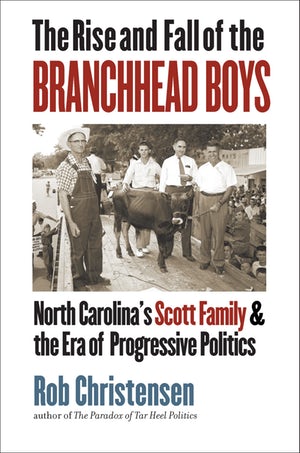

The Scott family.

Too much for one book. Too much for one column.

Five years ago, in “The Political Career of W. Kerr Scott: The Squire from Haw River,” Julian Pleasants chronicled the exceptional life of the only governor of North Carolina who proudly called himself a liberal. Kerr Scott was governor (1949-1953) and U.S. senator from 1955 until his death in 1958. He broke the hold of a conservative Democratic Party establishment and opened the door for the progressive administrations of future governors Terry Sanford, Robert Scott, and Jim Hunt.

Missing from Pleasants’ excellent book was the story of the entire Scott family and its role in North Carolina political life. Former Raleigh News & Observer political reporter and columnist Rob Christensen takes up that task in “The Rise and Fall of the Branchhead Boys.” He follows the Alamance County farm family beginning with Kerr Scott’s grandfather, Henderson Scott (1814-1870) a slave-holding farmer. After the Civil War he became active in the Ku Klux Klan and was briefly jailed as a result.

Missing from Pleasants’ excellent book was the story of the entire Scott family and its role in North Carolina political life. Former Raleigh News & Observer political reporter and columnist Rob Christensen takes up that task in “The Rise and Fall of the Branchhead Boys.” He follows the Alamance County farm family beginning with Kerr Scott’s grandfather, Henderson Scott (1814-1870) a slave-holding farmer. After the Civil War he became active in the Ku Klux Klan and was briefly jailed as a result.

Henderson’s son, Robert (1861-1929) continued the family farming tradition. He spent almost a year in New York state to study modern farming methods. Then, after transforming his own farming operations, he shared his expertise throughout the state, earning the nickname “Farmer Bob.” Active in politics, he served in the state house and senate and unsuccessfully ran for Commissioner of Agriculture.

Robert had 13 children including two important political figures, Kerr (1896-1958) and future powerful state legislator, Ralph (1903-1989.)

Photo by Robert Willett

Christensen does a good job of reviewing and supplementing Kerr Scott’s political career as covered in Pleasants’ more detailed account. He describes how Kerr Scott defeated the favored gubernatorial candidate of the conservative wing of the party in 1948. When in office he adopted a liberal program of road building, public school improvement, and the expansion of government services. Hard-working and hard-headed, direct and plain-spoken, he appointed women and African Americans to government positions and disregarded criticism of his actions. Then, when elected to the U.S. Senate in 1954 as a liberal in a campaign managed by future Governor Terry Sanford, he nevertheless joined with fellow southerners to oppose civil rights legislation.

Christensen’s greater contribution to the Scott family saga is his account of the political career of Kerr’s son, Bob Scott (1929-2009). Young Bob grew up on Kerr’s dairy farm and, like his father, became active in farmers’ organizations, working in political campaigns, including Terry Sanford’s 1960 successful race for governor. By 1964, at age 35, he was ready to mount a statewide campaign for lieutenant governor. But two senior Democrats, state Senator John Jordan and House Speaker Clifton Blue, were already running. Christensen writes, “In some ways Scott had broken into the line.”

Nevertheless, with the help of powerful county political machines, he won a squeaker victory in a primary runoff over Blue.

Scott used his new office to run for the next one, giving hundreds of speeches each year and eating meals of “razor thin roast beef, seventeen green beans, a wad of mashed potatoes and apple pie the density of lead.”

Meanwhile, Christensen notes, “The growing white backlash against racial integration gave Scott reason for caution.” He won the 1968 Democratic nomination over conservative Democrat and later Republican Mel Broughton and African American dentist Reginald Hawkins.

The results of the presidential contest in North Carolina marked what Christensen calls “the breakup of the Democratic Party.” Richard Nixon won; George Wallace was second, and Hubert Humphrey was third.

Nevertheless, in the governor’s race Scott faced and beat Republican Jim Gardner.

The mountains of bitter controversies in the areas of race, labor, student unrest, and higher education administration he confronted are too much for this column to cover.

We will continue in a later column.

D.G. Martin hosts “North Carolina Bookwatch,” Sunday 11:00 am and Tuesday at 5:00 pm on UNC-TV. The program also airs on the North Carolina Channel Tuesday at 8:00 pm and other times.

D.G. Martin hosts “North Carolina Bookwatch,” Sunday 11:00 am and Tuesday at 5:00 pm on UNC-TV. The program also airs on the North Carolina Channel Tuesday at 8:00 pm and other times.