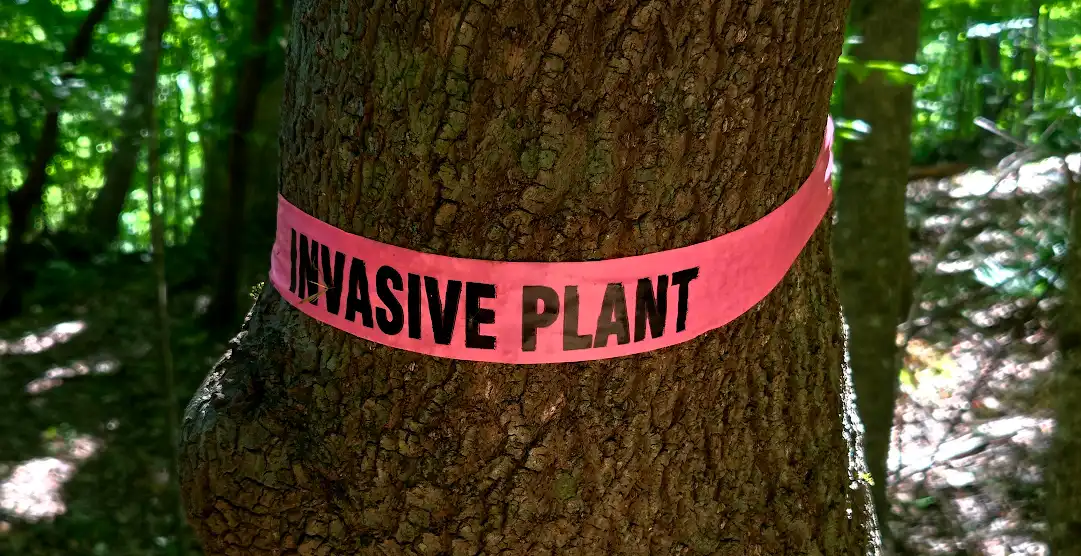

Nearly every time I’m afforded the opportunity to speak to a group of folks, give a tour or break out into a spontaneous rant, I find the topic of invasive plants comes up. It’s a comfortable subject, perhaps, a familiar piece of furniture in the living room of my brain that I’ll cheerfully flop over onto after the syllable count goes over some certain number. (I wish I knew what that number was. Anyway…) Thirty years into this plant-thing and I’ve allowed the subject a fair bit of room: books on the shelves, short stacks of paper, collated and stapled and shot from a dozen different printers, the job that I trade 29.7% of my life/time for in exchange for subsistence and some substance and – almost goes without saying –my head. And now, it appears, this column, the first in a meandering series around invasive plants.

What is a native plant, anyway?

What makes a plant native? First principles, right? I was raised up on axiomatic thinking. Define first, then deduce. Reason begets all beauty. Or something like that. Let me start off by noting that I’m not a fan of militaristic language in horticulture. I’ve tried for a long while to avoid throwaway expressions like “I’m going to tackle some weeds today.” or “We’re losing the battle against that damn stiltgrass!” Too angry. I get the sentiment; I agree that there are legit struggles we face as stewards of our respective plots. A good deal of what I do every day involves destruction. The great gardeners have killed way more plants than the merely good ones. Not sure where I sit on the spectrum, but I definitely have snuffed out my share of autotrophs. Sigh.

There is a lovely little primer on invasive plants here. It’s courtesy of the Cornell Botanic Gardens. It summarizes nicely what many who garden understand and work to correct. So bear with me as I dissect these few paragraphs just a bit to see if there’s anything of value for the purposes of this little article. (I’ll try not to get us lost along the way.)

The first sentence I’ll quote here:

“An invasive plant is one that is capable of moving aggressively into a habitat and monopolizing resources such as light, nutrients, water and space to the detriment of other species.”

Fairly concise, easy enough to understand from a vocabulary point of view. Syntax not challenging. Great…but I would add the following by way of clarification: we should only refer to nonnative plants as invasive. Native plants can be aggressive, bullies, bad actors, thugs, villains, pick your epithet, but should never be referred to as invasive. That distinction provides a fairly defined line of demarcation between those plants we welcome and those we challenge.

That’s a fuzzy line, however. As are most lines in the biological sciences. The second and third sentences in our chosen reference site illustrate this nicely.

“A plant is native if it has evolved and is adapted to local environmental conditions and is part of a natural community. A plant is nonnative if it has been introduced into a new location by human activity, either intentionally or by accident. It may or may not be invasive in a particular location.”

What is local?

It’s a matter of scale and how we choose to recognize the term “local”. Local to where? Orange County, the Piedmont, North Carolina, the Southeastern United States, the United States, North America? You get my point. It’s what makes common names of plants so interesting, the provenance of a thing and the vernacular that surrounds that thing. But that’s a topic for another time. The point here is that we can talk about a plant being native to a place based on shared assumptions of how big/little that place is. Once we have agreed upon scale, we can then agree on its role in the system it inhabits. Its invasive potential. That’s particularly interesting to me. It’s an essential part of my job, in fact, evaluating botanical behaviors over time and judging the guests at the garden party.

Who brought them?

There are many unruly party guests in your average garden. The ne’er-do-wells that I’m discussing here are all cheerfully listed on the North Carolina Invasive Plant Council’s website. NC-IPC is an excellent resource for all of us who wish to include invasive species detection and removal as part of our regular gardening chores. And honestly, who wouldn’t want to at least consider spending a bit of that precious outside time considering the wanderers, interlopers, waifs, strays and drop-ins that surround us in field, forest, landscape and garden? Fascinating, really, when one allows the time to consider just how good we are as a group, as a species, at moving things around the place. Our ability to redecorate our planet is extraordinary. I’m focusing here on our well-developed ability to act as a dispersal vector for all manner of less mobile critters.

Unintended consequences

Y’all know stiltgrass (Microstegium vimineum). Certainly within everyone’s top 10, maybe top of the heap of the reviled and the misbegotten. It’s a real stinker, alright. Showed up as discarded packing material for porcelain shipments, this plant has spread into 26 states since first being noticed in 1919. Remarkable for a few hands full of biodegradable junk–of course you would just toss it into the road. (I don’t think twice about chucking the woody bits of stem that I’m not going to use in that night’s recipe. Often they go straight into the garden. Easy, environmentally friendly, feels good.)

Stiltgrass (Microstegium vimineum), the scourge of every gardener

The stiltgrass story went a bit like this: there’s this group of humans on the other side of the planet over a century past that were charged with putting fragile items of worth and beauty into boxes so that they may be loaded onto ships and floated across an ocean to end up in the hands of those with capital and desire. And in order for that transaction to progress in the way the economy wished, that shipment needed to arrive in the selfsame condition coming out of the box as it was going in. So we invented packing material. We opted for the renewable stuff, this grass that’s growing everywhere, fast. It’s springy, lightweight and free. Awesome. Problem solved and no additional cost to seller or buyer. Capital flows and some folks quite ignorantly transport a plant from there to here. Well…in the case of this supergrass, a few of those discarded off-cast stems, deprived of all connection to soil, light and water for weeks in the hold of a cargo ship, managed to survive. Likely, there were some fruiting stalks with viable seed within the slender sheaves. And, as here had a similar climate to there, that seed manages to make its way to soil and here we are just a little over 100 years later and we’ve got stiltgrass frickin’ everywhere. Despite being an annual, it’s a monster.

Moreover, an entire economy has been cobbled together around the expressed desire to eliminate this exotic invasive (the preferred terminology, if a bit clunky) and others that have found their way into our little garden party. The better-living-through-chemistry-clique has been hanging about in the kitchen with their briefcases full of vials and ampoules and test strips and flasks, cooking up all manner of poisons for these undesirables. Lovely! Right?

Remember what I parenthetically noted a page back about not getting us lost? I just checked the map and well…let’s get back to the party, I think they’re actually playing some music from a decade I remember.

Our little excursion highlights a way in which an exotic plant can land on a distant plot. This movement around the globe has increased dramatically in the last five centuries. We are so good at this, incorporating mobility into our life histories, allowing us to be a fully naturalized species on nearly every scalable piece of inhabitable land. Cosmopolitan is the term botanists use for those plants that share that characteristic. The dandelion is a great example, and I’ll be sharing some thoughts about that little gem in a column a bit later on.

The cosmopolitan dandelion (Taraxacum officinale)

The best intentions…

For now, let us consider that nearly two-thirds of the unwelcome guests at our continent-wide gathering have arrived directly as a result of our own desire to garden. Horticulture, the pursuit of a lovelier landscape. The perhaps hard-wired desire to change what we first encounter into something closer to what we left behind. Hard-wired as perhaps that desire comes from a place of self-preservation. When humans jumped across an ocean, we brought with us those items we felt necessary for survival in an unknown place. That included plants from our previous homes. As we started squatting on the lands we encountered and changing the local landscape, we proceeded to change the local ecology. We added plants to an already functional system. Some of those plants have continued to live here without much impact, like the couple down the street that you are always going to invite because they’re nice, they engage in worthwhile conversation, and they usually bring a plate of deviled eggs. Yum.

There are a bunch of exotic plants that we consider harmless as they have not spread themselves too aggressively, nor have they caused harm at local scales. Some have naturalized, finding their little corner at the party to settle into and enjoy their time. Engaging with other company, well-behaved, reasonable, polite.

Snow camellia (Camellia japonica), Margot’s Mom’s favorite

Who doesn’t like a camellia in full bloom as the cool echoes of winter are retreating into all the unused coat sleeves?

And the dizzying dance of bumblebees around the glossy abelia (Abelia x grandiflora) that sat on the other side of the optimistically opened August window.

Glossy abelia (Abelia x grandiflora), loved by pollinators and people alike

Azalea flowers in colors that almost hurt to look at for too long a spell….

Azalea, the perennial Southern staple

Those exotics that get out of hand, however, those are the ones we call invasives. That list I mentioned earlier? Those are the ones. Some of them, anyway. Note that list is specific to North Carolina. Many states have their own. There is overlap, to be sure. As I build on this topic, we’ll be looking at some of the plants from this list. There are many that I am familiar with (I’ve already broken the bad news about Lenten roses (Helleborus orientalis), some less so. As I continue to work the room, I’m certain I will bump into those I have not had a chance to meet yet.

I’ll throw out this name on my way out the door– Asian bittersweet (Celastrus orbiculatus). Nonnative vine, you’ll likely see it coming up, through and over your more beloved shrubs. This is a bully of a plant. I’ve encountered examples in the western part of NC with 6-inch diameter stems, climbing 60 feet or more into local trees. This vine will grow and grow and grow and overtake its scaffolding, shading out the limbs and leaves that provided for support, tearing down the tree in time. The flowers/fruits are quite attractive; however, this vine has been harvested and crafted into decorative wreaths for generations. Unfortunately for the native bittersweet (Celastrus scandens), the nonnative vine has showier fruits. So it won the popularity/utility contest.

Asian bittersweet (Celastrus orbiculatus), on its way to swallowing a wall

When the cultivated bittersweet vines were left on their own, when the few stems that were not attractive enough for harvest were not cut and dried, those seeds begat the multitudes that have come forth to swallow our viburnums and abelias and gardenias and boxwoods and…

The gardenia prized for its sweet scent

My point: having a plant in your garden that you know to be invasive and allowing yourself the excuse that you’ll “manage it” as justification for its continued presence ignores the fact that the plant will outlive you and that the next steward of the plot may not share your enthusiasm for gardening. In short, think long. I’ll get off that soapbox now, vertiginous and wobbly.

So many soapboxes…and the colors, oh my!

All photos by Geoffrey Neal.

Geoffrey Neal is the director of the Cullowhee Native Plant Conference. You can see more of his photography at @soapyair and @gffry. Margot Lester is a certified interpretive naturalist and a writer and editor at The Word Factory.

About the name: A refugium (ri-fyü-jē-em) is a safe space, a place to shelter, and – more formally – an area in which a population of organisms can survive through a period of unfavorable conditions or crisis. We intend this column to inspire you to seek inspiration and refuge in nature, particularly at the Arboretum!