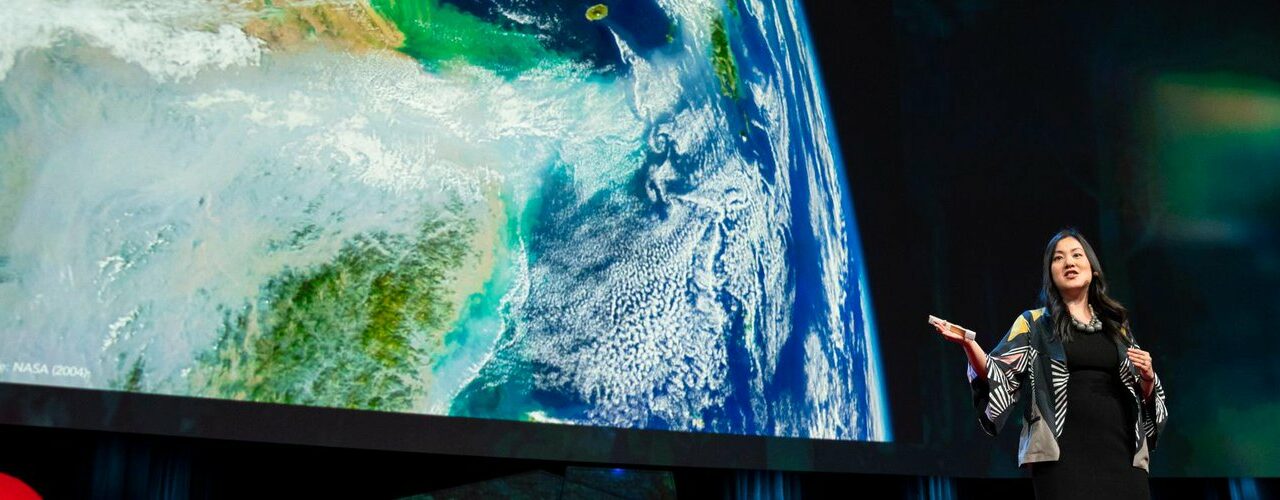

Angel Hsu is an associate professor in UNC’s environmental ecology program. She recently spoke with 97.9 The Hill about her work as the director of a data-driven envirolab and how technology can teach us more about combating climate change on a local government level.

Check out highlights of the conversation below, which are lightly edited for clarity, and click here to listen to the full conversation!

Andrew Stuckey: I wonder if you could just give us kind of an overview of what your research focus is. It’s pretty fascinating.

Angel Hsu: Broadly speaking, I study the intersection between urbanization and climate change. I’m really interested also in how data science and digital technology can help us to get better information about how different environment and climate change policies are performing, particularly at the city and the local scale.

Andrew Stuckey: So that said, how do you feel about Chapel Hill’s performance on that at this time?

Angel Hsu: Well, I think there’s a lot of things that Chapel Hill is doing right. They have a climate change plan that’s been in place for the last couple of years. They are measuring where their greenhouse gas emissions are coming from. It is coming from transport buildings from waste, for example. And they have specific targets in place to reduce their emissions. One of the targets that they have in place is to reduce emissions 26 percent to 28 percent by 2025.

Andrew Stuckey: Let’s talk about the data-driven environ lab. How did that start? How did you start that ?

Angel Hsu: That’s a really great question. When I was working on my Ph.D., it was focused on the fact that for a very long time, environmental policy decisions and management were not based necessarily on information data or hard facts. A lot of it was based on hunches or ideas or theories about what we should do to address climate change or reduce air pollution. It just seemed like it was an an obvious gap. If you look at the business world and the private sector, they’re always thinking about what’s the bottom line. What are the key performance indicators or the KPIs so that we can measure success. But for the environment, that’s much harder to do. If you think about climate change, it happens on a 30 year cycle. And it’s really difficult to say, ‘well, I’m gonna implement this decision or this policy and I hope it to have this kind of outcome, and now I’m gonna go collect data to see if that happened.’ Because you’ve got to sometimes wait 5, 10, 20, even 30 years to know whether or not that’s happening.

The lab was founded to recognize the fact that also there are huge advantages in data and data science. You think about our smartphones and internets and now ChatGPT and these AI-driven chatbots are taking over our lives. We’re generating huge amounts of data. And so, the lab is really trying to think about how we can leverage this big data revolution specifically at this intersection of climate change and environmental policy.

Andrew Stuckey: Yeah, I read a book a few years ago about what the predicted future of the impact of artificial is. And obviously it was very hypothetical, but one of the takeaways was that most jobs were going to evolve into people managing the data that the AI is producing. There’s so much data that’s going to be available that it’s an overwhelming amount and we don’t know what to do with it. It sounds like this is like one of the steps toward addressing the amount of data that we’re going to have and how we process it. Do you feel like it’s been successful? Has it played out the way you thought it was going to?

Angel Hsu: I would say that it’s actually happening at a much faster rate than anyone could have ever predicted. When I was in college at Wake Forest University, we didn’t even have Google. I mean, Google literally did not exist. We were using AOL Messenger. There were still chat G’s or you’re asking this online butler questions about, ‘what is gravity?’ I teach classes on data science and climate change and the fact that they can Google answers to everything and about coding, about data and climate change, that’s really incredible.

Just in my own work, what we’ve been able to do is using these large amounts of data, answer questions and understand climate- and environment-related phenomenon that we would’ve never been able to do before. One example is the fact there is long been recognized disparities in exposure to different environmental pollutants and also temperature. That is tied back to a lot of policies that happened decades or hundreds of years ago for our relatives. To our great-great grandparents’ redlining policies, for example, that discriminated against black and minority populations from accessing loans that would’ve allowed them to be more mobile within cities. And so one question that we have asked using big data is are these patterns isolated? Is it just happening in a couple of cities where we’re seeing that people who are living or who have lived in historically red-line areas, are they exposed to higher levels of pollution and temperature? Or is it more widespread? And with satellite remote sensing data, these are sensors that regularly traverse the earth the same time every single day. We can then start to systematically use this data to analyze whether there are patterns, systemic disparities, and exposure to heat- and climate-related phenomenon.

Andrew Stuckey: I think most people listening would assume that the answer to that question is ‘yes.’ Is that what you’re finding in the data?

Angel Hsu: That was the hypothesis that we entered this research with. We know anecdotally and also other people have done research looking at disparities in air pollution. We know that some of these, these redlined more hazardous neighborhoods and districts throughout cities tend to be located to busy highways. And so I think anyone who has walked along a busy highway, you can smell that exhaust coming from cars and from trucks. Also, these populations could be located in areas next to landfills or to toxic waste facilities or to factories. In terms of temperature, there hasn’t been enough of this systematic analysis. We did have some inkling that we would see the same types of patterns of disparities, but we didn’t realize how widespread it was gonna be.

Using the satellite remote sensing data — because these sensors can measure land surface temperature above where people are living above cities — we actually found that in 97% of cities all across the U.S., people of color and people living below the poverty line are exposed to higher temperatures compared to their white and wealthier counterparts. I think that was surprising. I didn’t expect to see that it would happen not just in a couple of major cities… Chicago, Detroit, New York, Boston, where you have heard of there being discriminatory legacies and segregation. Something that was really surprising was even in smaller mid-tier cities in America, we also see the same patterns.

Andrew Stuckey: One of my favorite topics of conversation on here, particularly when we’re talking policy and academics, is how do we effectively communicate this to the public? In a way that affects some sort of meaningful change, particularly with the urgent nature of climate change conversations.

Angel Hsu: That’s the million dollar question: how do you get people interested, motivated, inspired to act on an issue like climate change? In the work that I do and also in the field that I study, we refer to it as a super wicked problem. And part of the reason why it’s super wicked is because we’re the ones causing the problem… and we also are trying to solve it. It’s hard because we have a tendency to irrationally discount the future. We think that, ‘Oh, in the future they’ll have better technology. They’ll have more money to deal with the problem of climate change. And I’d rather enjoy driving my SUV and living in my huge house and flying all over the place for extravagant vacations today.’ When you think about “Inconvenient Truth” and former Vice President Al Gore, when he started several decades ago talking about climate change and making it his political platform, the message was overwhelmingly negative. It’s like gloom and doom. The world is gonna end, its house is on fire. And I think very quickly we realized that that’s not the way to get people motivated to act on climate change. It’s actually very paralyzing.

Now, there are new words introduced in the dictionaries: this eco anxiety, climate change anxiety. These are new things that didn’t exist a couple years ago. Now, we’re realizing we have to flip the script and that’s exactly what the U.S. Inflation Reduction Act is trying to do. Let’s not use the sticks to punish people to punish polluters, but let’s actually give them carrots — think about financial incentives to get them excited about buying that e-bike, switching out their natural gas stove for an induction stove, getting that electric vehicle. Trying to be very positive and encourage people to act on climate change, instead of this gloom and doom narrative that has not really been that effective.

Andrew Stuckey: Obviously you can only speak from a limited perspective, but is there any sense that this is working? That changing of language and having these federal dollars available for things that are more pre-emptive, is there a sense in the scientific community that’s working? Or is it too early to tell yet?

Angel Hsu: I think in the U.S. context, because the IRA was just approved last year, we’re just now starting to see some of those dollars flow to local governments and to people. I have a friend, for example, who lives in Pennsylvania and she’s getting a new heat pump installed in her home. She said she was getting something like close to $8,000 in tax credits. I think we’re gonna start to see more of that trickle in the United States.

But I’m also one of the climate scientists that contributed to the assessment report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. This is an international body of close to 3,000 scientists, more than a hundred governments all around the world that surveys all of the scientific evidence. We try to distill it in an easy to understand way for people and to inform governments as to what they should do on climate change. I contributed specifically to Working Group Three on mitigation. It’s looking at what can we actually do to reduce our impact on climate change. And I can say: it is so positive in terms of looking at the evidence of what actually works. One chapter in particular that was added to the IPCC is all about demand side responses. What can we do as individuals to affect climate change?

What we found is… if people start driving our cars less, switching to electric vehicles, staying at home instead of going to the office every single day, eating less meat… then we can actually reduce emissions 40 to 70% across these different sectors. That’s the first time evidence has ever been put together from the scientific literature. That gives us a lot of encouragement and a lot of optimism that when we tackle climate change and we do things together in aggregate, we can really have an impact.

Andrew Stuckey: Is there anything you wanted to mention that we haven’t gotten to yet?

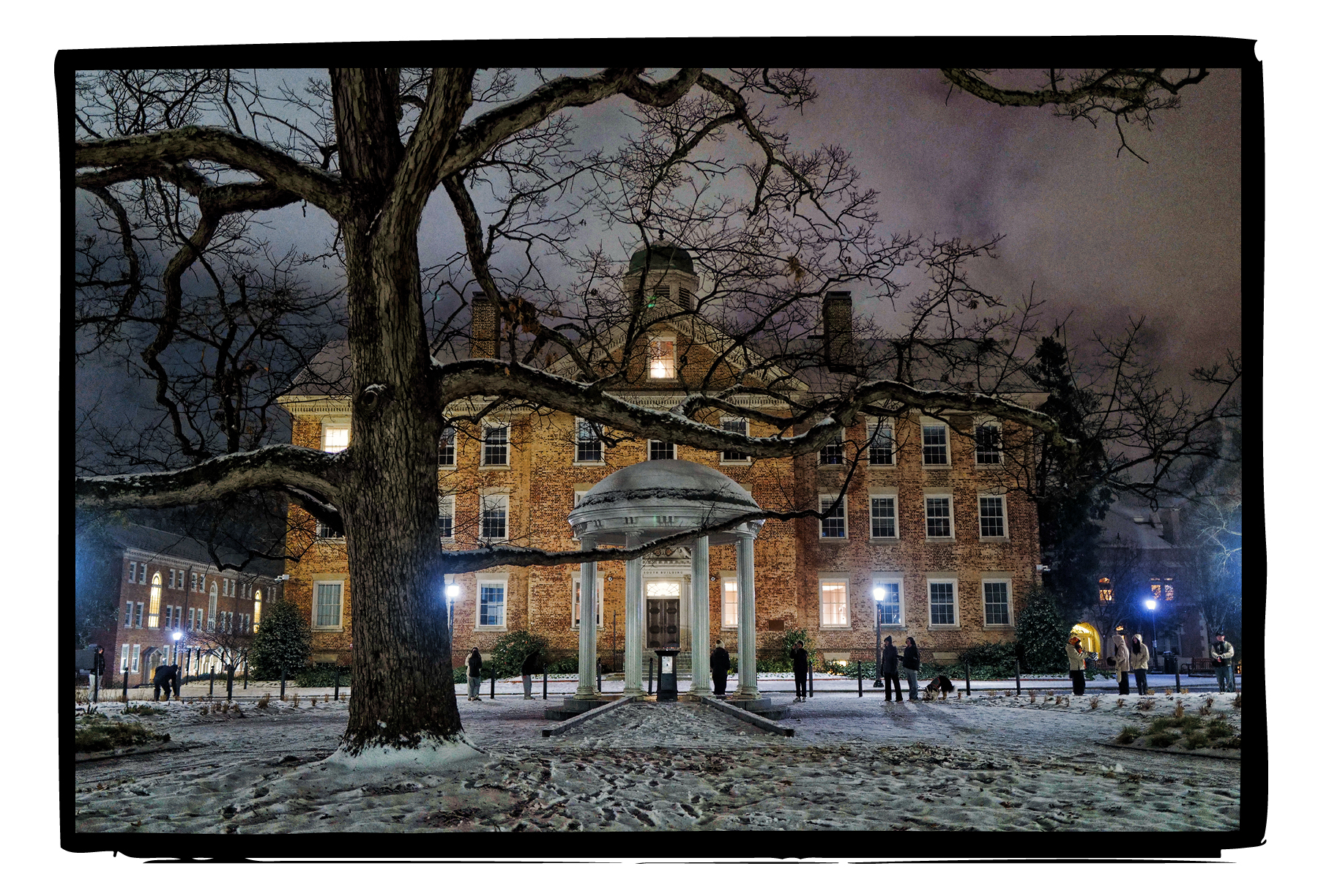

Angel Hsu: I’m a new transplant to the Triangle area, to Chapel Hill. I grew up in South Carolina and then I lived everywhere else. And I would say I’ve been really encouraged by what Chapel Hill and local governments have been doing and how welcoming they have been to a researcher. We have partnered with them to engage citizens on high resolution heat mapping. In the month of August 2021, we got 40 volunteers. We partnered with the Town of Chapel Hill, Museum of Life and Science in Durham, the Institute for Environment at UNC and the North Carolina State Climate Office to give citizens sensors. They were going around different neighborhoods in to get better data to understand what is the actual exposure of heat and temperature at the human scale. When you’re on the ground, you’re getting a lot of that main radiant temperature, that heat that’s bouncing off roads and buildings, from cars and air conditioners. It can be much different. That was a really great exercise and I was able to contact [people] right away. They were really responsive in partnering, so I’m really encouraged. It’s not easy because, of course, local governments can only do so much. They have to coordinate with the counties and also state level governments and national government as well. It’s really challenging, but I think that we’re heading in a in a good direction.

Photo via Angel Hsu/Twitter.

Chapelboro.com does not charge subscription fees, and you can directly support our efforts in local journalism here. Want more of what you see on Chapelboro? Let us bring free local news and community information to you by signing up for our biweekly newsletter.