Gun violence kills more than 40,000 Americans each year, making it a particularly urgent issue. But it’s also a highly charged and polarizing issue, making it hard for policymakers to achieve any progress. On the federal level, lawmakers recently announced a major bipartisan agreement – but even there, its scope is limited and its passage remains uncertain.

Are there other ways of approaching the gun violence issue, that can help us more easily make lasting, meaningful progress?

In Chapel Hill, and on university campuses nationwide, epidemiologists and other scholars are beginning to tackle gun violence from the perspective of public health.

“If you look at something that causes over 40,000 deaths a year, that’s a public health issue,” says Beth Moracco, the associate director of UNC’s Injury Prevention Research Center (IPRC). “What I’ve found is that if you take it from the perspective of ‘this is something that’s causing a lot of death, how can we make it safer?’, that’s where I think we do find some common ground that can take the politics out of it and really look at the science.”

Moracco says the science tells us a great deal about the underlying causes of gun violence.

“The typical public-health causal factors can be underlying: mental health, intimate partner violence, sexual violence,” she says. “Addressing those causes can reduce lethal and non-lethal violence.”

And while the debate about guns tends to revolve around mass shooting incidents, Moracco says from a public health perspective, the greatest impacts actually result from smaller incidents, like intimate partner violence and domestic violence.

“[And] actually, it’s death by suicide that is the leading type of death perpetuated by gun violence,” she says.

Given that, Moracco says a public-health approach tells us we can make a lot of headway by addressing mental health issues, and also by taking steps to prevent domestic violence.

But Moracco says public health also tells us the guns themselves are important too.

“The fact that there is easy access to a very lethal means…just kind of amplifies the effect,” she says.

In that vein, some public health researchers are advocating for ‘red flag’ laws, restricting firearm access to people who have been specifically deemed a danger to themselves or others.

“Having domestic violence protective orders for gender-based violence prevents violence in their homes,” says Shabbar Ranapurwala, the assistant director for research methods at the IPRC. “[Or] having extreme risk protective orders for people who are in a depressed state and are likely to hurt themselves or even others around them, so that they don’t get access to firearms in those acute moments. Those kind of things can prevent larger calamities from happening.”

Moracco adds that – at least in North Carolina – that doesn’t necessarily mean having to add more laws to the books.

“Particularly in North Carolina, we already have [strong] legislation, but there may be issues with implementation and enforcement,” she says. “North Carolina is actually the only state that requires judges to inquire about access to guns during the [domestic violence] protective order hearing process. And there’s an opportunity there to restrict access, [but] we’ve seen in our research that there are issues around implementation.

“So we know those laws can be effective, other research has shown that in other states, but what we are seeing are some gaps in implementation. So that’s one place that we could start.”

And Ranapurwala adds that implementation of other laws is exactly where expanded background checks can become relevant.

“If somebody has a domestic violence protective order against them, and they go to buy a firearm,” he says, “unless you do a background check on them, you are not going to be able to implement that.”

While the debate about gun laws focuses mainly on the state and federal level, concern about gun violence as a public health issue has trickled down to the local level as well. There, health officials are also beginning to take their own steps – even health officials who have been spending much of their time focused on COVID-19.

“It is a public health issue,” says Orange County Health Director Quintana Stewart. “We try to do our part [at the Health Department] and educate about safety: for those that have guns, make sure you lock those up, and have the appropriate training, and keep it out of reach of your children. We try to do our part with that – but it is something I think that we would have to tackle, the whole community, working together.”

The bipartisan agreement recently announced on the federal level does include funds for states who enact red flag laws and additional federal funding for mental health. It includes limited, though not extensive measures to expand background checks. But it does take additional steps to prevent domestic abusers from obtaining firearms.

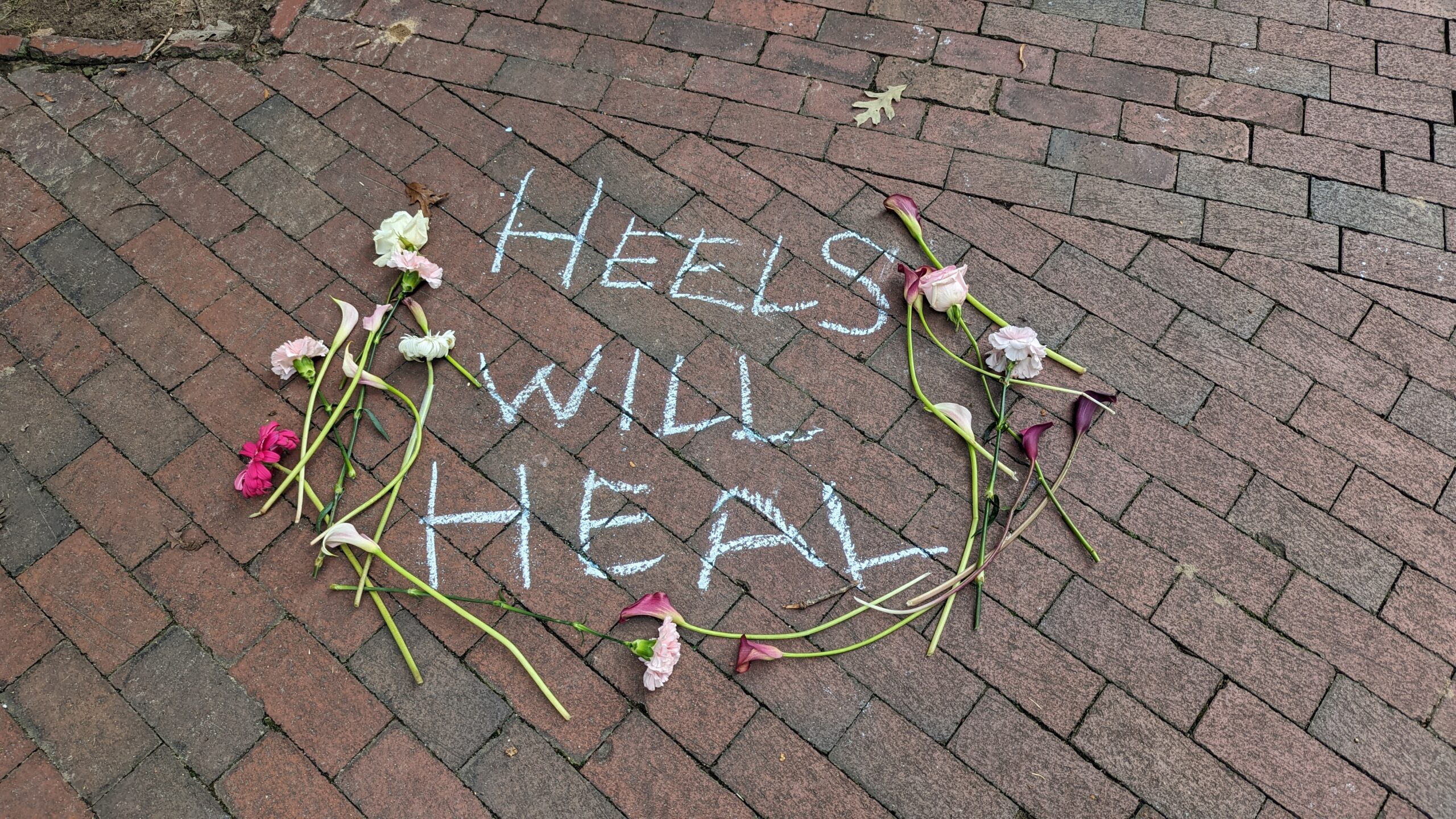

Photo via Associated Press.

Chapelboro.com does not charge subscription fees, and you can directly support our efforts in local journalism here. Want more of what you see on Chapelboro? Let us bring free local news and community information to you by signing up for our biweekly newsletter.