“And then my heart with pleasure fills.

And dances with the daffodils”

From “I Wandered Lonely as a Cloud” (sometimes called “Daffodils”), a poem by William Wordsworth

Deep breath. Sunday morning. Looking out from my house onto the garden. Daffodils coming up all over. That’s what it’s all about right now. The full-throated shouts of winter echoing about, the fresh soreness of a long hike under a warm sun (70 degrees on the 1st of March!), jays and sapsuckers clocked in and busily working the back woods, the worth of a weekend measured out in worthwhile chores, smiles and music and careful food. But above all that, on the first day of the last chunk of winter, the first preface to the coming chapters of spring, longer days and warmer nights, we are fortunate to share ground with the daffodils.

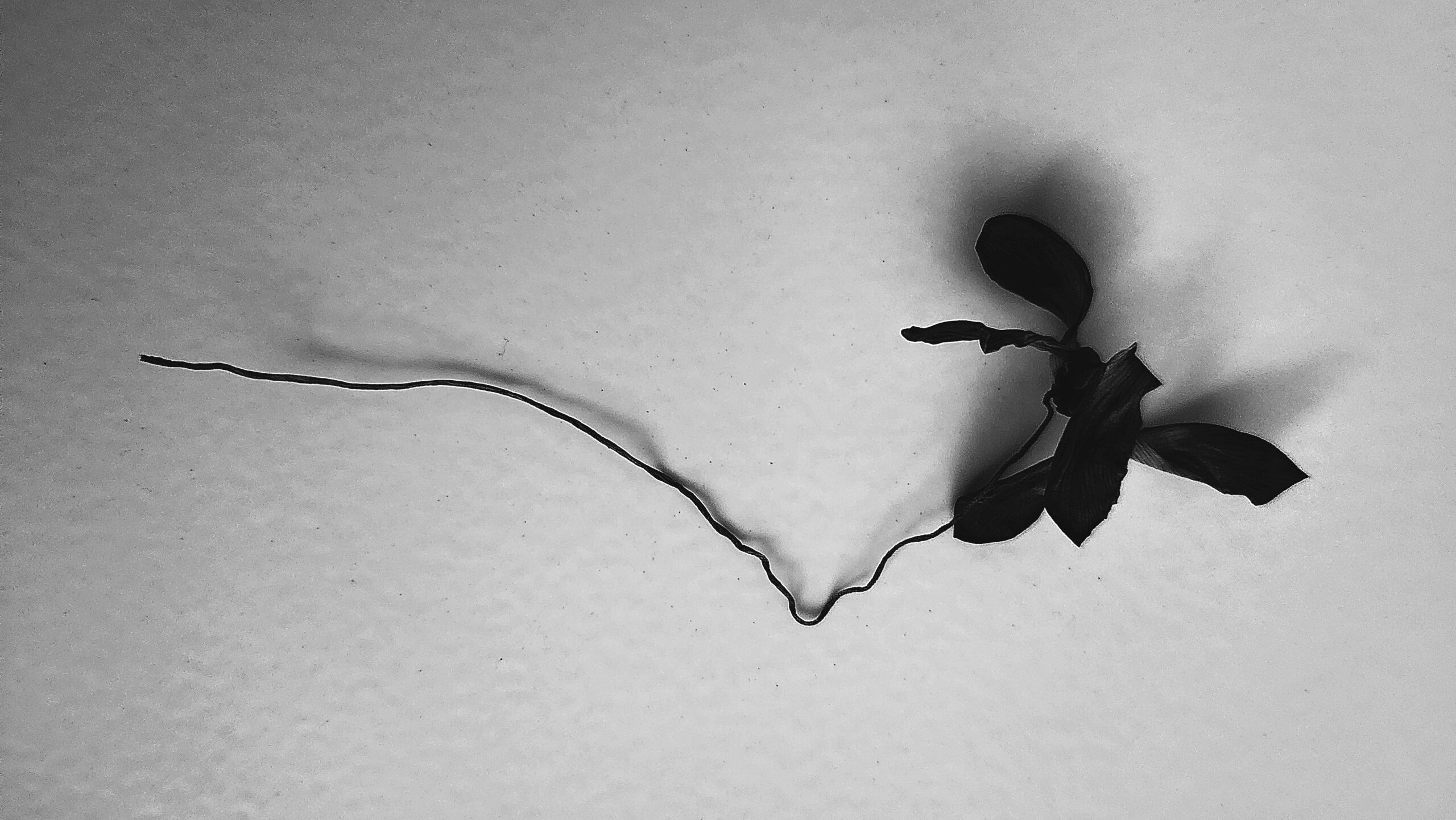

In lieu of the perfectly still pool wherein the reflected markings of time are sometimes contemplated (decried, admired, pick your mood), I prefer the clean green lines of leaves and the oftimes fragrant blooms. Certainly my favorite plant this time of year, and one to notice as you find yourself moving through town. I leave off with fewer words this month, loads of photos.

(all images courtesy of Geoffrey Neal, except “Redbud,” which was taken by Margot Lester.)

Narcissus: The word goes back a thousand years. Longer still in the original Greek. Longer still to some “pre-Greek substratal origin” (thanks, Merriam-Webster). The myth around the charming lad in mad love with his reflection makes for nice cautionary. So many of the Greek myths were really lovely little life lessons, after all. Here’s how this personality type ends up – how about let’s not do that (said without really saying)? Fascinating, right? And this is about gardening? Am I in the right room?

The genus Narcissus comes to us from Europe, is a perennial bulb, and has long been planted and played with by gardeners of all stripes over centuries. While not native to the Southeastern United States, the cheerful jonquil has become as much a part of the vernacular of the Southern garden as the Camellia, the Abelia, the Forsythia and the Crepe Myrtle – and they take up a lot less space.

(You may be wondering if there’s a rule about capitalizing common names. The rule is “there is no rule”, though we more often than not see them capitalized in the literature. I prefer this sometimes for its old-fashionedness…other times I feel quite contrarian about it and want all common names rendered – common.)

The daffodil has few enemies in our gardens. None of our munching marauding mammals care for this plant. That includes deer, rabbits, squirrels, moles, etc… A reinforcing reward for horticulturists over the years.

The plants are also long-lived. Perhaps you’ve noticed the pop of color on the side of the back road out in the county? The site of a long-gone house, maybe a stone edge or chimney relic to mark its prominence. The daffodils remain. With the dooryard pecan, perhaps, or a line of redcedars along a lost fence line edge. There are old daffodils on the verge as you come up Merritt Mill Road from the bottom. I’ve seen more than a few on my commute into Chatham County from campus.

As the older bulbs subside, pulled deeper into their earthen beds each year by shortening roots, new offset offspring arise to take their place. Digging older patches of bulbs will reveal this crowded structure and the bulbs will thank you for the occasional thinning and lifting. This is a worthwhile bit of occasional maintenance, even as infrequently once a decade. When you lift your bulbs to replant, feel free to set a few aside to share with your people. Or bring some to me or Margot, that’s always fine.

Dear readers, I encourage all y’all to get yourselves to a place where you can acquire some daffodil bulbs and get them into some soil. You do not need a full-blown garden; a few bulbs in a pot will do nicely. If you’re growing a bit of rosemary on your porch, parsley on your patio, add a few bulbs under those plants and enjoy the bit of color when it comes. If you have the time and the space, get ahold of a couple hundred and spread them about. This small amount of digging will reward you and your successors.

Pssst. Over here.

When Geoffrey and I are out botanizing and naturalizing, I’m usually hanging around in the background, kind of like I do with this column. Sometimes, though, I interject interpretive insights (he might call them “interruptions”, but whatever).

The daffodils are for sure telling us spring is coming, but I’ll know it’s actually arrived when the redbuds (Cercis canadensis) begin busting out all over.

They’re not very showy right now, but just you wait. Before too long, clusters of pink and magenta flowers will erupt all along the branches, brightening up the canopy with bursts of much-needed color. And they’re not just eye candy – their nectar and pollen are a good early-season food source for bees and butterflies. And we humans can eat the flowers, too – as long as chemicals haven’t been used nearby. Some old-timers I knew coming up even used them to make jelly. If you want to give that a try, check out Whitney Johnson’s recipe.

The flowers don’t deserve all the attention, though. The leaves that emerge after the bloom look – depending on your orientation – like green hearts or spades. That’s cute, but what comes next is really cool: seedpods! These little packages are what give the tree its Latin name. “Cercis” derives from kerkis, the Greek word for a weaver’s shuttle, which the pods do kinda resemble if you hold them sideways. On the trees, however, they look like leathery bean pods, which is why my brother and I called this species “bean trees” when we were little. In addition to the ones that grew wild in the woods, local nurseryman Bert Kednocker gifted an ornamental redbud to my parents on the occasion of my brother’s birth, because – wait for it – little bro is a redhead. Gotta love botanical humor.

If you want to observe these rosy beauties more closely, join me as part of the Redbud Phenology Project. It’s essentially a data-driven nature journaling activity to study how plants change over time. When you sign up, you use an app to report notes every few days on what you notice about a redbud. (I use the redbud right outside my backdoor.) There’s a handy key that outlines exactly what to look for so data collection is easy and just takes a few minutes. It’s a fun way to deepen your connection to nature and be a part of a huge community science network that helps the pros understand more about redbuds, climate change and the status of spring. This is a great time to sign up and familiarize yourself with the program before the action starts. Come along!

Alright. That’s enough from me. Back to Geoffrey for the last word.

(Cercis canadensis) in bloom.

Coda

OK, a few more words…pleasepleaseplease take some time on one of these delightful late winter days when it’s not actually cold to take a walk, look at some plants, smile at folks, maybe say hello. That’s all. Back in April.

Geoffrey Neal is the director of the Cullowhee Native Plant Conference. You can see more of his photography at @soapyair and @gffry. Margot Lester is a certified interpretive naturalist and a writer and editor at The Word Factory.

About the name: A refugium (ri-fyü-jē-em) is a safe space, a place to shelter, and – more formally – an area in which a population of organisms can survive through a period of unfavorable conditions or crisis. We intend this column to inspire you to seek inspiration and refuge in nature, particularly at the Arboretum!