Movies are finding new ways to reach their audience as COVID-19 keeps audiences away from the big screen during what would normally be summer blockbuster season. “Greyhound,” a seafaring war movie set during WWII’s “Battle of The Atlantic” circa 1942, starring Tom Hanks (who also wrote the screenplay), is one of those new releases – and a film with an unexpected North Carolina connection through its starring ship.

Clocking in at a taut 91-minutes and based on a novel written in 1955, “Greyhound” has all the hallmarks of a successful summer movie: an A-list actor, a proven director and thunderous action sequences rendered in faithful detail. The ship captained by Tom Hanks’ character in the film, the USS Keeling, is a work of fiction – however, one of the primary ships used in the on-location filming of “Greyhound” once had a very real run-in with the USS North Carolina that ended with a hole in its hull.

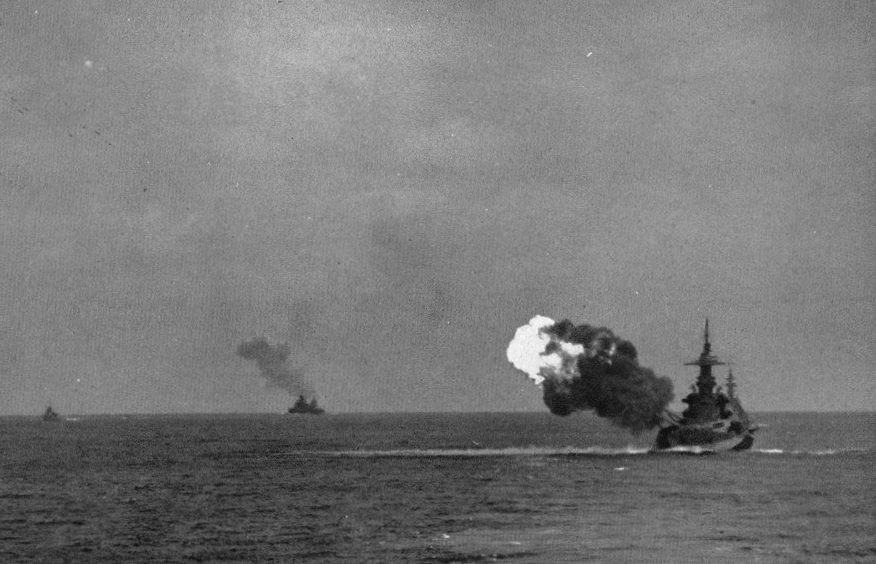

USS Kidd (DD-661) underway, 1951

The USS Kidd, a Fletcher-class destroyer that saw service is WWII, is a museum ship and National Historic Landmark berthed in Baton Rouge, Louisiana. The vessel is notable for being the only surviving WWII-era destroyer in its original wartime configuration, complete with “Measure 22” camouflage paint.

The ship’s era-appropriate fittings made it an ideal filming location for “Greyhound” and real-life counterpart for the USS Keeling. The destroyer, measuring 376 feet bow-to-stern, is dwarfed by the USS North Carolina, however – a fast battleship 729 feet long and displacing 36,00 tons worth of water. According to first-person accounts in both the USS Kidd and the USS North Carolina’s records, the two ships once encountered each other in a training exercise.

The first damage the USS Kidd ever received was done by the guns of the USS North Carolina, completely by accident. In a recollection from Rear Admiral Allan B. Roby, as the USS Kidd was cruising in the central Pacific with a task force en route to the Gilbert Islands, permission was given for battlegroups to conduct training exercises “as they saw fit.” One exercise in particular involved a destroyer division to charge a capital ship at high speed just before the end of the working day, “just before the daily call to darken general quarters.”

North Carolina underway on June 3, 1946.

In the “game,” the destroyers would charge the targeted ship, fire a spread of torpedoes, and then “zoom off, making smoke and zigzagging erratically to avoid destruction by the battleship’s guns,” according to Roby. How the crew of the battleship being attacked could “win” would be to spot the attackers and fire “star shells” – flares fired from deck guns, essentially gigantic fireworks – that would illuminate the attackers from behind, a tactic that would give gunners an easy target to obliterate in real-world conditions.

On one particular morning, the USS Kidd approached the USS North Carolina for a surprise attack as the skies were still relatively dark and its crew was just waking up for the day shift. Rear Admiral Roby’s account is as follows:

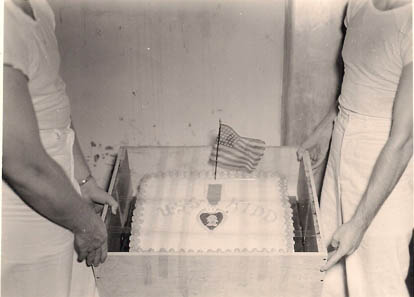

“Her lookouts were on their toes, however, and as we charged in, we could see the dull red flashes of their five-inch guns shooting at us. Fire control doctrine required them to track us in, aiming for hits, and then crank a star shell correction into the gun director to elevate the guns above the target so the star shells would burst 1,000 feet above and 1,000 yards behind, silhouetting us as a sitting duck. Alas! The fire controlman forgot to crank in the star shell correction. We heard two loud bangs, which were followed by much yelling from over our TBS: “Cease firing, you are hitting us.” I went down from the bridge to assess the damage and was greeted by the rich, fruity smell of good brandy. One shell had passed through Dr. Herendeen’s stateroom, smashing the ship’s medicinal brandy safe and turning his entire wardrobe of uniforms and civies into rags. The other shell came into a compartment just below and out the other side at the waterline. Every time we plunged into a swell, there was a column of water five inches in diameter blasting in from each hole. We got permission to stop while we assembled shores, wedges, and skillsaws for damage control, and before long we were back in formation. That afternoon, we were ordered alongside the North Carolina and a large, mysterious-looking package was sent across by highline. When we opened it, we found a huge cake, big enough to feed all 300 of us and decorated as a Purple Heart ribbon.”

Another account of the incident comes from inside the USS North Carolina’s 5-inch gun mount, from Seaman First Class Michael Horton:

“They made me first loader on a 5-inch…. (One time) we were firing illumination star shells, and I was asleep in the mount. Of course, we were in automatic and this was practice. There were only two of us in the mount. The rest of the crew was outside the mount. Well, out of this cold sleep, the mount captain grabs me in the shirt and starts screaming at me to load. He had the headphones on, you see, so he got the order to load. Since the rest of the crew was outside, he takes the powder can and throws it in. I jump up and grab the shell and load it and rammed it. I never heard as much confusion in my life. We had fired into the USS Kidd, one of our own ships. These two little hands are the ones that loaded it; but I was only a seaman, so it wasn’t my responsibility. This was the officer’s and director’s fault, I suppose. Anyway, there were no casualties on the Kidd, but she took a direct hit.”

One unexpected damage-control drill and an apology cake later, the USS North Carolina and the USS Kidd were both back in formation and continuing on to their destination. The two ships would encounter each other again, both in peace and wartime, but the friendly fire was thankfully a one-time occurrence.

Two men holding a cake inside a box. The cake is decorated USS KIDD with a purple heart. American flag flying. (photo via Battleship North Carolina)