Via the Orange County Arts Commission, Article by Brian Howe

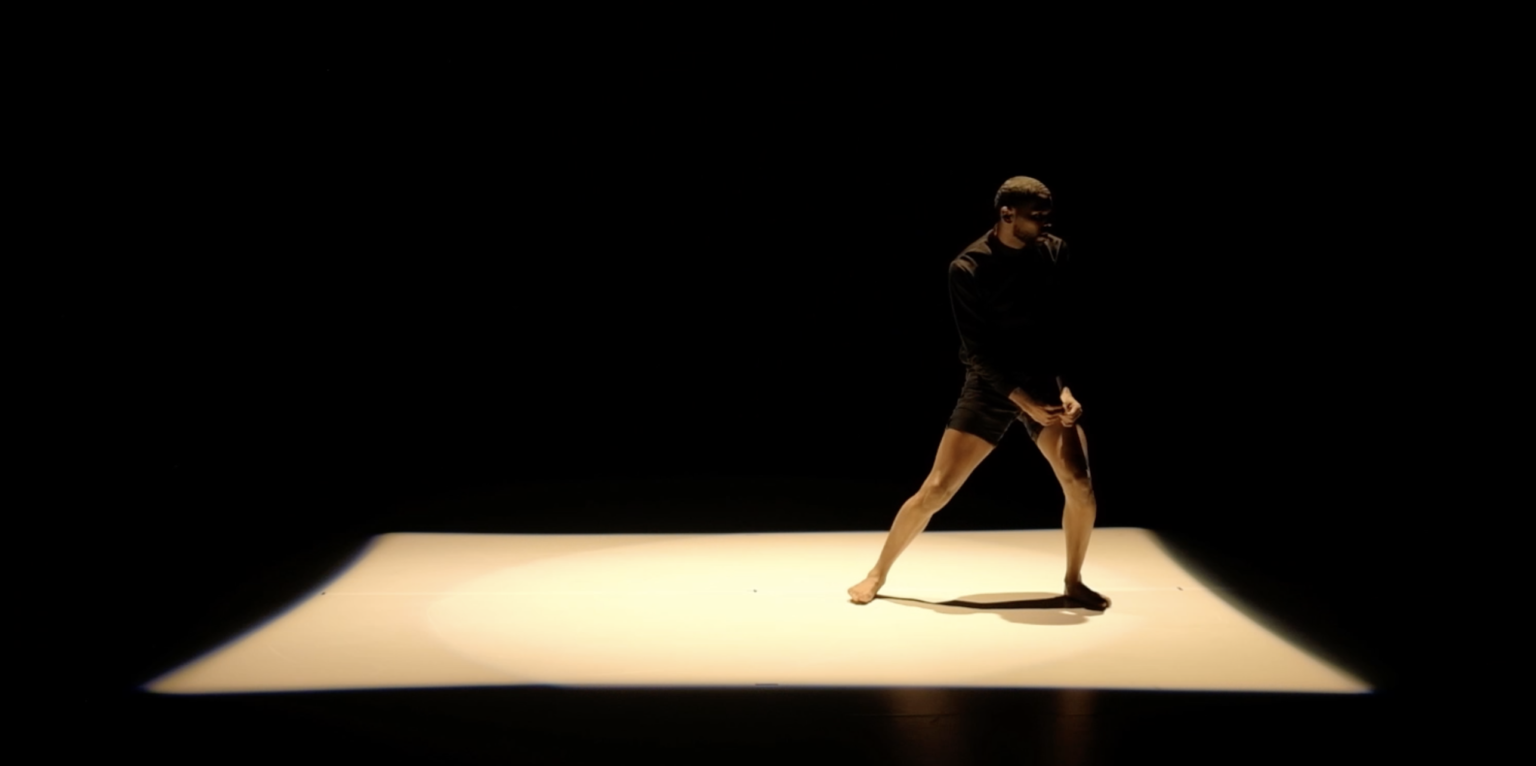

Anthony “Ay-Jaye” Nelson in Pain, Trauma, Triumph in the first show of The 20/21 Digital Commons. Photo by Wo Imaging.

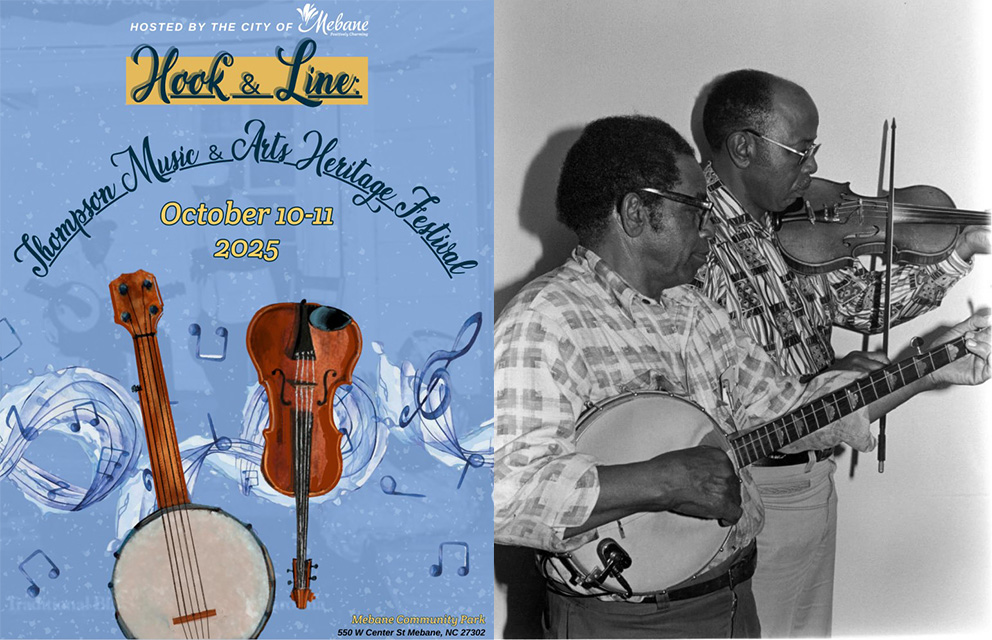

The Commons, the four-weekend local performing-arts festival that just got underway at UNC’s Carolina Performing Arts, is unique in many ways. One is just a social-distance necessity: the residencies awarded to four local artists are resulting in videos instead of live performances at CURRENT ArtSpace + Studio. But even this compromise prompted artistic discoveries, while other exceptional aspects of this young festival exemplify how presenters can turn community, inclusivity, and diversity into more than marketable words.

Instead of courting critical documentation, The Commons bakes it in—two local writers were hired to explore the process as well as the outcome. And instead of centering the usual theater and dance, it centers the spoken word, which takes its rightful place among the live arts, rather than being cordoned off in a poetry or storytelling festival.

Likewise, The Commons centers Black artists while forgoing the vaguely self-congratulatory “Black festival” framing that presenters sometimes use, which can seem more like a concession to glaring whiteness than a remedy. And, just as unselfconsciously, it drew in artists who were new to the arcane ways of project proposals, resulting in their first opportunity to fund a production on a university’s dime and studio time.

All of this developed naturally, through open submissions, from the strength of the proposals, a circle of relationships, and the exigencies of these times. The result, above all, is a treat for cooped-up arts lovers and a boost for four dazzling artists: contemporary dancer Anthony “Ay-Jaye” Nelson, slam poet Ayanna Albertson, hip-hop artist Eshod “Eternal the M.C.” Howard, and storyteller Johnny Lee Chapman III. But for arts presenters who want to dismantle structural white supremacy in reality, not just in appearance, it also illustrates a valuable lesson: it’s where you begin that determines where you’ll end up.

In a limited way, I can speak firsthand to this organic development. Debuting as a residency and festival for local artists in 2019, The Commons was created by Alexandra Ripp, the Mellon DisTIL postdoctoral fellow at CPA, whose role is now occupied by Lauren DiGiulio. Alex is a friend, and, over many Carrburritos, we came up with a plan to embed writers to produce a new kind of invested, non-objective criticism for a time when old lines of authority were justly crumbling. I published it in a special section of INDY Week, with very interesting results. But after Alex moved on from her fellowship, the coronavirus moved in, and I moved on from the INDY, it seemed destined to be a one-time experiment.

Then came Christopher Massenburg, whom you know as the spoken word and hip-hop artist and educator Dasan Ahanu. He’s also the Rothwell Mellon Program Director for Creative Futures, CPA’s newest grant-funded residency program, and it was he who led The Commons’ revival. Asked to help match writers with performers and arrange for INDY publication again, I happily did. But other things about the project are different, and it’s a joy to see it taking on a life of its own.

Dasan describes four main goals: to provide resources to local artists, to connect them with other creators, to deepen CPA’s connection to the local arts community, and to make sure Black and brown artists, emerging artists, and artists beyond theater and dance felt invited.

“Presenters and venues are always talking about community, but they’re not always accessible for local artists,” Dasan says. “Vocalists, poets, and a hip-hop artist probably normally wouldn’t think this is something they should be involved in. The idea was to do this in a way that artists who might not usually see themselves working with CPA, might see that.”

This was as simple as promoting the call for submissions through Dasan’s networks—“not just sending the information, but telling them, we want you to apply,” he says—rather than letting it echo in the usual white spheres where many such calls get stuck. A community panel featuring the likes of Kevin “Kaze” Thomas, Quentin Talley, and Tommy Noonan selected four proposals. The artists received stipends, production budgets, technical support, rehearsal time in CURRENT, critical coverage, marketing—and, perhaps most valuably, a festival showing of a professionally produced video to use as a calling card.

The 20/21 Digital Commons began on January 29 with Pain, Trauma, Triumph, in which Anthony Nelson, whose ensemble work is already familiar to ShaLeigh Dance Works patrons, turned a stark box of light into a charged zone between the fear of failure and the fear of success in a moving contemporary solo. It continues with Ayanna Albertson’s Lineage on February 5, followed by Eternal the M.C.’s How Can We Explain This? on February 12 and Johnny Lee Chapman III’s Southern (Dis)Comfort on February 19.

It amounts to a multifaceted but mutually galvanizing collage of distinctly Black experience—of neglected history in Johnny’s work and the personal present in Anthony’s, of the family in Ayanna’s and of racial strife in Eshod’s. “This is something I really wanted to encourage especially poets who are multidisciplinary to think about,” Dasan says. “Lee is a performing artist and photographer and writer; Ayanna has a theater background and is a vocalist. It was important for them to be able to present themselves in a whole way.”

Though Ayanna read poems at open mics in college in Alabama, she had never even been to a slam when she moved back to her native North Carolina and met Dasan, who invited her to give Bull City Slam a try in 2016. Her theater background came in handy—not only did she win, but she also learned that it was a qualifier for a national competition, the Women of the World Poetry Slam. “I was like, wait, where am I going?” she says.

After placing in the top 20 the first two years, she won second place in 2020, just before the coronavirus shutdown. “So technically, on paper, I am the second-best woman slam poet in the world,” she says, laughing. Lineage, which revolves around her poem about the unique, sometimes traumatic experiences of Black families, builds on a self-produced solo show from 2019, Becoming. But The Commons was her first chance to combine all her talents, while discovering new ones, into a “full Black experience.”

“I sing, I do poetry, and I consider myself a D-list comedian,” she says. “So I’d already started that wheel turning. But in the theater world, I’m used to the director telling me what to do, and I have a slam coach. This time, I was producer, I was director, I was writer, I was composer. It gave me this creative freedom that I really liked, but it was uncharted territory at first.”

“Her piece is filled with so much vulnerability and raw emotion, and on top of that, she can sing her ass off!” says Kyesha Jennings, the INDY hip-hop columnist who was embedded with Ayanna, as well as with Eshod, the Cypher Univercity founder whose “visual hip-hop experience” grew out of the turmoil of last summer and features a large cast. Kyesha, always a tireless and caring champion of local artists, got to influence the pieces she was writing about more than ever before.

Johnny, who also got into the spoken word community through Dasan, has been building toward Southern (Dis)Comfort since he left dentistry school at UNC to pursue art. He wrote poems on Tumblr and, after working in commercial photography in Charlotte, ran a photography blog called The Golden Moment. “The vision got its own life with the aid of the videography,” he says. “I’ve tried to do it with my blog, but the resources of the residency gave it more push, and a more concrete feeling I could feel proud of.”

His piece grows out of his work writing about the marginalized histories of North Carolina with the Black on Black Project, and touches on everything from Dorothea Dix and maroon communities to the indigenous tribes of Fuquay-Varina. He was connected with writer Howard Craft for his first artist interview ever, which he found invaluable. “Howard is also a poet and a playwright, and a mentor for someone like Dasan, who I see as a mentor. So it was almost like meeting an elder or ancestor,” he says.

After the artist selection proceeded naturally from Dasan’s contact network, everything else proceeded from the artists. “Their work drove who we sought to connect them with,” says Dasan, who reached out to Courtney Reed-Eaton and Lana Garland because they worked with Black and brown filmmakers in the area. Videographers Wo Agnaza and Devonte Soileau and production manager Angela Brickley made an impact on these pieces that was already evident in the tautly edited second act of Anthony’s performance.

“We created a space that was about them, and not so much about us as a presenter,” Dasan says. “It’s really going to make a mark on them going forward. They’ll see their work in a different way now that they’ve done this, and the message that sends to other young artists in the area is powerful.” So, too, is the message to any presenters befuddled by the homogeny their theoretically open calls for submissions produce. It’s not enough to say you can, but a little you should goes a long way.

To learn more about The Commons festival, visit CarolinaPerformingArts.org/The-Commons.

Anthony “Ay-Jaye” Nelson in Pain, Trauma, Triumph in the first show of The 20/21 Digital Commons. Photo by Wo Imaging.

Chapelboro.com has partnered with the Orange County Arts Commission to bring more arts-focused content to our readers through columns written by local people about some of the fantastic things happening in our local arts scene! Since 1985, the OCAC has worked to to promote and strengthen the artistic and cultural development of Orange County, North Carolina.

Chapelboro.com has partnered with the Orange County Arts Commission to bring more arts-focused content to our readers through columns written by local people about some of the fantastic things happening in our local arts scene! Since 1985, the OCAC has worked to to promote and strengthen the artistic and cultural development of Orange County, North Carolina.