“Straight Edge Finance” is a column written by Clark Troy, and presented by Red Reef Advisors

There is a lot of hullabaloo about interest rates these days. People got used to the ultra-low interest rates of the post-financial crisis, which blended so effortlessly into the even lower interest rates of the COVID and post-COVID era that people lost sight of how absurdly cheap money had been in the 2010s. Then we had inflation during and after COVID, for a variety of reasons. So central banks raised interest rates and reduced the size of their balance sheets, which had the effect of driving rates up further. But are rates really high?

Wall Street benchmarks the whole world on the yield on the 10-year Treasury bill, but Main Street lives and dies by the rate available on a 30-year fixed mortgage.

The chart above — courtesy of our friends at the St Louis branch of the Fed, a great font of a wide range of trustworthy economic data — shows average rates on 30-year fixed mortgages over the last half-century and change. As we can clearly see in the chart, the rates prevalent today aren’t that high at all. They are in fact just about as low as they ever were prior to the financial crisis of 2008-9. The fact that 30-year rates are as high as they are might reasonably be viewed as an indication that, for the first time since the crisis, rates are roughly back within range of their historical norms, that we’ve begun to put the crisis behind us, if we can forget for a moment about the sheer size of our aggregate Federal debt and a few other things.

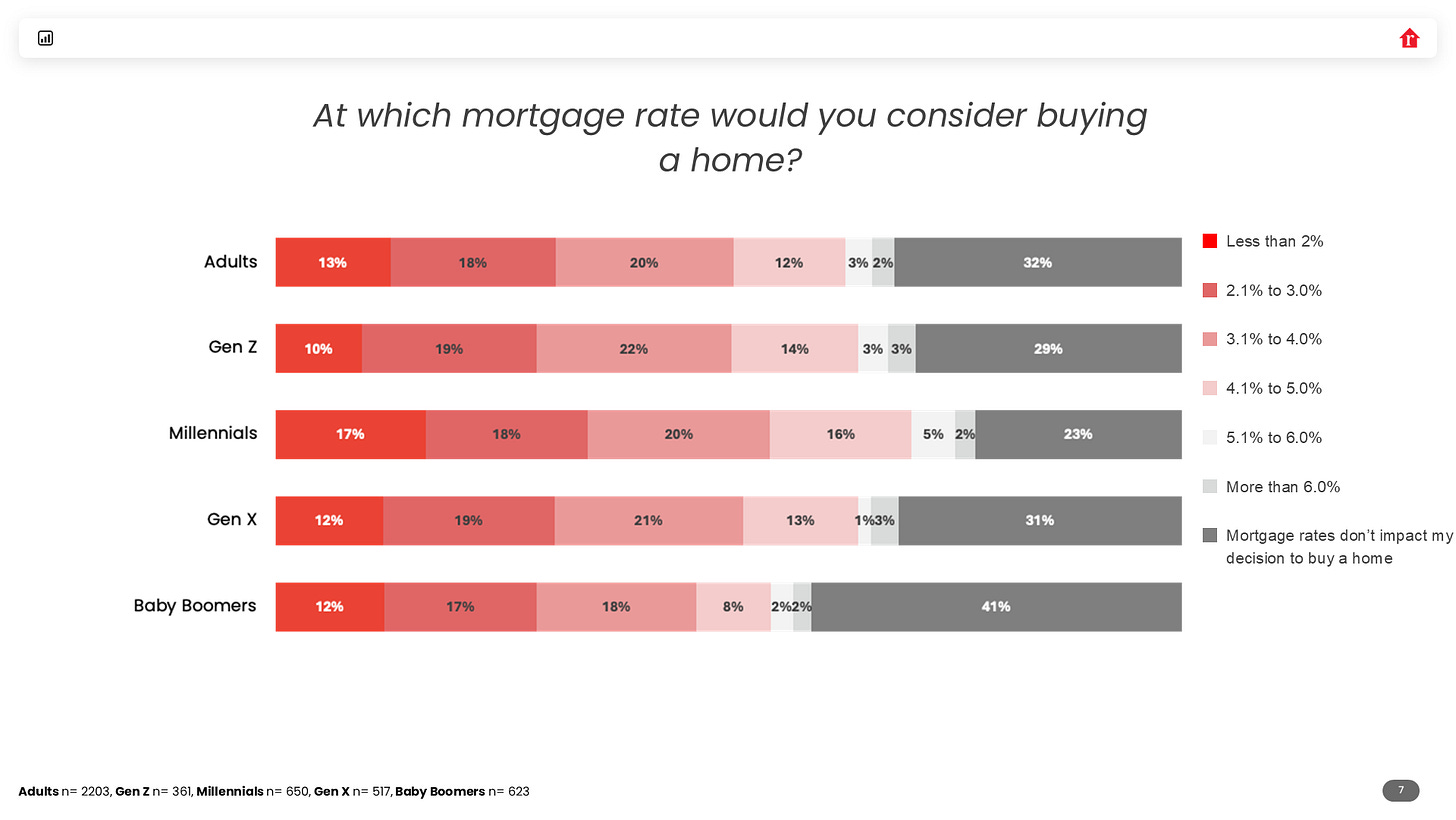

But Americans have become accustomed to the ultra-cheap money available to us over the last decade and a half. As rates fell, we all became financial geniuses and refinanced our mortgages. Lots of people have rates somewhere around 3% and are so enamored of their low payments that they don’t want to sell their homes, which would oblige them to finance a new one at a higher rate. Nor, for that matter, are people willing to buy at such “high rates.” A recent survey from Realtor.com shows that more than a third of adults have delayed purchasing a home due to high rates. Roughly half of all adults said they wouldn’t consider buying a home until rates were below 4%, and the percent of younger adults (Gen Z and Millennials) holding out for rates below 4% is even higher (see below chart from Realtor.com).

Let’s pause to summarize and think this through: more than half of American adults who might otherwise think about buying a house won’t do so till rates go down about 2.5% (250 basis points or bps).

Well what causes rates to decline by that much? Historically, it has been recessions and the Fed both lowering reference rates in its control and (over the last fifteen years) printing money by buying up bonds to force rates lower and help the economy emerge from crisis. But the catalyst to these actions is some sort of a crisis, typically accompanied by rising unemployment. In those kinds of situations, people don’t just bound out of their seats and rush off to buy a house. Far from it.

President Trump has been trying to exert his will over the Fed to twist its arm to lower rates of late, threatening to finder Fed Chair Jerome Powell and cooking up pretexts to force the resignation of another member of the Fed’s rate-setting board. Powell recently signaled that poor recent employment data appear sufficient to justify a reduction in rates at the next rate-setting meeting. But not by the 250 bps people say they need to buy a house. Certainly not, as inflation continues to run hotter than the Fed would like (the most recent inflation print was 2.7% — 35% above the Fed’s target 2% inflation).

Certainly we should all hope that the Fed maintains prudent process discipline around rate-setting and is able to do so on the basis of professionally-gathered economic data, like those provided by the BLS, which tracks unemployment. We have examples from recent history of what can happen when a head of state pressures its central bank to hold rates artificially low.

Back in 2022, Turkey was experiencing both slow growth and high inflation. President Recep Tayyip Erdogan, who had become increasingly autocratic since ascending to the top job in 2014, pressured the Turkish central bank to hold interest rates low. It didn’t end well. By June of 2023 a new head of Turkey’s central bank raised its key interest rate from 8.5% to 15%. Inflation at the time was at 40%. Two years later, inflation is down to 33.5% while interest rates have risen to 29.3%.

Now, America is not Turkey and the fact that the dollar is the world’s dominant reserve currency helps us sell our debt and keep interest rates down. It’s very hard to see US inflation ever vaguely resembling Turkey’s. But the basics of letting central bankers do their jobs and Presidents do theirs apply in both places.

The interest rates we want are not the lowest rates, but the right ones. Not too hot, not too cold, lest we be devoured by bears or trampled by bulls. Rates rise and fall over time, guided by bankers but ultimately set by markets. They were very low for a long time. We should all hope that we never again see rates as low as those prevalent since the financial crisis, because if such rates return, something will be very, very wrong.

Clark Troy was born in Durham and educated in the Chapel Hill-Carrboro City Schools, then elsewhere. He is a financial planner at Red Reef Advisors and may be reached at clark.troy@redreefadvisors.com. When not working, he reads, plays sports, blogs, naps, drinks coffee, studies languages and plays guitar, not necessarily in that order.

Clark Troy was born in Durham and educated in the Chapel Hill-Carrboro City Schools, then elsewhere. He is a financial planner at Red Reef Advisors and may be reached at clark.troy@redreefadvisors.com. When not working, he reads, plays sports, blogs, naps, drinks coffee, studies languages and plays guitar, not necessarily in that order.

For more from Clark, subscribe to his substack directly and check out other “Straight Edge Finance” columns in the full archive on Chapelboro