In the spring of 2020, everything changed.

Everything changed first over COVID-19. People worked from home, others lost their jobs. Overnight, our plans changed. Our needs changed. And the organizations we counted on to meet those needs – they had to change as well.

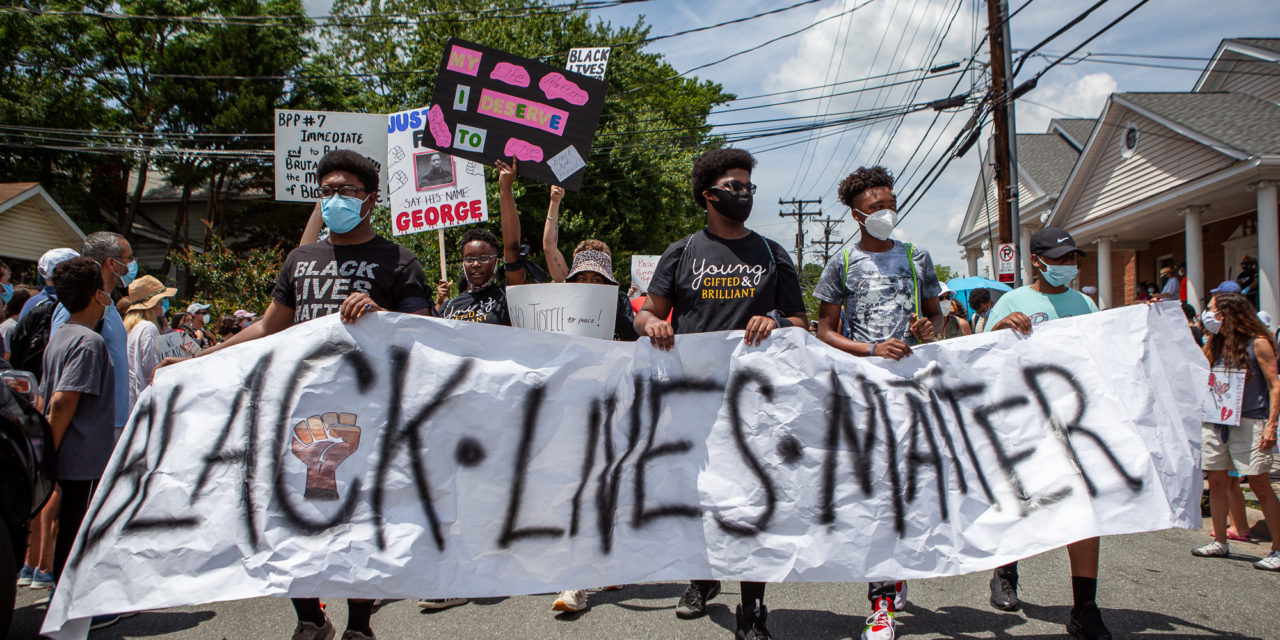

And something else was happening too. The same week North Carolina closed its schools, a woman named Breonna Taylor was shot and killed by police in Louisville. Two months later, George Floyd was killed in Minneapolis. And as people flooded the streets in protest, once again, we realized things had to change.

It’s now been three years since that spring. What have we learned from our experience? What lessons have we taken away? What changes have we made? And which of those changes will last?

“Three Years” is a series by 97.9 The Hill’s Aaron Keck – looking back on our memories and lessons learned from our collective experience, drawn from conversations with numerous government officials, nonprofit heads, scholars and thought leaders in the Chapel Hill-Carrboro community.

Click here for the entire 15-part series.

Listen to Chapter 6:

Chapter 6: The Police

“All of us in this career have a passion,” says Lt. Bubba Whitehurst of the Orange County Sheriff’s Office. “We get into this career because we want to help people.”

There are half a dozen law enforcement agencies in Orange County alone, all staffed with good people committed to public service. But the police killings of Breonna Taylor and George Floyd in 2020 were a stark reminder: that law enforcement is not perfect; that there are persisting racial disparities; that mistakes and bad judgments can be deadly; and that those deadly incidents can happen anywhere – including here.

“I don’t care how good your police department is, (or) how well respected and well connected you are,” says Chris Blue, who was Chapel Hill’s police chief in 2020. “When you see something like that happen, you know that your community is going to look at you a little differently.”

COVID-19 had already made us throw out all our old routines and standard procedures. So what better time to look in the mirror and ask: are we doing our jobs as well as we possibly can? Are we overlooking something, leaving someone out? Can we do better? And how do we get there?

Those were good questions for all of us, in every profession. But with protests swelling across the nation, there was a particular urgency when it came to law enforcement.

“We know we have a very dedicated public service department,” says Chapel Hill Mayor Pam Hemminger. “We have the only crisis unit in the state. How do we know, though, that this couldn’t happen here? You know, we guess it couldn’t, and we want it not to. But how do we know?”

While other communities saw backlash against the protests and a pushback against reform, in Chapel Hill the town took steps immediately.

“We decided to back off on random traffic stops,” says Hemminger. “We could show the numbers: it was more people of color that were being stopped, (for example) for their taillight being out, things (that) usually meant that people didn’t have the wherewithal to get it fixed. And giving them a ticket just adds onto it. So we stopped that – and we’re not seeing any increase in crime, from not doing traffic stops.”

And that change was only the start of a much larger conversation.

“Within weeks of George Floyd’s murder, our Town Council pulled together a task force of engaged community members,” Blue says. “They spent a whole lot of their time being very thoughtful about what we want safety in our communities to really look like.”

“We purposely went for folks who aren’t our normal people who volunteer for boards and commissions, but who had been through the system, who had been treated inequitably,” Hemminger adds. “They really came up with some great recommendations.”

Twenty-eight recommendations in all, many of them focusing on ways to reduce the role of police and divert more people away from the criminal justice system.

Read the Re-Imagining Community Safety Task Force report.

“The murder of George Floyd, and the (conversation) that resulted, gave legs even more to this idea that – let’s try very hard to keep the cops focused on what they’re good at, and let’s make sure the people who are in need of services in our community get services from the people who are best equipped to deliver them,” Blue says. “Police maybe could do less. Certainly some of the folks who receive our services are better off with a different service provider, (versus) a cop showing up.”

I tell Blue I’d had my own moment of clarity in the midst of that conversation: that we have a specific agency to respond when there’s a fire, and a specific agency to respond when there’s a medical emergency – but for every other emergency, regardless of its nature, you end up sending the police. That seems incorrect.

“What can we do to make that better?” I ask.

“It requires a community commitment to funding mental health,” he says. “I’m talking about on-the-ground mental health providers, who can go out into the field. And this is a longer term proposition, but it’s essential: when that mental health provider goes out into the field and find someone who needs wraparound resources, or when the cop encounters somebody at 3 A.M. who needs some help, but they don’t need handcuffs – what do you do with them? Where do you take them? The ER is not always the right answer, and the shelter is not always the right answer, but those are about the only options we have.

“So people often end up in places where they’re not best served – at the hands of the police, who are not always the best answer to their problem. I have great confidence in all our (local) law enforcement officers, but you know, you got to apply the right tool to the job, and we’re not always the right tool.”

Why was it easier for Chapel Hill to have that conversation about the role of policing? Maybe partly because that introspective approach was already there inside the department. Chris Blue points to Chapel Hill’s crisis unit: social workers inside the police department, who can respond to calls and connect people with needed services.

Many protesters across the country were calling for just that approach – but Chapel Hill has had that unit in place since 1973. It’s the only one like it in the state.

“Many of our philosophies are informed by this resource,” Blue says. “Our crisis unit members go on calls with us all the time. They sit in our staff meetings, they sit in our debriefs. They’re part of our planning team when we are thinking about large scale events. And that brings a different point of view to how we think about our work.”

The more I listen, the more I start to think: maybe we shouldn’t conceive of policing as separate from social work. Maybe policing, when it’s done right, is a form of social work – highly specialized, with unique training and specific skills, but a form of social work nonetheless. As Bubba Whitehurst said, police officers get into the business to help people – and when police are at their best, that’s what they do. I think about the officers who helped talk down a suicidal person on MLK Boulevard in the summer of 2020. I think about the officers in Hillsborough a few years earlier, who caught a woman stealing food to feed her hungry kids and responded by buying her two carloads of groceries. That’s social-work activity. And those are the stories we so often tell, when we talk about the positive role of law enforcement.

And in the summer of 2020, the question became even more urgent. What would it take – as Chapel Hill’s task force suggested – to “reimagine community safety” in that way? Over and above the standard law enforcement training, what else do police officers need to know?

“I think number one, you need to have compassion,” says Blue. “People don’t call 911 when they’re having a good day. They don’t call 911 when they don’t need help. They call when they do need help…

“How we respond, the way we respond, that comes all the way down to where we park our police car. And: do we make a lot of noise when we show up? Do we have a lot of lights going? Sometimes that’s appropriate. Sometimes it’s not. Sometimes it actually makes the situation worse. By your very presence in a uniform with a badge and a gun, you change the tenor of that interaction. And so some fundamental appreciation of that, the responsibility that goes along with that, is fundamentally important.”

State Rep. Renee Price was a county commissioner in 2020 – and she knows this question intimately, as her father was the first Black police officer in the history of Rochester, New York.

“My dad took the initiative to learn more about society,” she remembers. “He even took English literature. He would hand his books over to me and say, you need to read this book! But (he’d also read) books on Malcolm X, and ‘Soul on Ice.’ Taking the time to learn more, to expand your knowledge, so that you know people and you know how to work with people. Rochester was very, very diverse. You had all different languages and you had to know people, what their culture is.

“And you know, that’s another reason why it’s important for law enforcement to be a part of the community,” she continues. “So you’re not just policing a neighborhood, you’re actually protecting.”

The killing of George Floyd, and Breonna Taylor before him, drove home the need to re-examine the role of law enforcement: not just the policies and the outcomes, but its basic philosophy. Many communities resisted. But at least in Chapel Hill, Chris Blue says, the right conversations are taking place.

“Policing has been changing a lot the last few years,” he says, “and it needs to change. And I think the murder of George Floyd helped move that needle. Some. Not enough, quite honestly. And in many communities not at all, sadly. But I can tell you – it’s always the case, but it’s particularly the case now – we’re listening.”

But while law enforcement has drawn a lot of the attention, Renee Price says it’s not just police who have to look in the mirror – it’s all of us.

“Whether we’re talking about law enforcement, or teachers, or businessmen: if you’re brought up in a monoculture neighborhood, then when you get out into the general public, that comes with you,” she says. “Yes, we (need) better training for law enforcement – but we also have to look at society as a whole.”

Click here for the entire 15-part series.

Featured photo: a Black Lives Matter rally on Franklin Street, on June 6, 2020. (Photo by Dakota Moyer.)

Chapelboro.com does not charge subscription fees, and you can directly support our efforts in local journalism here. Want more of what you see on Chapelboro? Let us bring free local news and community information to you by signing up for our biweekly newsletter.