Researchers at the University of North Carolina are working to perfect stem-cell research after a discovery made regarding glioblastoma, a cancerous brain tumor.

The research team from the UNC Eshelman School of Pharmacy has found that surgically removing these brain tumors causes cancer to grow 75 percent faster than before surgery.

Treatment of glioblastoma is typically a combination of surgery, chemotherapy, and radiation but varies from patient to patient. Because of the obtrusive nature of brain tumors, glioblastoma can not be fully removed during surgery, leaving a portion of the tumor behind.

The assistant professor in the UNC Eshelman School of Pharmacy who led the research, Shawn Hingtgen says that the remaing glioblastoma in the brain after surgery is fundamentally different from the original brain tumor.

“The process of removing the tumor speeds up the cancer such that we have to rethink of how to treat the disease differently after the surgery,” Hingtgen said.

Neuropathologist and associate professor at the UNC School of Medicine, Ryan Miller, says that current drugs are developed to treat large, solid tumors and do not accurately work on the residual brain tumors.

Hingtgen and his research team are working on a new stem-cell treatment that can hunt down and kill the cancer cells that are left behind when a brain tumor is surgically removed.

To more accurately test new treatment, a graduate student working in Hingten’s laboratory, Onyi Okolie, has developed a new mouse model of a brain with glioblastoma after surgery.

To do this, Okolie implants a tumor into the mouse’s brain and allows it to grow until it is comparable to when a human would begin having symptoms from the tumor such as headache, seizures or an altered mental state.

At that point 90 percent of the tumor is surgically removed from the mouse, which causes astrocytes, star-shaped glial cells, to secrete chemicals that trigger the remaning cancer cells to move and grow 75 percent faster than before.

The new model will help researchers better understand the effect of surgery on glioblastoma and could potencially lead to new therapeutic targets that will improve post-operative care.

The new findings are published in the journal Neuro-Oncology.

Related Stories

‹

UNC Study: 'Habitual' Social Media Use Changes Kids' Brain DevelopmentDo you remember the time before social media? For children and young adults, social media is a significant part of their lives — and we’re still learning how it’s affecting them.

A study conducted by UNC researchers found a habitual checking of social media can impact brain development in adolescents.

![]()

On Air Today: 'Naloxone Near Me,' with Delesha CarpenterAaron welcomes UNC's Delesha Carpenter to discuss "Naloxone Near Me," a new statewide initiative that could save lives.

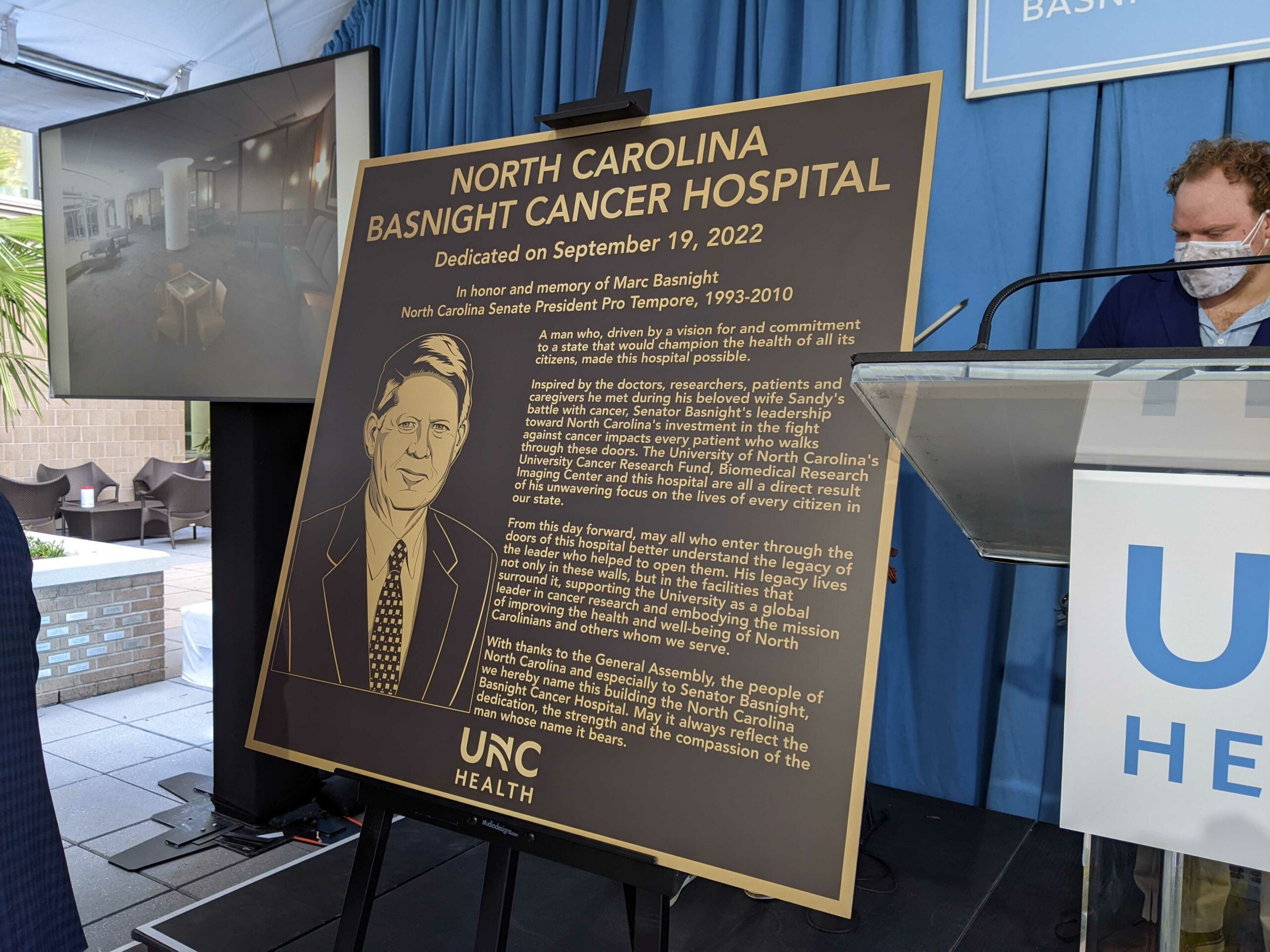

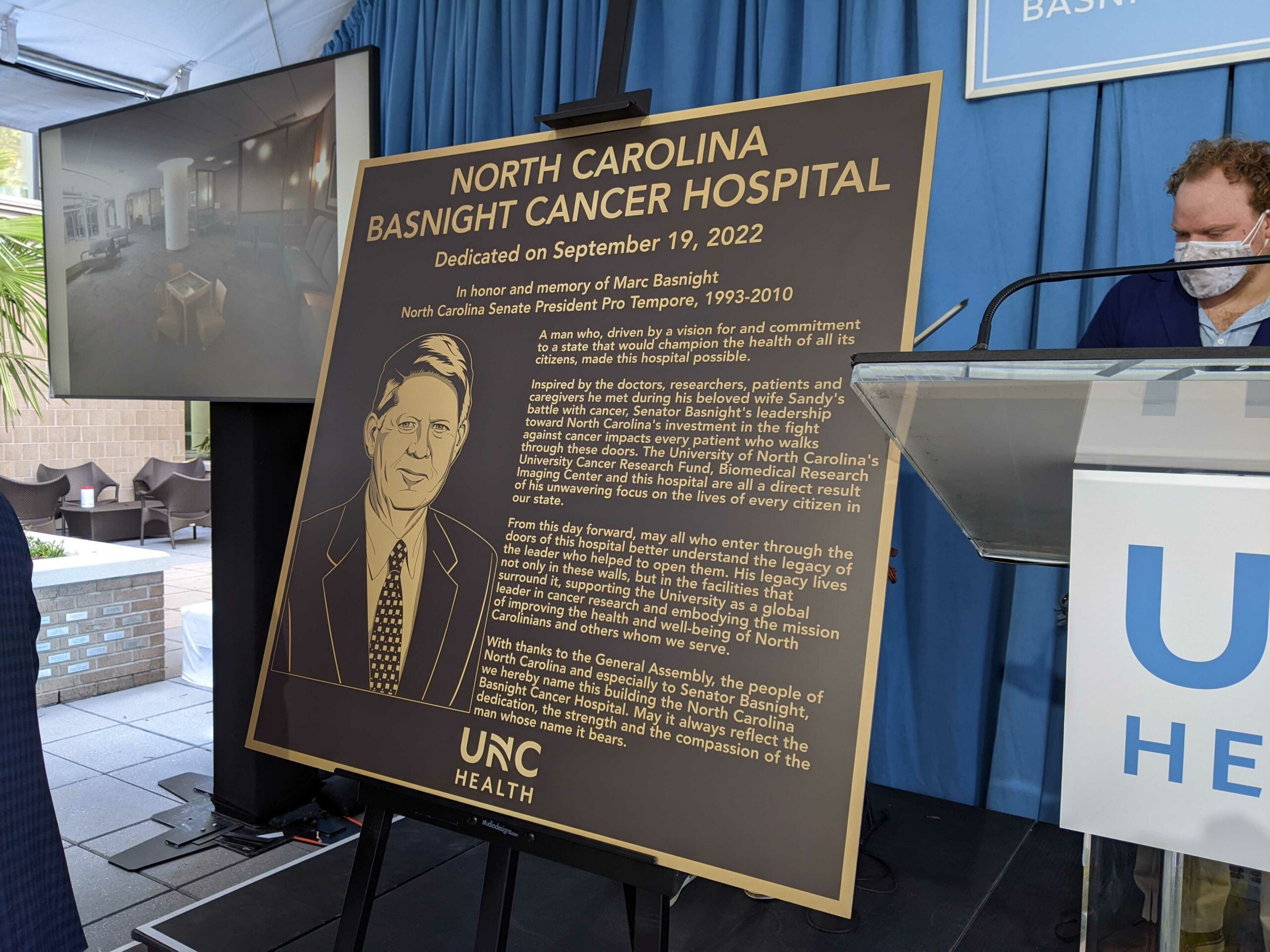

UNC Cancer Hospital Renamed to Honor State LeaderMarc Basnight was North Carolina’s longest-serving legislative leader. After his death, state legislatures wanted to find a way to honor him.

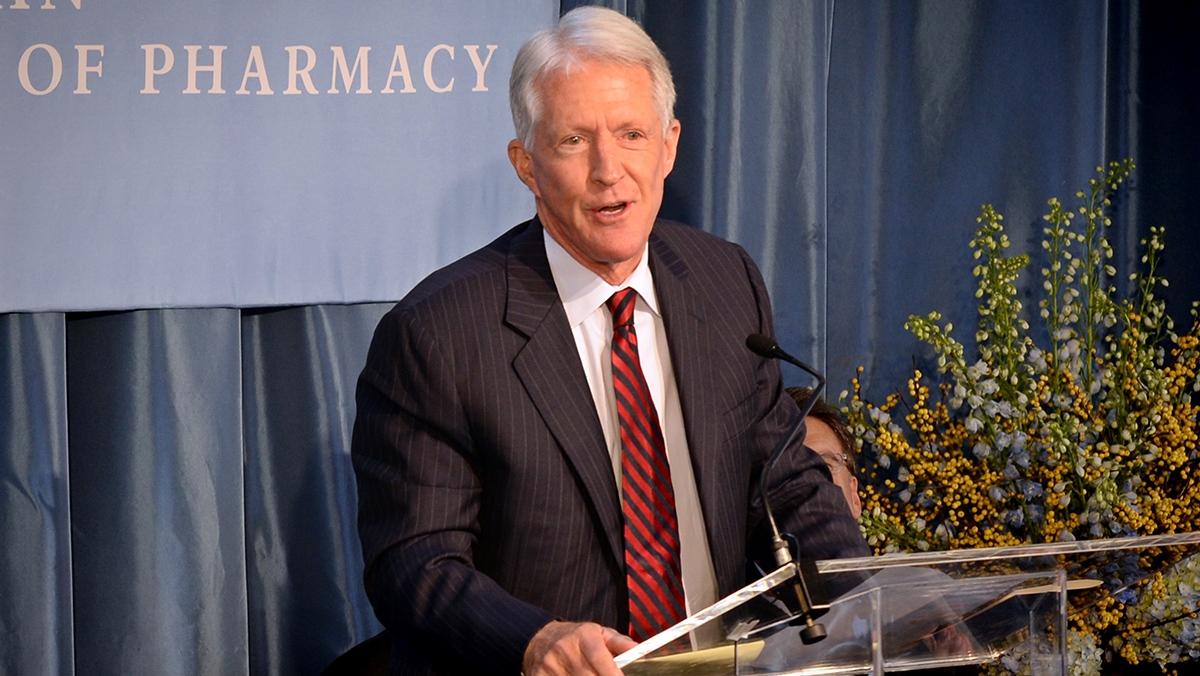

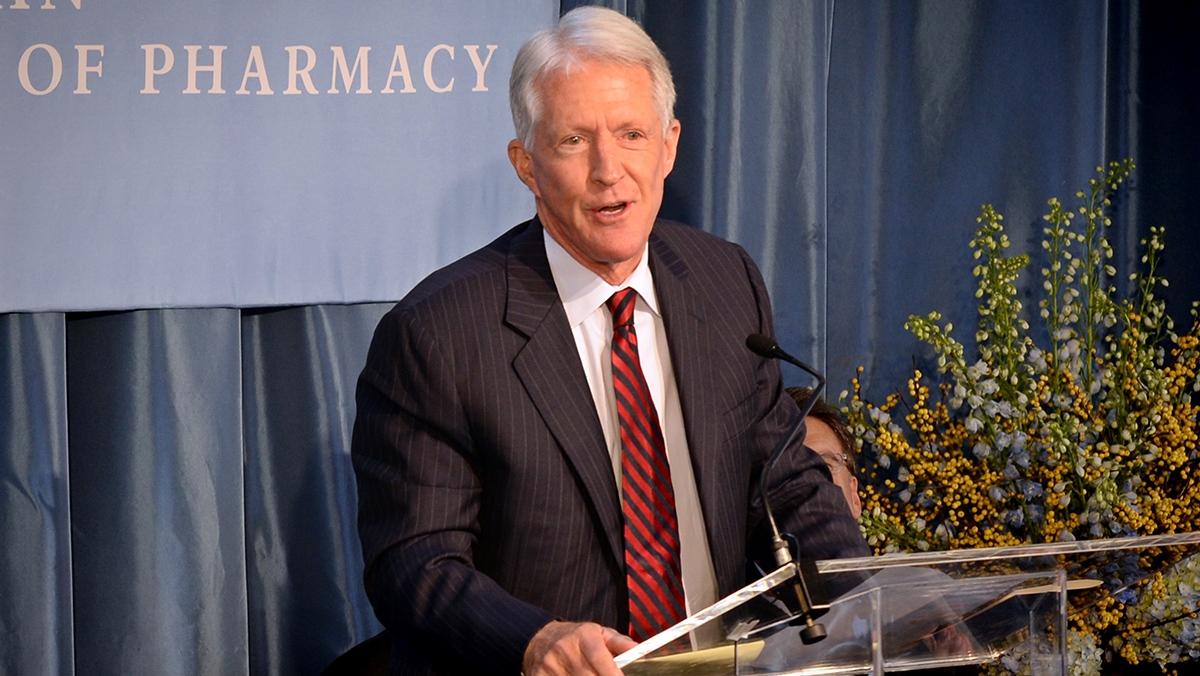

Namesake of UNC Pharmacy School Suing Pro-Trump Group Over Voter Fraud InvestigationThe namesake of the UNC Eshelman School of Pharmacy is in the news as he attempts to get back $2.5 million of donations he made to post-election investigations of voter fraud. Dr. Fred Eshelman, founder of companies that invest in private health care and develop new drugs, filed a lawsuit in Texas last week against […]

UNC Researcher on COVID, At-Risk Populations: 'We Are Not Out of the Woods'As coronavirus cases in North Carolina continue to rise, researchers and health officials are expressing concerns for at-risk groups – and that means more than just the elderly population. Dr. Giselle Corbie-Smith is a UNC Professor of Social Medicine, the Director of the Center of Health Equity Research and a Professor of Internal Medicine. She […]

UNC Schools, Morehead Planetarium Make Medical Supply DonationsThe North Carolina Department of Health and Human Services says it requested 500,000 each of N95 masks, gowns, gloves, face shields and coveralls from the federal stockpile to help health care workers be properly protected while treating patients. As of Sunday, all amounts of that PPE, or personal protective equipment, are less than requested. That’s […]

![]()

UNC Graduate Programs for Pharmacy, Nursing Earn Top National RankingsMany UNC graduate programs earned high marks in the U.S. News & World Report’s “Best Graduate Schools” list, including some taking the top rankings. The list’s latest results were shared by the university in a release on Tuesday, revealing the UNC Eshelman School of Pharmacy as the top graduate program in pharmacy for the second straight […]

UNC Pushes Back Against Research Allegations in The AthleticUNC interim chancellor Kevin Guskiewicz has long been viewed as one of the leading concussion researchers in the world in recent years. But a report published in The Athletic this week claimed that for years UNC student-athletes, particularly football players, were testing positive for ADHD at abnormally high rates – which the report claims could […]

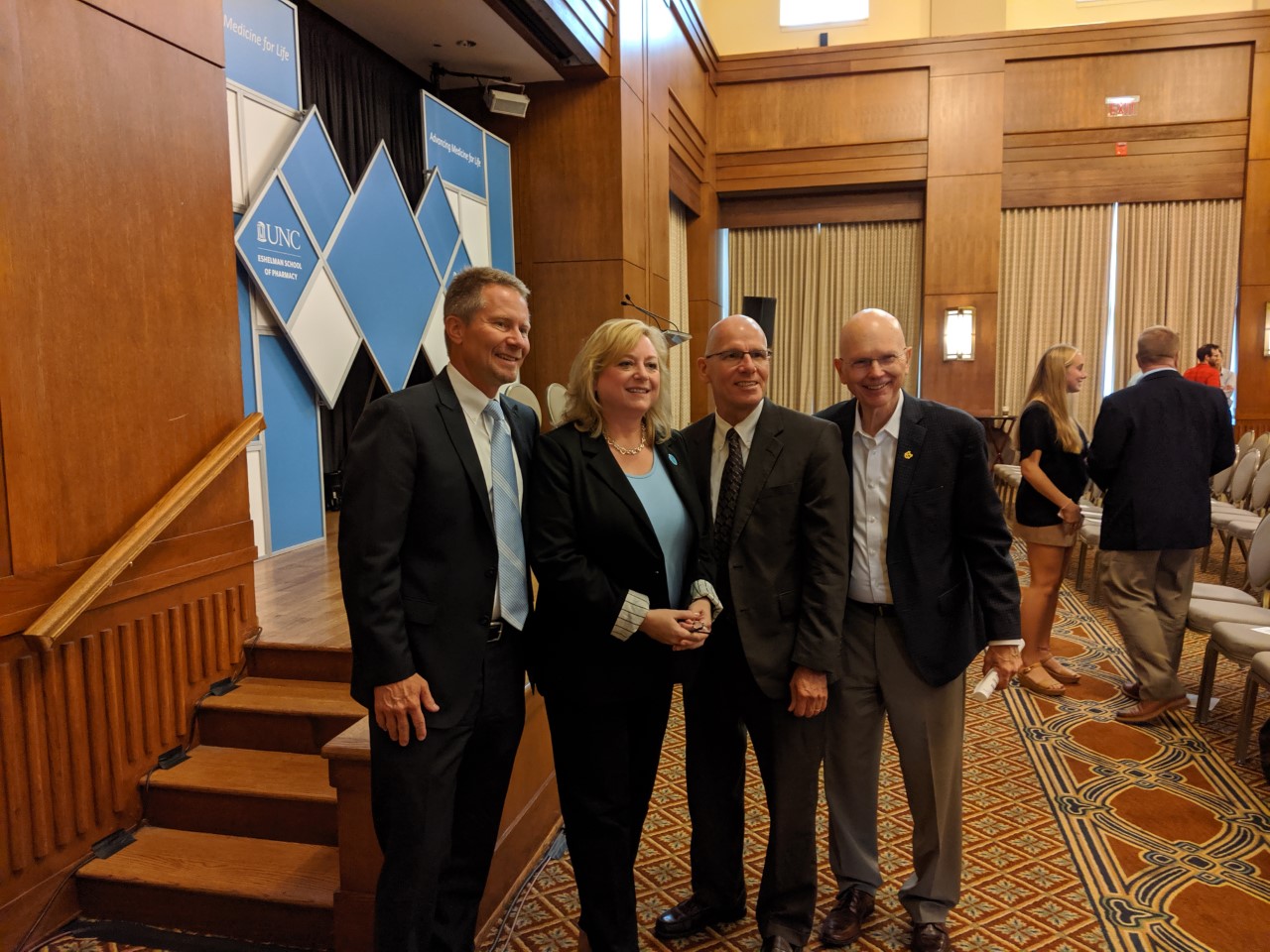

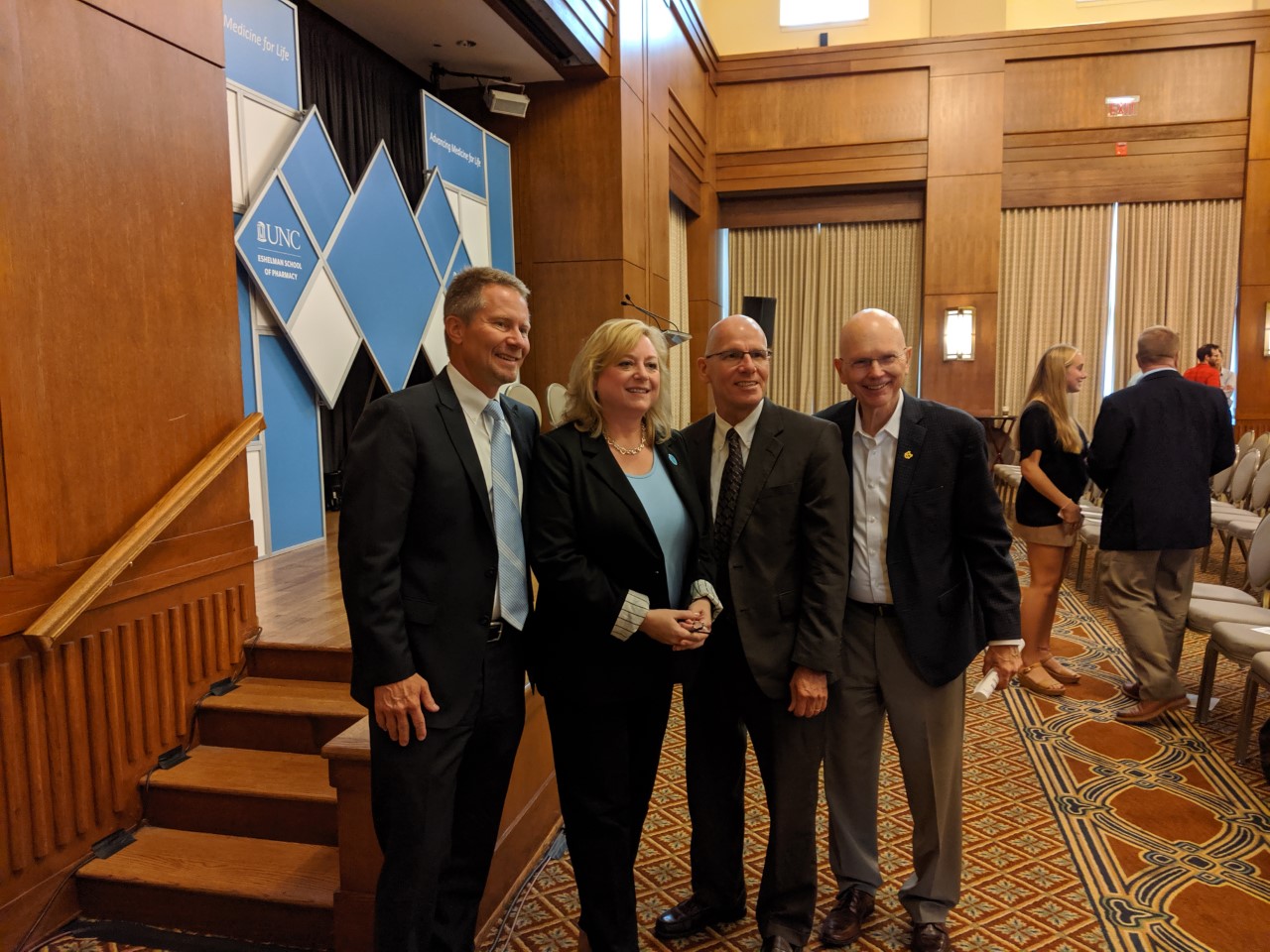

UNC School of Pharmacy's New Dean Begins TenureUNC’s Eshelman School of Pharmacy held a celebration on Tuesday to welcome its new dean to her job, as Angela Kashuba became the school’s eleventh dean. Kashuba was selected in May to take over as leader of the top pharmacy school in the nation. The permanent role had been vacant since Bob Blouin was hired as […]

New UNC Center to Research Technology's Impact on DemocracyUNC announced its plans for a new research center on Monday that will study the ways technology is changing democracy in the digital age. The Center for Information, Technology and Public Life will look to discover empirical numbers on ways technologies impact and interact with society. Topics like fake news, the sales of data to […]

›