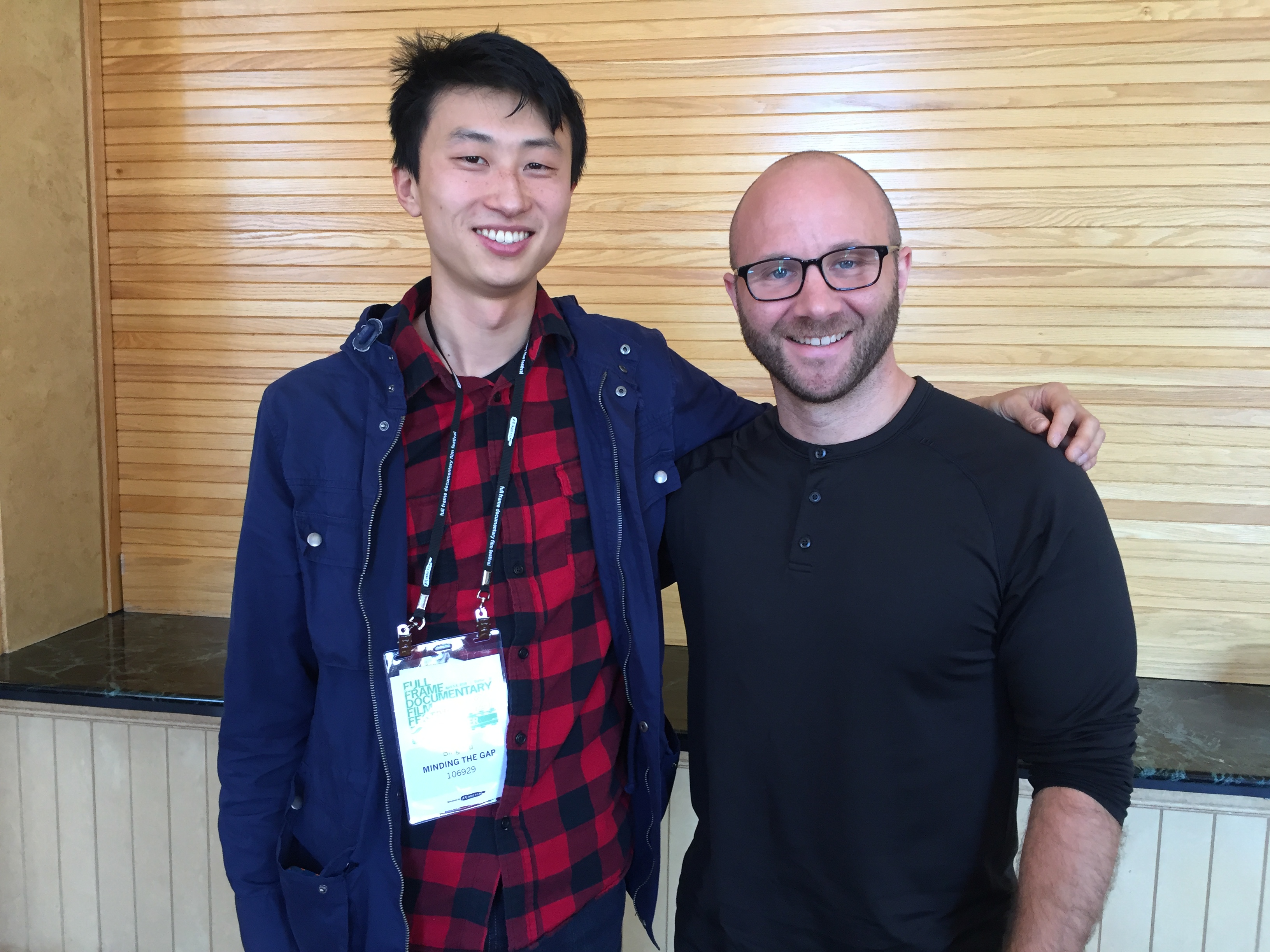

“Minding the Gap” director Bing Liu and Rain Bennett

I was excited to be back at Full Frame for the first time in years.

Since I’d moved back to North Carolina in 2014, I’d inevitably have some shoot scheduled for that first weekend in April and couldn’t attend the festival. I’d watch my friends and colleagues post pics on social media, having the times of their lives at one of the largest documentary film festivals in the world.

This year, I went alone with the intention of watching some of most talked about docs, hanging out with my filmmaking friends, and writing about the local experience of the festival.

And to me, that is the experience. Sure, there are big name filmmakers in town. Sure, some of the documentaries screened will be nominated for (and possibly win) Academy Awards. But en route to Sundance, Cannes, Toronto, IDFA, or SXSW, these films and filmmakers stop by our little Durham and shake up the city in a marvelous way.

Restaurants and bars have special deals, parties are scheduled all over downtown, and thousands of locals congregate to share the love and experience of untold real-life stories. Literally every stranger I sparked up a conversation with was from the Triangle. They had been coming for years — some for over a decade! They looked forward to the festival every year and told me their lives more enriched because of it.

I knew I wanted to write about what Full Frame Film Festival offers to these North Carolinians that are so loyal to it, but my story hadn’t quite emerged yet.

I saw some amazing films that I could write about for days, including the highly anticipated Three Identical Strangers and Won’t You Be My Neighbor? On Saturday afternoon, I rode my Limebike as fast as I could in the cold rain back to Carolina Theatre. People had said good things about Minding The Gap, the next movie I was to see, but I didn’t know a lot about it. To be honest, I saw it was about skateboarding friends and thought that would be a good break from the heaviness of films about politics, war, and suicide. Boy, was I in for a surprise.

My first reaction was to the way in which director Bing Liu shot the movement-based action of skateboarding as a “one-man-band.” As a filmmaker who has often had to shoot, produce, monitor audio, and lug gear for his projects, I quickly sympathized with his task and admired his approach. He ran (on foot!) beside the skaters with a Glidecam and stayed on a wide shot as they tore through the streets. The footage was smooth and gorgeous.

Then, I found myself bursting with laughter watching what could have so easily been my own friends on the screen — a group of rough-housing skaters that drank too much and bitched about their parents and their jobs. They’d slam their bodies down on the sidewalk, all with smiles that can only be known by people who have loved something so much they’d sacrifice their bodies every day just for the one glorious moment of unlocking a new move.

As the story unfolded, new parallels that I wasn’t prepared for emerged. The main characters, as well as the filmmaker (who was now a part of the narrative), were dealing with the insidious effects of childhood abuse as they neared adulthood. I had also been the child of an abusive father figure and felt my body shift from tingling of laughter to the lurking of fear.

I saw myself in those kids — all trying to navigate through the hidden obstacles they faced, both consciously and unconsciously. Eventually, they’d either have to face their trauma head-on, or face becoming the same monster that terrorized them.

It’s a struggle I know well. I left the theater feeling the weight in my heart.

I came home that night and my girlfriend Maya was writing out “Thank You” notes for the folks that had attended her recent baby shower. She asked me how the movie was.

“It was… it was amazing. But it was heavy. I’m still messed up by it.”

She listened as I talked about how closely it hit home (she’s knows my family’s story well), how it was so clear that we risk continuing these patterns unintentionally as we get older, and how I admired the director for inserting himself into the story, despite resisting it initially. I was inspired and excited and sad all at the same time.

I gave her a kiss and left to wash the dishes while she finished her notes. I didn’t clean one plate before I walked back into my office, put my hand on her shoulder and burst into tears.

“I’m not going to be like that with our baby.” I said.

She told me she knew I never would.

The next morning I met Bing, the director of Minding the Gap in the hospitality suite of the festival. He was wise and kind and spoke from the heart. I liked him immediately.

We talked about dealing with childhood abuse as an adult and how people can normalize abuse and not recognize the patterns even when they repeat themselves in the following generation. I told him how his film affected me and how I’d been through similar situations, but had been fighting hard to break that chain. We talked about why our mothers tended to downplay the abuse or pretend like it didn’t happen or wasn’t that bad.

Bing understood me and even educated me through his story.

“I set out with this idea that relationships with fathers was going to be a big theme; I didn’t expect that mothers and sons would become such a theme that’s mirrored as well.

There’s this defense from the mothers and that all figures into the cycle of violence. An abuser abuses someone, that person is hurt and wants to get away, then immediately after the abuser will apologize and try to win them back, and then there will be like a honeymoon period where it gets a little better and then it just builds up again. That’s the cycle of violence. What happens to the women in these situations is that they’re in love with someone who hurts them and they know that and it’s a form of control.

In a way, this project was like a big homework assignment outside of therapy. There’s certain things that help you formulate it into a bigger pattern and make you feel like you’re not alone.

A childhoods are so precious and that’s where we learn so many things that are invisible to us. We have these alarm systems. When you burn yourself on the stove as a kid, you automatically pull back. But when you experience things (like abuse) that aren’t normal in the household, your alarm system becomes faulty. And you grow up and never realize you have this alarm system in the first place. So when something triggers you, your body remembers that you had to do something as a child to react to that. You might turn into a different person to handle it. And your adult self is going to remember that.

I’m glad you reached out. I mean, that’s our goal with any of this, is to hope that it touches someone and reminds people that this is important.”

Then it dawned on me. This is what Full Frame provides North Carolinians with: the chance to meet people with similar experiences, discuss our different approaches, and figure out better methods to move forward as people on this planet together. We learn how to be better people.

Bing and I talked for 25 minutes until he had to rush off to the awards BBQ (where his film won the Audience Award!) and hop on a plane back to Chicago for a screening that night.

I went home that afternoon to rest before the closing night film, America to Me, but I did not make it back to the festival.

At 5pm, my girlfriend had her first contraction.

I will not repeat the cycle.