“Viewpoints” is a place on Chapelboro where local people are encouraged to share their unique perspectives on issues affecting our community. If you’d like to contribute a column on an issue you’re concerned about, interesting happenings around town, reflections on local life — or anything else — send a submission to viewpoints@wchl.com.

Courts Should Stake a Seminole Spear in FSU. The ACC’s Position Is Strong; FSU’s Position Is Lousy

A perspective from David McKenzie

David McKenzie is an attorney in the Raleigh-Durham-Chapel Hill area. He specializes in intellectual property law and can be reached at david@mckenzielaw.net.

This article explores the intricate legal battles between Florida State University (FSU) and the Atlantic Coast Conference (ACC), shedding light on FSU’s considerable challenges and the ACC’s robust legal standing in the lawsuits. Designed for accessibility, it provides a detailed breakdown of the pivotal intellectual property issues and contractual obligations that are at the forefront of these high-profile cases in Leon County, Florida (Tallahassee) and Mecklenburg County, North Carolina (Charlotte).

FSU v. The ACC (Leon County, FL)

1. FSU’s Misunderstanding of Copyright Law

FSU’s approach to challenging the Grant of Rights (GOR) ignores the key principles of copyright law. When FSU licensed its media rights to the ACC, it effectively agreed to specific terms regarding the use and control of these rights. The notion that FSU can retroactively challenge its agreement, because the financial rewards are now seen as unfavorable, reflects a misunderstanding of how copyright licensing works. Copyright law doesn’t provide an avenue for licensors to rescind their rights based solely on a change in market conditions or the realization that a deal is a bad one.

2. Failure to Acknowledge Voluntary Agreement

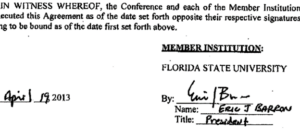

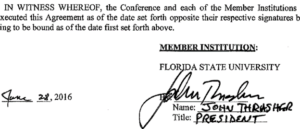

A fatal flaw in FSU’s Leon County lawsuit is its complete failure to acknowledge that the university willingly entered into the GOR, not once but twice. FSU not only agreed to the initial terms but also reaffirmed its commitment through a subsequent amendment. This casts serious doubt on any argument that any GOR is inherently unfair or one-sided. Additionally, there is no record of FSU proposing to return the millions it received under either GOR, which further detracts from any arguments of inequity. Although one might speculate about FSU’s ability to return the millions received, even if it desired to do so, the crucial point remains: the ACC holds two distinct contract signatures from two FSU presidents.

Florida State University President Eric Barron’s 2013 GOR Signature

Florida State University President John Thrasher’s 2016 GOR Signature

3. Lack of Valid Contractual Defenses

FSU’s complaint largely hinges on the claim that the GOR is a bad deal. However, merely entering into a bad deal is not a valid ground for voiding a contract. Completely absent from FSU’s complaint are traditional contract defenses such as fraud, duress, or misrepresentation, which are typically required to challenge the validity of a contract. (See Fn. 1, below.)

4. Over Reliance on Antitrust Arguments

FSU’s lawsuit heavily relies on the premise that the GOR and its associated penalties violate antitrust laws. But antitrust laws are designed to protect competition from harmful monopolies and unfair business practices, not shield parties from bad deals made with full knowledge and consent. FSU’s complaint in Florida primarily revolves around regret over a deal that has become financially less favorable over time— that is, it’s just a bad deal, and competition is not harmed despite FSU’s regret.

Moreover, state antitrust laws cannot override the well-established principles of federal copyright law. Indeed, FSU’s antitrust position flatly disregards the robustness of federal copyright law, which firmly governs the terms of the GOR as a copyright license. By invoking state antitrust complaints, FSU is not just reaching for an unlikely legal remedy; it is misapplying these laws in a context where they are arguably irrelevant. Ultimately, FSU’s emphasis on antitrust arguments may be a diversionary tactic, possibly aimed at shifting focus away from the more challenging task of proving traditional contract defenses.

Ironically, FSU does not challenge the inherently anticompetitive system of collegiate athletics itself – which on its face is an exceedingly closed system of competition – where schools like Appalachian State and East Carolina have near-impossible odds at joining a major conference like the ACC, a practice which arguably violates the very antitrust principles FSU now invokes.

Here, FSU’s state school brethren in University of South Florida, Florida International University, Florida Atlantic University, and the University of Central Florida should take keen notice of the state statutory construction FSU now employs. If FSU can use Florida antitrust law to bust out of the ACC on Florida antitrust grounds, then, following FSU’s logic, UCF, FAU, FIU, and USF should be allowed to burst into it. What is good for a Florida goose is also good for a Florida gander, after all. (See Fn. 2, below.)

5. What About the Exit Fee?

I harbor deep skepticism about Florida State University’s calculation of its exit fee from the ACC. FSU’s legal strategy inflates this fee by amalgamating the value of media rights pledged (not forfeited) under the GOR with unreimbursed broadcast fees and a genuine exit fee. That’s $130 million (exit fee) plus $13 million (broadcast fees) plus an estimated $429 million (media rights). The total, a staggering $572 million, misleadingly conflates separate contractual elements, and is an obvious attempt to take what is fundamentally a question of intellectual property licensing and supplant it with one having to do with antitrust law.

Intellectual property holders commonly assign rights like copyrights, trademarks, and patents for specific durations and fees. This inherent value within the deal never translates to an “exit fee.” It’s just the value of the deal. To construe the pledged intellectual property, valued at $429 million, as a penalty in contract is not only legally unsound but could also severely damage FSU’s credibility as a reliable party in future licensing agreements. If market conditions dictate the terms of an IP license, no one would risk entering an agreement with FSU, fearing arbitrary redefinitions of contract terms based on FSU’s displeasure in a change in market conditions and the money FSU was receiving. Ask Disney, Netflix, Fox, WRAL, or any entertainment provider, and it will tell you that is not how IP licensing works.

Better yet, imagine buying two Taylor Swift tickets, one for last year and one for next, where you pay the same amount for both to secure your spot at both stadiums. Now picture Taylor, after taking your money, suddenly throwing a tantrum and threatening to skip next year’s show because ticket prices for, say, Beyoncé goes up. Now imagine Taylor, after accepting your payment and not offering to give any money back, unilaterally demanding a steep price hike for next year’s performance. Your gut response of “that’s absurd” is justifiable. But that is essentially what FSU is trying to do with the GOR and the exit fee— reneging on a previous agreement based on buyer’s remorse, not antitrust law, and because of a change in market conditions.

As for the actual exit fee of $130 million, this figure, contrary to being excessive, is probably fair. It likely accurately reflects, if not underestimates, the real economic impact and loss the ACC and its member institutions would suffer from FSU’s departure. Liquidated damages, though required to reflect actual damages and not act as a penalty, in this case seem within a reasonable estimation of the ACC’s losses.

All in all, FSU’s lawsuit against the ACC appears to be more about escaping a bad deal than addressing clear-cut legal violations. It shows a misunderstanding of copyright law, lacks any meaningful contract defenses, and makes strained antitrust arguments. FSU may have a conceivable beef with the raw exit fee, not the money tied to the GOR (an entirely separate issue tied to licensed intellectual property as opposed to a contract penalty), but I would not encourage anyone to think that FSU has a strong case.

ACC v. FSU (Mecklenburg County, NC)

Conversely, I think this case is pretty strong, especially in the context of the ACC’s equitable claims. Let’s start with the basics.

- Basic Contract Law

The ACC’s entire complaint hinges on the principle that FSU, by virtue of its long-term membership, has reaped substantial benefits from the ACC. By now attempting to breach the agreements it willingly entered into, not once but twice, FSU is contravening its foundational commitments that have underpinned its relationship with the ACC for over 30 years. This is a pretty basic contract law.

2. ACC’s View of the Grant of Rights

While here I could go on for pages, and while I acknowledge the ACC does not say as much in its amended complaint, the GOR is about intellectual property, plain and simple, and IP is something that can be licensed and pledged just like any property we hold or sell.

FSU committed its intellectual property to the ACC to be exploited, and there is no mechanism under the Copyright Act to simply withdraw a copyright license because of a change in market conditions. (There actually is an obscure but meaningful exception here, but it pertains to the transfer of an author’s copyright that wasn’t a work for hire and is only applicable after 35 years from the date of transfer (17 U.S.C. § 203). If Congress intended to make a similar exception for a GOR in college football, it would have done so. By my count, we are in year eight.)

Otherwise, the ACC does complain that FSU’s commitment to the GOR first in 2013 and then again in 2016 allowed the ACC to negotiate more effectively with media partners like ESPN. It was a communal approach FSU agreed to. This collective approach, as opposed to individual negotiations by each member, led to the creation of the ACC Network, providing a stable and enhanced revenue stream to all members, including Florida State University. FSU’s participation in this agreement was a strategic move to maximize its media revenues. It can’t invalidate the GOR or, especially, yank its IP simply because, now, it realizes it entered a bad deal. Put simply, that is not how the Copyright Act or basic contracting works.

3. Acceptance, and Then Breach

By explicitly agreeing to the GOR’s “irrevocable” and “exclusive” terms, not once but twice, FSU entered a binding contractual commitment with the ACC. Through both its Leon County lawsuit and the actions of its Board of Trustees, the ACC argues that FSU has demonstrably contradicted its previous acceptance of these terms and the substantial financial benefits it has received, including increased TV revenue and ACC Network access. This constitutes a material breach of the contract, as FSU’s actions directly undermine the ACC’s reliance on its commitment and threaten the stability of the conference. The ACC’s lawsuit seeks to hold FSU accountable for this breach and ensure the continued enforcement of the mutually agreed-upon terms.

4. Equitable Estoppel and Waiver

This is the ACC’s best argument. This principle prevents a party from repudiating an agreement if they have previously accepted and enjoyed its benefits. In the ACC’s case, the conference asserts with merit that FSU has amassed millions in additional revenue under the GORs, including increased TV exposure through the ACC Network. The ACC argues that FSU, having banked substantial financial gains, is estopped from challenging the GOR’s validity. Here, the ACC has exposed FSU’s glaring hypocrisy. FSU’s actions are not just contractually untenable, but also fundamentally unjust if not also outrageous, given its prior acceptance and profiting from the very terms they are now contesting.

FSU’s challenge to the GOR, after more than a decade of enjoying its benefits, blatantly undermines the cornerstone principle of good faith in contractual relationships. FSU may not like the amount of money it has received, but that is no grounds to invalidate a contract, especially when FSU has already taken the money.

The Conspicuous Silence of Other ACC Members: A Calculated Caution

The conspicuous absence of any other ACC school joining FSU’s legal battle against the ACC is highly revealing. Despite rumors of pre-lawsuit discussions among several prominent members, including Miami, Clemson, UNC, NC State, Virginia, Virginia Tech, and FSU itself, not one has followed FSU into a courtroom. The reason likely stems from a comprehensive legal analysis conducted by every ACC institution, leading to a recognition of the ACC’s strong legal position and the risks inherent in FSU’s approach. Choosing pragmatism, the other ACC schools benefit from sitting back and watching FSU’s gamble, opting for stability over legal skirmishes.

Practical Considerations

1. Preemptive Strike: The ACC’s Legal Chess Move Against FSU

The ACC’s decision to file its lawsuit against FSU one day before FSU’s own filing (December 21, 2023, vs. December 22, 2023) was a tactical move. It was not just reactive; it was prescient and strategic. The original discussions, negotiations, and crucial signings of the legally-binding Grant of Rights all took place in North Carolina. This detail alone creates a strong argument that any disputes arising under the GOR should be interpreted under North Carolina law and be resolved in its courts. This is particularly relevant when, as here, there is an absence of a specific jurisdiction and venue clause.

Furthermore, the ACC filed first because there is a “first to file” principle in the law that stands for the proposition that he who files first, gets to go first. Though this principle does not guarantee priority, it does allow the ACC to make the argument.

Also, filing an amended lawsuit is standard practice, especially within the first 30 days. Here, I do not for a second believe, as some have suggested, that the ACC had its lawsuit prepared and “ready to go” against Florida State. I have ample experience in preparing lawsuits, and if you look at the ACC’s initial complaint, it is quite good but neither great nor thorough. I am guessing the ACC’s lawyers cracked it out in a day or two with every expectation of amending and after receiving short notice of FSU’s plan to sue the ACC. The amended complaint, filed on January 19, 2024, is both great and thorough. It showcases the full strength of the ACC’s legal team, introduces compelling new arguments, bolsters claims with additional evidence, and refines the ACC’s approach.

2. What’s Next in the FSU vs. ACC Legal Battle

It would strain a reader’s credulity for this article to affirmatively predict what will happen next. I don’t know. Yet, there are some guesses to be made.

Practically, the Leon County, Florida, court should stay the proceedings in deference to the case pending in Mecklenburg County, North Carolina. The pivotal events and signings related to the GOR happened in North Carolina, making it a more appropriate venue. Moreover, FSU can raise all its arguments, including antitrust claims, in a North Carolina court. While not dispositive or even predictive, the ACC did file first, and the “first to file” rule slightly militates in favor of the ACC’s case having priority.

Still, FSU’s lawsuit appears fundamentally weak. Its voluntary signing of the GOR twice, the financial benefits it reaped from these agreements, and the lack of substantial contract defenses manifest a remarkably weak position. This combination of factors might render FSU’s complaint so inadequate to warrant dismissal under Rule 12(b)(6) for failing to state a cognizable claim for relief.

Meanwhile, the ACC’s case, on the other hand, seems robust, particularly regarding the claims of equitable estoppel and waiver. These legal principles appear to form a formidable barrier to FSU’s attempts to challenge the GOR agreements it previously agreed to and benefited from.

Otherwise, my extensive experience in intellectual property law leads me to firmly believe that the Grant of Rights is a copyright license and not a restraint on trade. (I am not making this up; the GOR literally has a detailed “Copyright and License” section.) FSU’s attempt to reframe it as an exit fee and raise antitrust concerns directly undermines the fundamental principles of intellectual property licensing and should not be permitted. The success of intellectual property licensing hinges on the stability and predictability of legal agreements, which FSU’s arguments directly threaten to disrupt.

Moreover, Florida’s statutory antitrust law cannot override the provisions of the Copyright Act, which governs rights such as public performance– a central issue in this case. The specific rights and mechanisms for the ownership, transfer, and licensing of copyrights under federal law (e.g., 17 U.S.C. §§ 106, 201) must be considered.

Finally, while outside the scope of my legal expertise, it’s evident that business dynamics, particularly ESPN’s role, may resolve this dispute. ESPN currently benefits from a favorable deal providing extensive content at a good value. Any decision to alter the existing arrangements with the ACC would likely be driven by the prospect of securing an even more advantageous deal with major college football players. However, such moves would have to navigate complex and, here, legitimate antitrust considerations, especially for smaller schools seeking greater access to lucrative media deals.

Put simply, while legal factors heavily favor the ACC, the ultimate resolution of this dispute may well be influenced by business considerations, particularly the actions of major broadcasters like ESPN. The unfolding of this saga will be crucial not only for FSU and the ACC but also for the broader landscape of college athletics and media rights.

——-

Fn. 1: While FSU’s lawsuit does include a “Frustration of Contractual Purpose” claim, it is presented in a highly conclusory manner without substantive elaboration or application of fact to law. Such a defense typically applies in scenarios of nonperformance, inability to perform, or when unforeseen events drastically alter the essence of a contract, rendering performance meaningless for one party. In the case of FSU and the ACC, there has been no inability to perform under the GOR, and unforeseen events have not rendered FSU’s performance worthless. On the contrary, despite it being less financially advantageous compared to other conferences, the GOR has not been “worthless.” FSU has indeed derived considerable value, amounting to millions, from the agreement. Therefore, the invocation of “frustration of purpose” in this context is intellectually untenable, meriting no further discussion beyond this footnote.

Fn. 2: To this point regarding the interplay between antitrust and copyright, there is a giant elephant in the room, and that is copyright preemption. Essentially, copyright preemption means that state laws, including Florida’s antitrust statutes, cannot grant or enforce rights that fall within the scope of federal copyright law. 17 U.S.C. § 301. In the context of FSU’s case in Leon County, where the ownership and public performance rights of football games are being challenged under state antitrust law, copyright preemption becomes significant. If FSU’s arguments hinge on rights that are fundamentally copyright issues, such as the right to publicly perform the football games, then these arguments might be superseded by federal copyright law. This preemption would suggest that the Leon County court is not the appropriate venue for deciding issues that are essentially governed by federal copyright law. Thus, the case would require analysis under federal statutes and potentially be moved to a federal court with the proper jurisdiction to handle copyright disputes. This issue is altogether worthy of an entirely separate article.

Also worthy of a separate article are the claims that ESPN and, say, Wake Forest, as intended third-party beneficiaries of the GOR, have against Florida State. Both could suffer significant damages by way of FSU’s antics. This is particularly true for Wake Forest, whose financial stability could be dramatically impacted if FSU’s actions leave it dangling in Winston-Salem. The same is true for other ACC schools, but Wake Forest’s damages would be astronomical.

“Viewpoints” on Chapelboro is a recurring series of community-submitted opinion columns. All thoughts, ideas, opinions and expressions in this series are those of the author, and do not reflect the work or reporting of 97.9 The Hill and Chapelboro.com.