North Carolina was the first state in the country to require traffic stop records. Any time a car was pulled over, the officer filled out a report. Now with 13 years worth of data, the trends hold answers to questions about racial profiling in policing.

UNC political scientist Frank Baumgartner has been studying the data for years, and said there’s an undeniable link between people of color and car searches.

“The striking numbers are that if you’re a young Hispanic or a young African American male, in the situation that you get pulled over, you’re much more likely to be searched than anyone else in the population,” Baumgartner said.

Age and gender were also reflected in the data.

“A young white male is also more likely to be searched than a female or an older person,” Baumgartner.

Frank Baumgartner discussed his findings with Aaron Keck on WCHL.

Baumgartner is trying to answer the question why cars pulled over for minor offenses, like expired tabs or broken headlights, are more likely to be searched.

“It might be that the officer wants to search that car because they have a visual cue that they may be involved in drugs or something. So the officer first decides that he wants to search the car and then finds a way to pull that car over.”

But this type of policing walks the line of racial profiling – especially in certain areas of town. ‘Policing by place’ is a tactic that patrols high crime areas more aggressively – something that Baumgartner says also highlights racial inequities.

“If you live in a neighborhood that is not one of those crime hot-spots, that’s a relatively nice neighborhood, the policing is a lot more soft touch. And those neighborhood distinctions tend to be correlated with race. So there really is a different style of policing depending on who you are and where you live.”

If a white driver is pulled over, there is a two percent chance that their car will be searched, Baumgartner said, but a four percent chance for a person of color. From 2002 to 2015, over 20 million recorded police observations show that these racial profiling trends are not improving.

“Rather than being steady or decreasing, they’ve actually been steadily increasing so that by 2013 they were 150 percent more likely,” Baumgartner said. “So it’s moving in the wrong direction.”

This trend also follows the ‘contraband hit rate’ which refers to the likelihood that a search leads to finding drugs, weapons or some other form of contraband. Even though racially profiled searches have increased, Baumgartner said the contraband hit rate has not.

“The contraband hit rate has not changed, so there’s an increased targeting over time of minority drivers.”

To try and prevent racially profiled searches without probable cause, Chapel Hill, Carrboro, Durham and other cities have instituted a written consent form. Previously, when officers asked for permission to search cars, community members said they felt intimidated by the question. Baumgartner said a written consent form seeks to give people the choice to opt out of searches.

“If the officer does not have probable cause, he has to conduct what’s called a consent search, and that might be an area where there is a likelihood of bias. So one solution is to not only have the officer ask for your permission, but to have you sign a waiver that explicitly recognizes that you have the right to say no. And when that happened, the number of consent searches decline precipitously.”

Baumgartner said he worries these trends will alienate certain demographics of the community and weaken their trust in law enforcement

“I think we are alienating a lot of young men. And a lot of older men and members of minority communities are accustomed to the idea that they may have been pulled over for reasons that they cant really get their head around.”

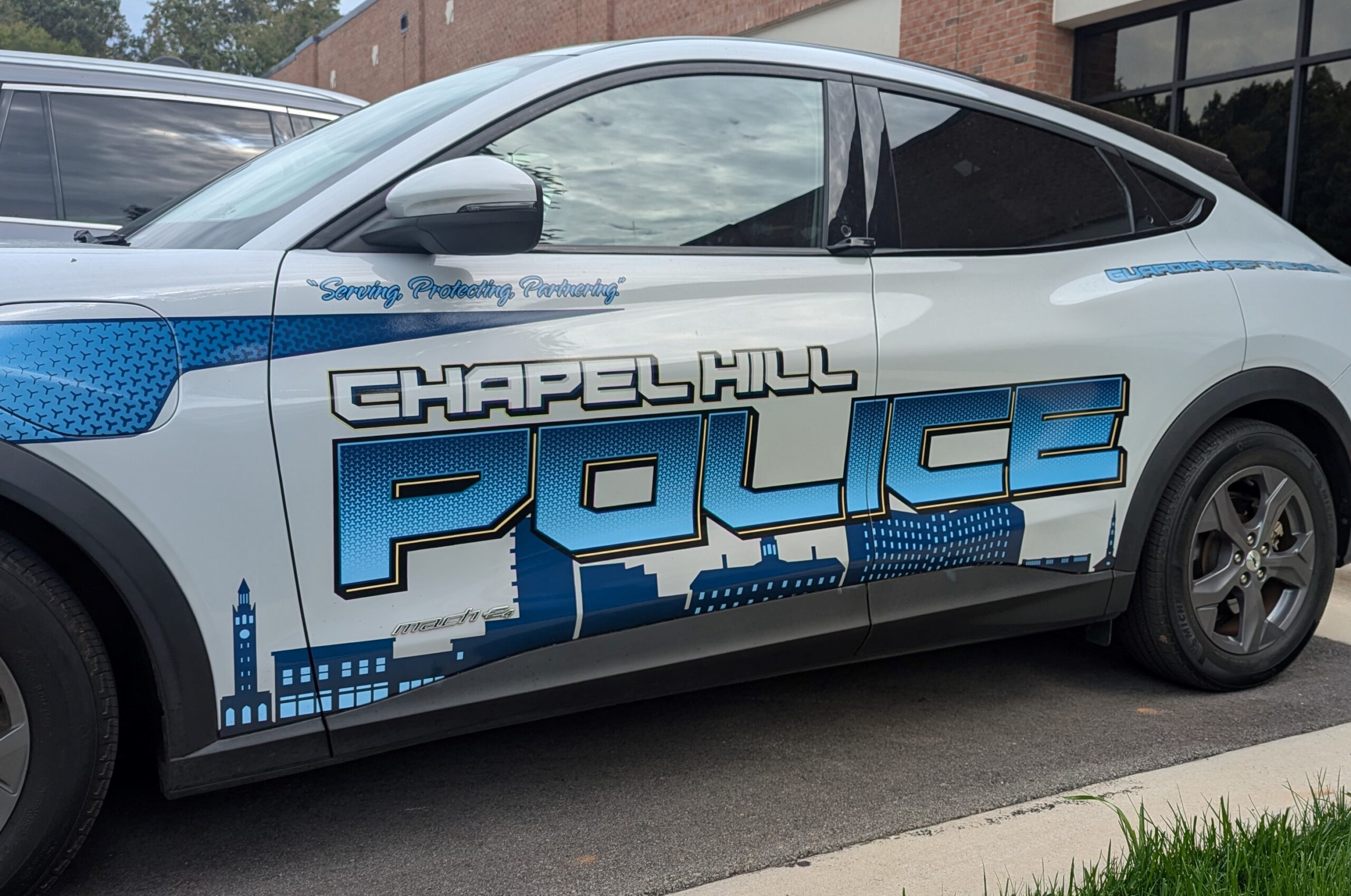

Chapel Hill Police Chief Chris Blue said that he’s using the data to improve his force’s policing methods. He says he supports the open data policy and hopes it will help the community understand their work.

“I think the overall message is that we’re doing our community’s work, so the more information that we can put out about what we are doing on your behalf, it is your information we are your employees, we want to continue to create more and more opportunities for that information to be out there,” Blue said.

Chief Blue also said he hopes to offer clarification about any concerning trends and hopes that by monitoring his team’s work, they can find ways to improve.

“It’s that old idea that you can expect what you inspect, coupled with some real reflection about what’s the thinking behind your decision.”