Often attributed to Mark Twain — perhaps mistakenly, since no historical source shows he actually made the statement — “History doesn’t repeat itself, but it often rhymes” is a common and apt refrain when discussing the connection between historical perspectives and current events. By drawing on knowledge of what happened in the past, and why, we are better able to understand the flow and direction of the history collectively created in each new day.

“Past Rhymes With Present Times” is a series by Lloyd S. Kramer exploring historical context and frameworks, and how the foundations of the past affect the building of the future.

People in Fear, Fugitives in Boston and Immigrants in North Carolina

The American defense of human rights faces nationwide dangers as the Trump administration arrests thousands of immigrant workers.

While most Americans are preparing for the winter holidays and happy family reunions, millions of our immigrant neighbors are fearing authoritarian knocks on their doors or hiding from possible detainments and deportations.

Federal agents from the Customs and Border Patrol (CBP) and the Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) have arrested hundreds of people in North Carolina and moved them to out-of-state detention centers, where they remain isolated from their families and friends.

This life-shattering assault on immigrant communities dehumanizes the detainees with all-encompassing charges of criminality and replicates the injustices of past attacks on Native Americans and African Americans. Most Republican leaders are nevertheless celebrating these cruel arrests as actions that protect rather than destroy essential national values.

“I’m very proud of what these men and women are doing,” Congressman Tim Moore said in a recent interview, “to keep our border secure and remove dangerous folks from our community and other communities around the country.” Moore represents North Carolina’s 14th Congressional District near Charlotte, yet he is apparently oblivious to the human and social costs of repressive actions in the real-world communities that surround him.

The Economic and Human Costs of “Immigrant Removals” in Our Communities

The financial costs of massive CBP/ICE operations divert much-needed funds from other community needs, but the arrests of immigrant workers also weaken businesses in every city where federal agents launch their raids. Restaurants, shops, and workplaces lose thousands of dollars every day as customers and workers stay away from all targeted neighborhoods.

The most profound losses from these raids, however, take place in the personal lives of people who are swept away from their jobs and families as they disappear into faraway prisons.

Immigrants resemble all other human beings in their range of good and bad behaviors as well as their virtues, flaws, and personal problems, but careful, journalistic investigations confirm that very few of those arrested in the current CBP/ICE raids have ever been guilty of truly criminal actions. They are simply struggling to survive within a broken immigration system that blocks their legal and documentary progress toward worker and residency rights in American society.

We can see the human meaning of CBP/ICE attacks on specific persons in North Carolina as we learn more about recent CBP raids that seized 23-year-old Fatima Iseela Velasquez-Antonio and 27-year-old Moises Benitez Diaz at construction sites in Cary. Neither of these hardworking people were allowed to post bond or find other legal protections before they were immediately dispatched to detention centers in Georgia.

Velasquez-Antonio escaped from Honduras at age 14 after her mother died of cancer and her father was murdered. She lived with family members in North Carolina, but she never gained legal asylum as she made her way through high school, launched her work career with an HVAC company, and purchased a home with her partner in Wendell.

The recent CBP raids also captured Benitez Diaz, who came to the United States from Mexico when he was in the first grade. Developing his impressive skills through early work in the construction industry, Benitez Diaz established his own roofing company and married a woman who was expecting their third child when he was taken to a Georgia prison.

A final story shows how innocent people are being brusquely expelled from American communities. In the week before Thanksgiving a 19-year-old college student named Any Lucía López Belloza was leaving Boston to visit her family in Texas when ICE agents arrested her at the airport and deported her to Honduras.

Like countless other young immigrants, Belloza came to the United States as a child, excelled in school, and went on to college, but she was deported during the Thanksgiving holidays because of an unknown deportation order that was issued when she was nine years old.

Her family is now trying to bring Belloza back to her college in Boston, where the history of struggles for the rights of “fugitive slaves” in the 1850s connects with the struggles of fearful people who are hiding from CBP/ICE agents in 2025.

The Fugitive Slave Act and Fearful People in the 1850s

The United States Congress enacted the Fugitive Slave Bill of 1850 in response to Senate slaveholders’ demands for more northern arrests and deportations of formerly enslaved African Americans.

Although an earlier Fugitive Slave Act had existed since 1793, enslavers were enraged that numerous northern cities later created “personal liberty laws” to block the re-enslavement of African Americans in their jurisdictions. Southern political leaders viewed these places as what might now be called sanctuary cities for “criminals” who had illegally migrated beyond the reach of the slaveholders’ efforts to reclaim their human property.

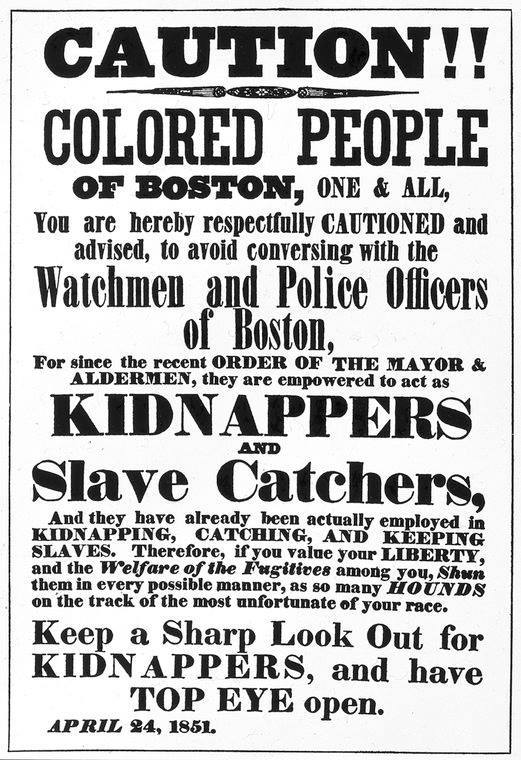

A poster dated April 24, 1851 warning colored people in Boston to beware of authorities who acted as slave catchers. (image source)

Boston became one of the best-known urban sanctuaries, in part because more than 600 once-enslaved people were living there by 1850 and in part because local juries would no longer convict those who supported illegal flights from enslavement.

Senator James Mason of Virginia therefore secured passage of a new Fugitive Slave Law that would give slaveholders “a remedy” for the illegal escape of runaway slaves and expand the punishment for such criminal behavior “in every possible respect till it becomes effectual.”

The new law thus eliminated the right of habeas corpus for “fugitive” slaves, barred jury trials and bond-supported releases for arrested suspects, and empowered specially appointed commissioners to ensure that guilty persons were quickly returned to their southern enslavers.

Government officials in Boston and other cities were required to arrest formerly enslaved persons for their criminal migrations. The unreliable local enforcement of the new law was widely augmented by federal marshals who searched for undocumented Black people wherever they might be working, raising families, or ignoring the legislation that mandated their return to the slave states in which they had been born.

This aggressive search for “fugitive slaves” generated deep fears among all Black residents in northern cities. The abolitionist John Brown reported in a letter from Springfield, Massachusetts that his Black friends “cannot sleep” because of constant worries about “either them or their wives and children;” and Brown wanted his own family “to imagine themselves in the same dreadful condition.”

Resisting the Fugitive Slave Law

Most northern state governments reluctantly cooperated with the new search for “illegal” people, but African Americans and their white abolitionist allies met in Boston and other cities to condemn both the Fugitive Slave Law and the expanding arrests as grievous violations of the Declaration of Independence and the “Golden Rule of Christianity.”

Ralph Waldo Emerson wrote that nobody could obey this law “without loss of self-respect.” The future Senator Charles Sumner also argued that the “irresistible” tide of outraged public opinion must transform the terrible legislation into “a dead letter,” while an energetic “Boston Vigilance Committee” began posting handbills to warn Black residents whenever “slavecatchers” came into the city.

Federal marshals nevertheless proceeded with their arrests, which included the detention of an “illegal” formerly enslaved man named Shadrach Minkins. An enraged crowd liberated Minkins from the Boston courthouse and helped him escape to Canada. Thousands of other Black residents in Boston, New York, and Philadelphia found their own assertive ways to elude the marshals or travel out of the country.

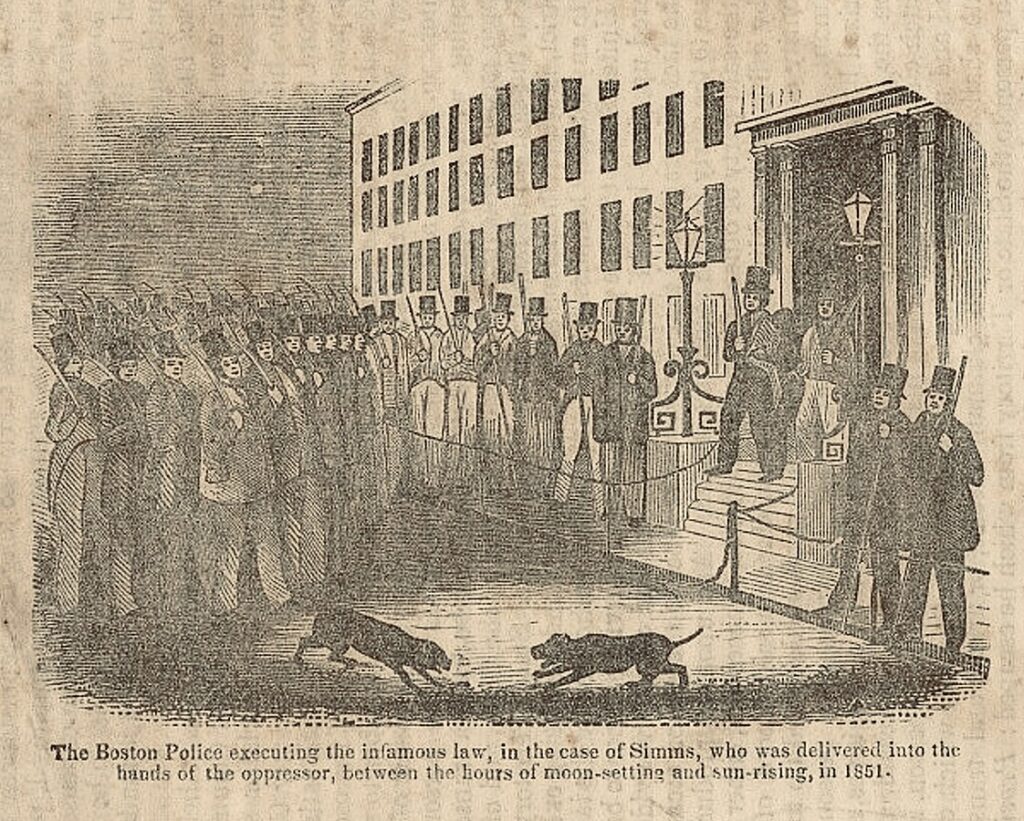

Despite the mobilization of angry activists, the continuing arrests soon carried “fugitives” such as Thomas Sims and Anthony Burns from Boston to re-enslavements in Georgia and Virginia.

Christian pastors often became the most vocal critics of the assault on “illegal” African Americans in sermons that denounced the deportations as a “monstrous iniquity” and the “vilest monument of infamy.”

Yet the Fugitive Slave legislation attracted unbending support from southern senators who foreshadowed current defenses of ICE arrests by claiming that federal marshals were simply arresting and deporting the Black criminals who lived illegally in northern cities.

The Boston Police executing the infamous law, in the case of Simms, who was delivered into the hants of the oppressor, befween the hours of moon-setting and sun-rising, in 1851. (image source)

The Fugitive Slave Law and ICE agents in 2025

The history of marshals and Black fugitives during the 1850s provides helpful perspectives for analyzing the current plight of immigrants because the law-and-order arguments of nineteenth-century southern senators can still be heard in the anti-immigrant ideologies of our own time.

In the words of State Representative Pat Harrigan (R-Hickory), “Sanctuary cities are not protecting immigrants. They are protecting criminals. That is a key distinction that we’ve got to understand.”

The Bostonians who offered sanctuary for “illegal” Black fugitives were also condemned for ignoring the distinctions that Representative Harrigan describes, which suggests why denunciations of the Fugitive Slave Act might still resonate among today’s anti-ICE activists and the families of imprisoned immigrants.

It is therefore encouraging to see how church leaders are again condemning arrests and detentions that portray freedom-seeking people as criminals. The Roman Catholic Bishops of the United States, for example, have summarized clear moral reasons to “oppose the indiscriminate mass deportation of people” and to “raise our voices in defense of God-given human dignity.”

The prospects for political freedom and human rights seemed dire in 1850, and those who opposed the cruel arrests of Black Americans surely wondered if their anti-slavery struggle could ever finally prevail. After fifteen years of intense conflict, however, the Civil War-era Congress repealed the Fugitive Slave Law, and the states ratified a Constitutional amendment to abolish slavery.

The struggle for human rights always faces setbacks and new obstacles, but the abusive agents of repression ultimately disappear, and new ideals or policies revitalize the long progressive journey of people striving to be free.

Photo via Lindsay Metivier

Lloyd Kramer is a professor emeritus of History at UNC, Chapel Hill, who believes the humanities provide essential knowledge for both personal and public lives. His most recent book is titled “Traveling to Unknown Places: Nineteenth-Century Journeys Toward French and American Selfhood,” but his historical interest in cross-cultural exchanges also shaped earlier books such as “Nationalism In Europe and America: Politics, Cultures, and Identities Since 1775” and “Lafayette in Two Worlds: Public Cultures and Personal Identities in an Age of Revolutions.”