on the university’s reports. The information can also be found on the Environment, Health and Safety department’s website — although UNC said the data will be archived at the end of the spring 2023 semester, which is protocol for other EHS testing results.

Featured photo via Jon Gardiner/UNC-Chapel Hill.

Chapelboro.com does not charge subscription fees, and you can directly support our efforts in local journalism here. Want more of what you see on Chapelboro? Let us bring free local news and community information to you by signing up for our biweekly newsletter.