To reflect on the year, Chapelboro.com is revisiting some of the top stories that impacted and defined our community’s experience in 2022. These stories and topics affected Chapel Hill, Carrboro and the rest of our region.

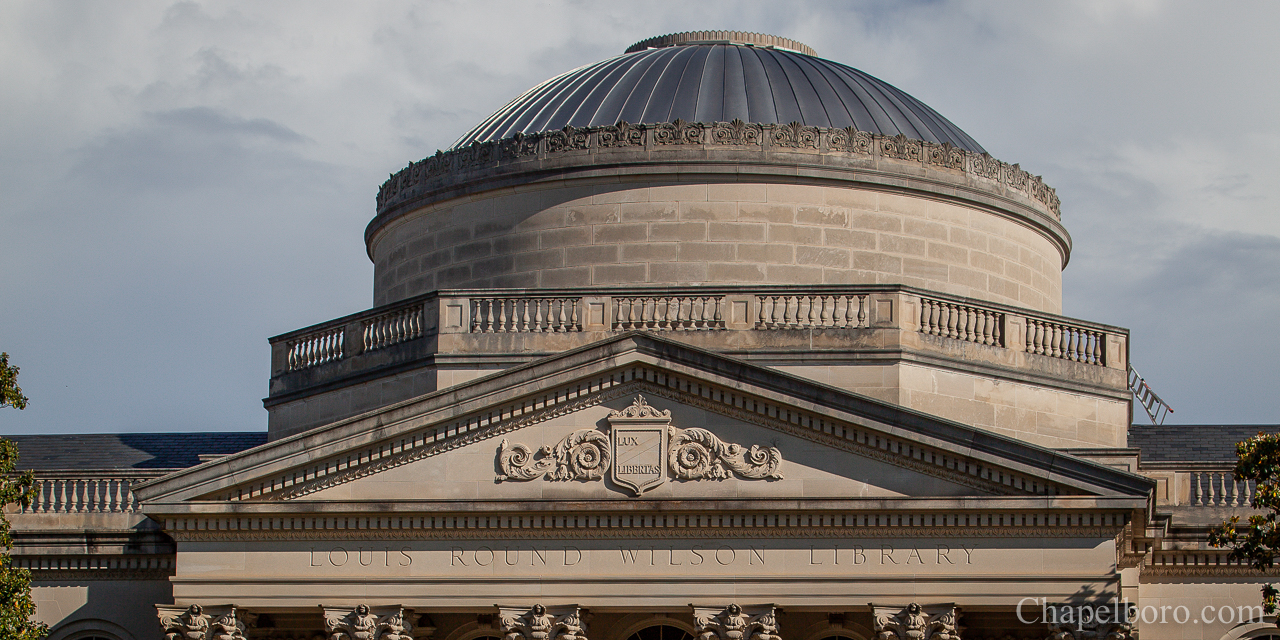

What started as a learning exercise for some early college students rapidly turned into a campus-wide issue, after traces of lead were found in several water fixtures in Wilson Library in August. The university began testing other buildings and quickly found the chemical was not isolated to one fixture — although not a problem with the university’s water source itself. Since then, hundreds of additional fixtures have been shut down to study the problem.

Drew Coleman, who is the Chair of UNC’s Environment, Ecology and Energy Program, regularly works with early college students over summers to help teach how science is attainable for students of all backgrounds. One project he chose this year for two Roberson County students was sampling and testing water from difference campus buildings for traces of lead. Coleman said he believed the exercise would demonstrate how to see if water is truly clean.

But when testing samples from South Building and Wilson Library, the results led the UNC professor to a major realization.

“We had deliberately prepared huge samples,” Coleman told 97.9 The Hill in a November interview, “because we anticipated low, low levels of concentrations of lead. And the samples were running like there was a lot of lead in the machine, so we knew we had problems.”

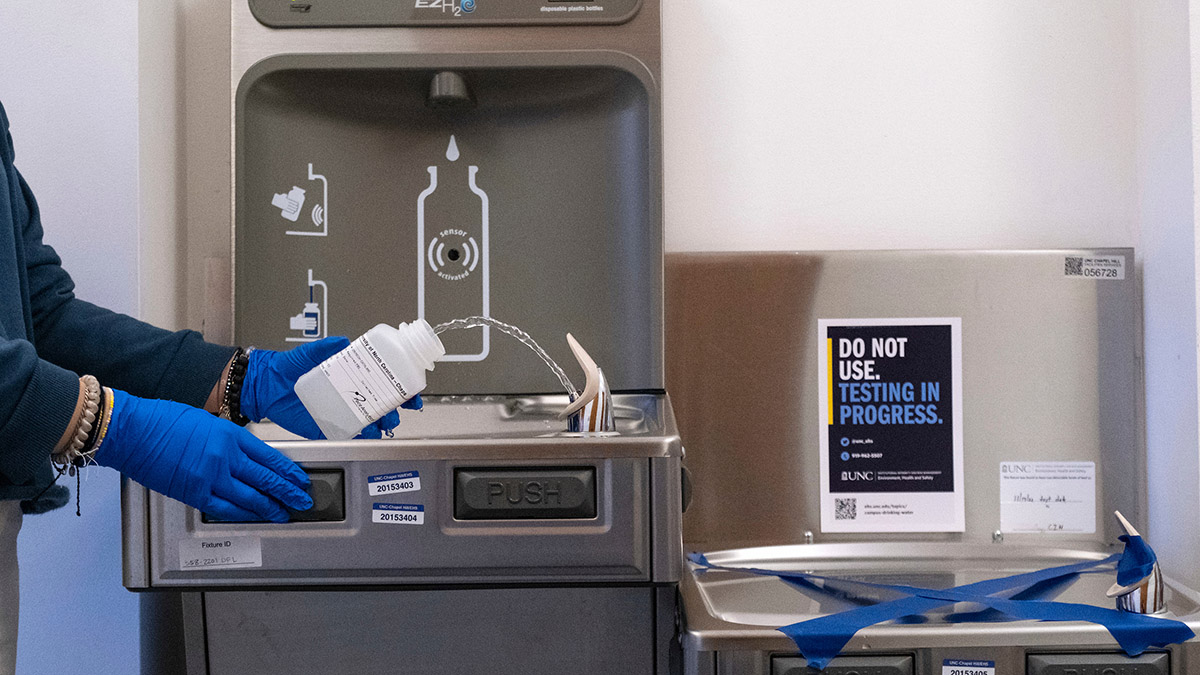

The university’s Environment, Health and Safety division conducted follow-up testing to confirm Coleman’s results with traces of lead. On September 1, UNC sent out a campus-wide message confirming the discovery in three older drinking fountains at Wilson Library. From there, a widespread testing plan was created to check thousands of water fixture across UNC for potential traces of the chemical.

Wilson Library, at the heart of UNC’s campus, opened in 1929. The building was the first to be lead tested by the university during the fall semester and it returned multiple tests with traces of the toxic metal.

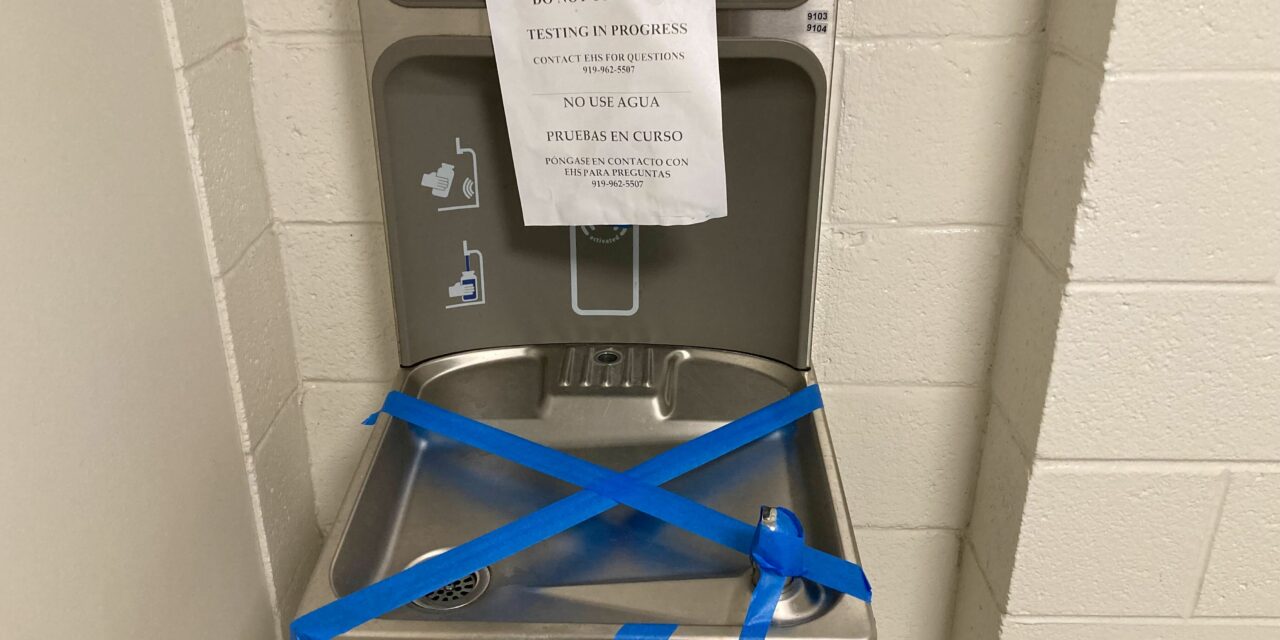

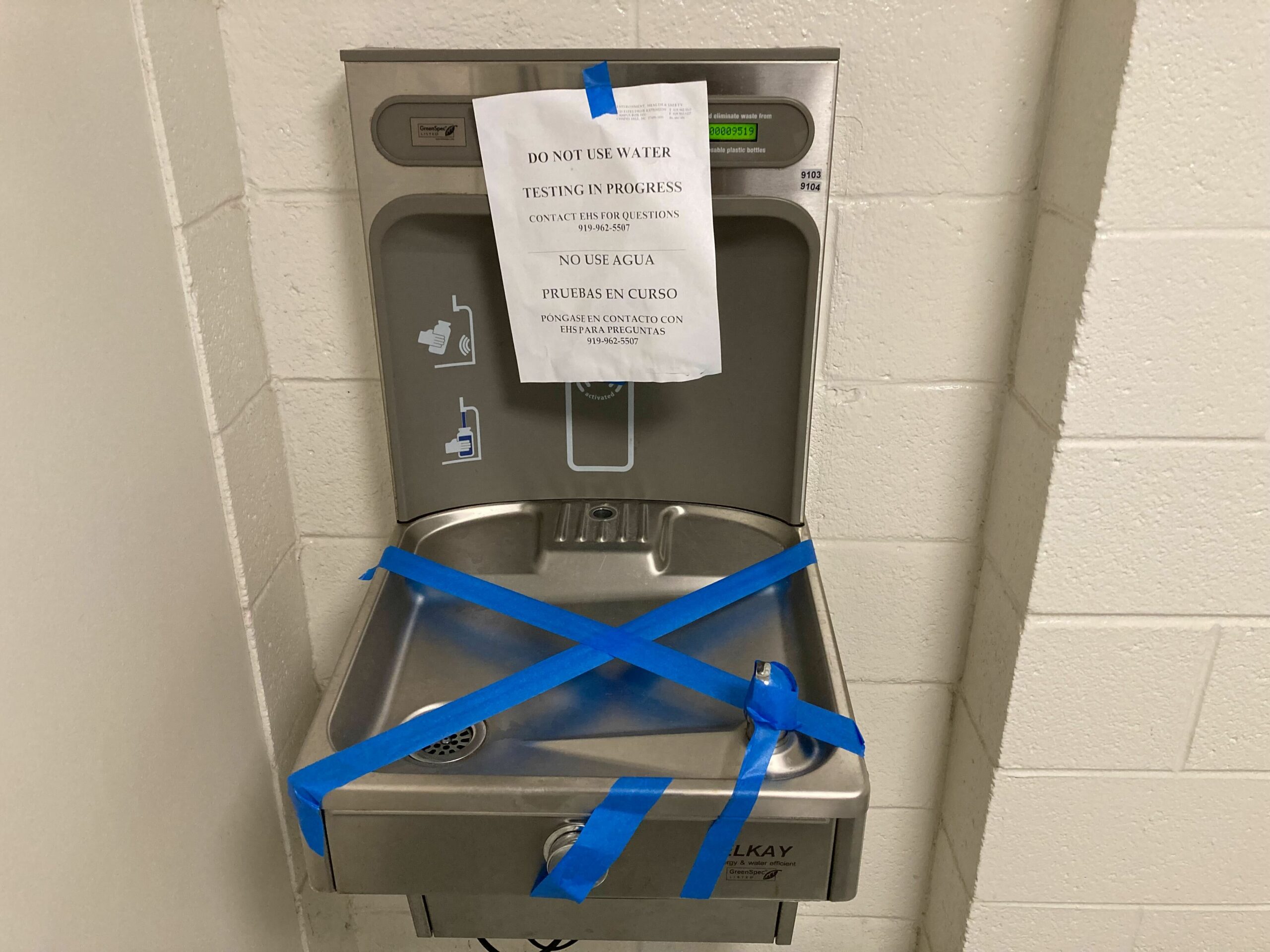

The Environmental Protection Agency does not require college and university to conduct regular lead testing for drinking water sources, with UNC saying it only previously tested buildings upon request by occupants. Once a fixture with traces of lead is discovered, however, the EPA requires those systems or providers to take action to “reduce any lead concentration at or above 15 parts per billion.” While the vast majority of UNC’s positive lead tests returned numbers under that threshold, the university has taken each affected water fixture out of service for further testing and examination.

UNC’s tested water fixtures across three phases so far. Phase One exclusively checked water fixtures that potentially had lead components due to their age and construction. Phase Two, which finished in late October, tested all water fixtures in buildings built during or before 1930. Phase Three, which the university says is ongoing, tests fixtures in buildings built in or prior to 1990. UNC is also doing “preview sampling” of campus facilities built after 1990 to determine whether a Phase Four of the remaining buildings and fixtures is necessary.

The list of buildings with affected water fixtures is perhaps longer than the list of buildings whose fixtures tested as clean. Overall, the testing process has yielded hundreds of results with traces of lead, with more than 100 campus facilities seeing at least one water fixture taken offline during the testing. UNC has alerted the occupants of affected buildings through emails, as well as posts on the Environment, Health and Safety department’s website. Buildings ranging from residence halls and academic buildings to sports stadiums and public safety facilities have returned test results with lead — with number of fixtures peaking at 57 in-room sinks for Spencer Residence Hall, which was constructed in 1924.

While it takes a significant amount of lead to be ingested to cause health problems, the Environmental Protection Agency states there is no safe exposure to the toxic metal in water. As a result, UNC now offers free blood testing for any campus community member who requests one and potentially ingested lead.

As of December, the UNC Environment, Health and Safety department says fixtures returning lead results will be replaced or repaired — but no further information on process, timeline or future prevention has been shared. Most buildings across campus have temporary, alternative water dispensers installed for drinking.

Chapelboro.com does not charge subscription fees, and you can directly support our efforts in local journalism here. Want more of what you see on Chapelboro? Let us bring free local news and community information to you by signing up for our biweekly newsletter.