A partisan gerrymandering trial began Monday in North Carolina, where election advocacy groups and Democrats hope state courts will favor them in a political mapmaking dispute that the U.S. Supreme Court just declared is not the business of the federal courts.

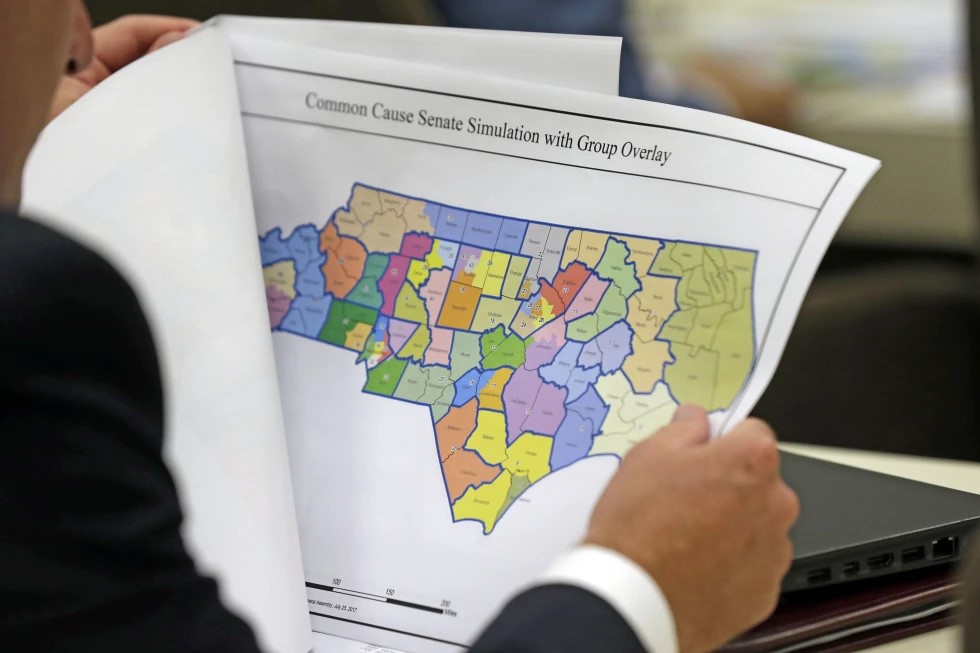

Lawyers for Common Cause, the state Democratic Party and more than 30 registered voters who sued contend Republican lawmakers so etched politics into the state House and Senate district lines that the constitutional rights of Democratic voters were violated. Republicans counter that the Democrats are simply asking courts to use “raw political power” to take redistricting responsibilities from the legislature. Both sides pitched their arguments at the start of the trial, expected to last up to two weeks.

It commenced less than three weeks after the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in a separate case involving North Carolina’s congressional map that it’s not the job of federal courts to decide if boundaries are politically unfair. But Chief Justice John Roberts also wrote in the majority opinion that state courts could have a role to play in applying standards set in state laws and in their constitutions.

The plaintiffs in the North Carolina case are seeking just that, saying 95 out of the 170 House and Senate districts drawn in 2017 violate the state constitution’s free speech and association protections for them. They also say the boundaries violate a constitutional provision stating “all elections shall be free,” because the maps are rigged to predetermine electoral outcomes and guarantee Republican control of the legislature.

A partisan gerrymandering lawsuit in Pennsylvania citing a similar provision in that state’s constitution was successful.

“State courts do not need to sit idly by while people’s constitutional rights are being violated just because the U.S. Supreme Court refused to act,” plaintiffs’ attorney Stanton Jones told a three-judge panel in Raleigh hearing the case. His clients want new maps drawn for the 2020 elections.

Despite a large party fundraising advantage during the 2018 cycle and candidates in nearly every legislative race, Democrats could not obtain a majority in either the House or Senate — a failure Jones attributes to the skewed boundaries.

But the Republicans’ chief attorney, Phil Strach, said in his opening statement that the Democratic Party’s own data will show the party could win majorities under the challenged plans. Democrats currently hold every House seat in Wake and Mecklenburg counties — the state’s two largest counties by population — but they are still challenging every district in those counties.

Democrats did pick up state legislative seats in 2018 under House and Senate maps that had been slightly adjusted compared to the 2017 plans. Republicans lost their veto-proof control last year but still hold majorities. Democratic Gov. Roy Cooper now has more leverage at the General Assembly, but by law he cannot veto redistricting plans.

Strach says state courts and the constitution already have put limits on redistricting that discourage egregious partisanship, while allowing for some consideration of partisan advantage and protecting incumbents.

“There is no way to know what a fair map looks like,” Strach said. “That would require the court to decide essentially how many Republicans and Democrats should be in the legislature.”

Jones said his clients plan to use files from Tom Hofeller, a now-deceased GOP redistricting consultant who helped draw the 2017 maps, to “prove beyond a doubt that partisan gain was his singular objective.”

Hofeller’s estranged daughter alerted Common Cause to the existence of his computer files, which were later subpoenaed. Stephanie Hofeller is expected to testify during the trial. Witnesses on Monday included Common Cause’s state director and Democratic legislators.

The Republicans’ lawyers tried unsuccessfully to keep the 35 files out of the trial, saying they didn’t prove the GOP legislators who ultimately approved the maps were led by excessive partisanship. Strach said the plaintiffs were trying to turn Hofeller into a redistricting “bogeyman.”

Some of Hofeller’s files ended up being used in separate litigation in other states challenging a plan by President Donald Trump’s administration to include a citizenship question on the 2020 U.S. census.

The case marks at least the eighth lawsuit challenging North Carolina maps since the current round of redistricting began in 2011. The lawsuits resulted in redrawing congressional lines in 2016 and legislative districts in 2017 — both to address racial bias.