NOTE: This was written in the summer of 1991, as Hubert Davis entered his senior season with the Tar Heels, and as David Glenn became a first-year student at the UNC School of Law. Every word (including the headlines) is from a hardcover, special anniversary collector’s edition of “Carolina Court,” an annual magazine then edited by Glenn and published by Village Sports, Inc., of Chapel Hill.

Carolina Blue Background Gave Davis His Chance

By Dave Glenn

Sixteen-year-old Hubert Davis Jr. wears a blank stare as he gazes out the front window of his family’s white-faced suburban home, tucked away in a serene residential neighborhood in northern Virginia.

It is September 1986. On most afternoons during the past several years, Davis has been launching basketballs at the aging basket on the blacktop driveway out front, nailing jumper after jumper from near and afar under the watchful eye of his best friend and father, Hubert Sr.

But on this day, Davis is inside, alone with his thoughts. He’s waiting for his mother to come home from work, just as he’s done for what seems like every day for the past 16 years. A tear comes to his eye. He feels as if he’s waited this wait and thought these thoughts 100 times in the past month.

Bobbie Davis, who had become half of Hubert’s soul during his young life, never came home that day. She died of cancer in August 1986, in a tragedy her only son refused to accept for a long, long time. For a teenager, this was one big reason to be mad at life. For the next several years, Hubert Jr. felt confused and cheated — hateful toward the expanding world around him. But mainly, and most painfully, he felt as if he had lost one of his two best friends.

If only she could see him now …

At 21 years old, Hubert Davis Jr. is everything his mother and father had hoped he would be. In the past five years, he has turned a Carolina Blue upbringing into an amazing college basketball career that looks like something right out of Storybook Land. More importantly, he has weathered the celebrity spotlight and remained the kind of soft-spoken, self-effacing young man his mother and father taught him to be.

It didn’t take long for Hubert to find out how things worked in the Davis household. When it came to Hubert Jr., dad was the “ruthless dictator” and mom was the softy. “If I wanted something, I’d go to my mom,” Hubert says. “She’d give me everything.” When it came to sister Keisha (KEE-sha), six years his junior, the roles were reversed. In the long run, he says, it couldn’t have worked out better.

“My family was perfect,” Davis says, rising above his usual, reserved tone with a smile. “I’m not kidding. I feel so lucky to have had what I’ve had. We were like the Brady Bunch.

“The respect I have for my mom and dad is just unbelievable. I love the two of them so much it’s incredible. Anybody would. I could talk about them forever. They’re the two kindest people I know. … To me, they’re perfect.”

Everything he’s done, he says, he owes to his parents. In conversation, he refers to them often, in a fun, candid way that can easily slip notice. But almost every answer to every question has a reference to mom — often still in present tense — or dad. When he speaks of them, it is with complete respect, almost reverence. It is, to him, the story of his life.

Born May 17, 1970 in Winston-Salem, Davis entered the world with basketball in his blood, which, looking back, was probably blue. His father, a 6-4 forward who passed on his height and toughness to his namesake, was three years removed from an excellent hoops career at Johnson C. Smith College in Charlotte. It was there that Hubert Sr. impressed a man named Dean Smith with the kind of emotional and competitive play that would become his son’s trademark, under Smith, at North Carolina 20 years later.

Then there was Hubert Sr.’s younger brother, a 17-year-old kid from Pineville, N.C., who was doing things with a basketball that most youngsters just don’t do. Walter Davis caught Smith’s eye, too, early enough for Smith to offer him a scholarship to UNC. Little did Hubert Jr. know at the time, but Uncle Walter’s stellar career with the Tar Heels, and his father’s growing relationship with Smith, would slowly bring about an amazing turn of events that added a Carolina Blue flavor to just about everything baby Hubert came into contact with over the first 21 years of his life.

A look back proves one thing certain: If ever the Carolina fight song applies, if ever there has been a person truly “Tar Heel born and Tar Heel bred,” that person is Hubert Davis Jr.

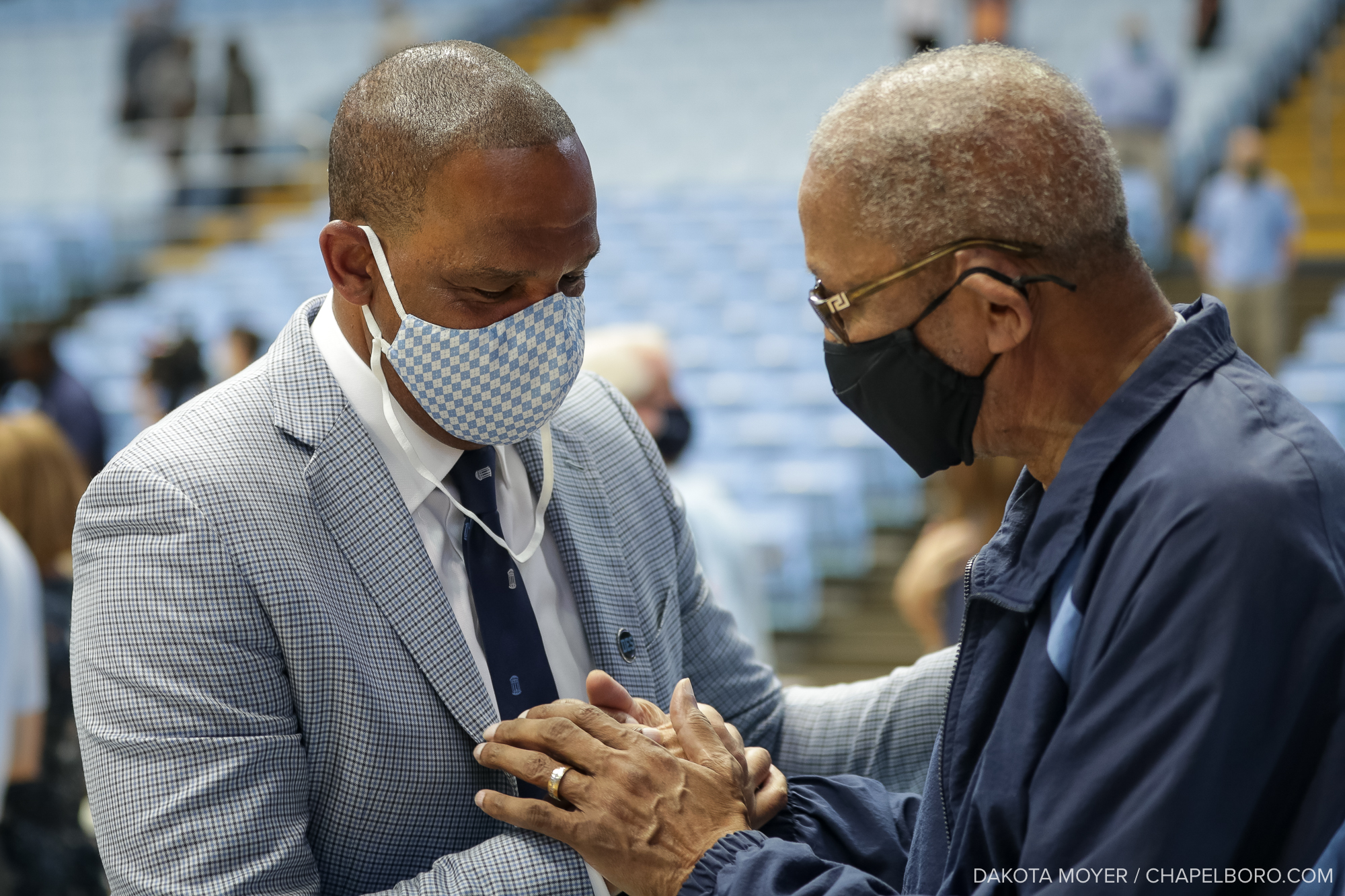

Hubert Davis wears a pin with the letters “DES” on it — for Dean Edwards Smith — during his introductory press conference at the Dean Smith Center on Tuesday, April 6. (Dakota Moyer/Chapelboro.com)

Hubert doesn’t even remember it all. It was 1973 when he first came into direct contact with the Carolina basketball program. Uncle Walter, attending prep school in Delaware just a few hours away from the Davis’ old home in Washington, D.C., often came to visit on weekends. It was there, with Hubert Jr. bouncing around in the background, that Tar Heel assistant Bill Guthridge made his official visit to Walter. After arriving back in Chapel Hill, Guthridge sent a letter to Hubert Sr. and Bobbie, thanking them for their hospitality. Then, he added this playful-but-prophetic declaration:

“At this time, we want to officially begin the recruitment of Hubert Jr.” The Kid was only 3 years old.

The plot innocently thickened three years later, when Uncle Walter invited the rest of the Davis clan to Montreal for the 1976 Summer Olympics. Walter was there representing the North Carolina, er, United States team, which included Smith, the head coach; Guthridge, his eternal assistant; and Tar Heel playing stars Phil Ford, Mitch Kupchak and Tommy LaGarde. The Davises made the long journey to Canada in their old Mercury Marquis — “a real boat,” says Hubert — leaving newborn Keisha with Bobbie’s parents in Winston-Salem.

While the stay in Montreal remains mostly a blur to Hubert, the little kid in him remembers one thing for sure: The red, white and blue team won it all. “It was an incredible thrill,” Hubert says, thinking back to his days as a ripened 6-year-old. “That really was the first time I started thinking about going to North Carolina to play basketball.”

While the trip to the Great White North marked the sketchy beginnings of Hubert’s early fascination with Carolina basketball, it turns out there wasn’t much juice to the now-famous tale about young Hubert’s 13-hour ride back from the Olympics. In fact, Olympic gold medalists or not, it was all pretty simple: mom and dad up front, Walter and Phil in the back, and Hubert in the middle. “We slept the whole way,” Hubert says. Well, almost.

“For a little while, Hubert was jumping around in between Walter and Phil in the back seat,” says Hubert Sr., a sharp-minded wit who understandably has a better recollection of these early days. “The expression on his face was amazing. We stopped in Rocky Mount (Ford’s hometown) and Chapel Hill before we came back home. Walter and Phil were great. For three days, everywhere they went, Hubert was right there with them.”

Back at the Davis’ home in Alexandria, Hubert started mounting blue things on the walls of his bedroom. Carolina fever was spreading rapidly. First, it was just a few pennants. Then a picture of Walter, a picture of Phil. Finally, he says, he even got a photo of Smith “just sitting there coaching.” Later, he painted his bedroom (what else?) Carolina Blue. He even got his own picture taken, with Walter’s Olympic gold dangling heavily from his skinny neck and wearing an ear-to-ear smile. Nowhere in his innocent eyes could he have seen 15 years down his fairy-tale road, when he would earn a gold medal of his own as the leading scorer for the U.S. team in the World University Games. Not in his wildest dreams. Never in a million years. Not yet, anyway.

Hubert was soaking up the atmosphere, all right. He was surrounded by basketball. Hanging in his crib, probably. At 3 and 4, he tagged along with dad to youth league centers, where Hubert Sr. coached 10- to 12-year-olds. At 7, there were a few trips to see Walter in UNC’s Carmichael Auditorium, where he got to hang around in the locker room with the Tar Heel players after the game.

“It was around then that he started saying, ‘Dad, that’s where I wanna go. Dad, that’s where I wanna go.’” says Hubert Sr., who fed the growing desire by allowing Junior to attend the Carolina basketball camp. Soon after, there were a few years’ worth of trips to see Kupchak, a good friend of the family, in his professional playing days with the NBA’s Bullets.

“One time, I went to see the All-Star Game there,” Hubert says. “I was in the locker room with Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, Dr. J, Larry Bird, Earvin Johnson. It was just incredible.”

Starry eyes aside, it didn’t take long for Hubert Jr. to learn that basketball ability is not a birthright, no matter what the family name. Watching is learning, he discovered, but the only way to become a great basketball player was to play an awful lot of basketball. So he did.

With one goal in mind, the same blue and white dream thousands of little boys have every year, Hubert Jr. learned the game of basketball on the blacktop and hardcourt of northern Virginia. From the slanted driveway out front to the spacious arena at nearby Lake Braddock High School, he wondered of UNC, “Are they watching? Will I get my chance?” Up until the very end, he wasn’t sure. All the while, Hubert Sr. watched and helped his son grow, on and off the court. A few words of encouragement here, a little piece of advice there. In the process, his boy became a man. Somewhere in between, a basic philosophy of basketball was handed down from generation to generation. And these rules don’t bend.

Rule No. 1: Play hard and study harder.

Hubert was extremely active as a youngster. At his mom’s urging, he developed a fascination for the cello and played from third grade through 10th. He also played tennis, baseball and football. But he never strayed from his educational goals, not even for the hardcourt. “I didn’t let Hubert go to a lot of basketball camps,” says Hubert Sr. “I used to tell him you can have the basketball skills, but if you haven’t applied yourself academically, the skills won’t help you at all.”

Rule No. 2: Never give up and always do your best.

Hubert Jr. eventually was allowed to go to the prestigious Five-Star camp after his junior year. After one day against prep superstars Billy Owens, Alonzo Mourning and Malik Sealy — “one of the first times I played against anyone over about 6-4,” Hubert says today — the shy guy from Burke, Va., desperately wanted to come home. In cases like this, Hubert Sr. says he relies on one rule of thumb when it comes to his distant son’s well-being: When the phone doesn’t ring, everything is OK. On this occasion, of course, the Davis’ phone was ringing off the hook for two days in a row: “Dad, these guys are all better than I am. I’m playing terrible. I shouldn’t even be here.” Senior’s response: “Don’t worry about it. Who cares? Everybody has bad days. Just go out there and do your best.” For the next five days, the phones were silent in the Davis household. And when dad drove to Five-Star to pick up his son on Sunday, he found before him a newly crowned member of the camp All-Star team.

Rule No. 3: Basketball is a physical game. Get used to it.

Hubert Sr. played inside in college, and he didn’t mind a little contact under the boards. After all, God gives elbows, knees, hips and shoulders for a reason, right? “When I was growing up, he was much stronger than I was,” says Hubert Jr., who found himself plastered across the Davis’ driveway on more than a few occasions. “He’d bump me, foul me, knock me down. I mean he was just like Bill Laimbeer. He used to kill me. I remember I used to get so mad at him sometimes. I wouldn’t talk to him for a couple of days.” Too bad, kid, because …

Rule No. 4: Between the lines, basketball is all business.

Father and son alike have no friends on the basketball court, including each other. “There is no friendship out there,” says dad, who looks as if he could throw a pretty mean scowl. “You throw all that away when you’re out there competing.” Hubert Jr., a quiet, affable sort in conversation, also takes on a new persona when the topic is competition. “When I’m on the court, I don’t know why, but something changes in me,” he says. “I’ll get so competitive that I’ll talk to you while I’m playing you. I’ll be mean to you. I don’t like you. I’m not scared of anything. There’s something about playing basketball that makes me feel like I can do anything.”

Rule No. 5: Don’t worry, be happy.

This has been a big change for Hubert Jr., a guy who says he’s still shy and uncomfortable around people he doesn’t know very well. “It’s been a real key for me,” he says. “My first two years were so stressful, I didn’t have fun. My dad’s right. Have fun out there. Smile if you want to smile. Yell if you want to yell. If you’re 10-for-10, you’re having fun. But if you’re 0-for-10, you should still be having fun, too. If you feel like jumping up and down, do it. If you feel like waving a fist in someone’s face, do that. If it gets you going, go for it.”

Hubert Davis greets friends and family after his introductory press conference at the Dean Smith Center on Tuesday, April 6. (Dakota Moyer/Chapelboro.com)

Armed with the rules of sport, Davis excelled on the hardcourt and the gridiron at Lake Braddock. The latter fact has become a famous “Did You Know?” among Carolina sports fans, the one about Davis catching passes from current Tar Heel quarterback Todd Burnett. But there’s more.

In football, the Burnett-Davis combo led its squad to the first seven-win season in the 15-year history of a school that’s packed with about 5,000 students in any given year. Davis not so quietly caught a school-record 58 passes for 666 yards and nine touchdowns while earning all-state honors. And it gets better.

On the hardcourt, Davis was well on his way to finishing his career as the school’s all-time leader in scoring (1,604 points in 70 games), field goal shooting (62 percent) and foul shooting (87 percent). During his senior year, the team went 24-2. Davis had 15 games of 30 or more points, more than all of the players (combined!) in the history of the school.

Yet, at this point in his blossoming two-sport career, Davis still was more famous for the six-pointer from the 50-yard line than the three-pointer from the 21-foot line. Strange but true: Davis, unwilling and unprepared to change his game for the experimental three-point rule, attempted only four treys during his entire senior season. Stranger but true: He made only one.

Maybe that shocking revelation helps explain the bizarre turn of events that followed. Dreams don’t always come true, and Hubert Davis’ heartfelt desires to play basketball at UNC weren’t necessarily enough for this story to have a happy ending. Even with all of his high school accolades, his family connections, seven summers of Carolina basketball camp, and his most sincere hopes, Davis wasn’t a sure bet to become a Tar Heel.

For one, Dean Smith wasn’t sure he was good enough. And that’s a very big one.

So it was on a Friday afternoon in September 1987, as Hubert Sr. and Smith sat down in the Davis’ living room and talked about the future while the lad in question scurried about, preparing for another football game as the next four years of his life hung in the balance.

Smith, as is his wont, talked straight with his old friend. He called Hubert Jr. “a fine gentleman” and related a story about John Crotty, a Tar Heel reserve from 30 years before whose son John had recently signed with the Virginia Cavaliers. Smith compared the situations, saying he thought Hubert could be a good player at a mid-Division I program, just as he thought the elder Crotty could have been in similar circumstances. He said he could make no promises, that he would feel bad if Hubert went to Carolina and had to sit on the bench for four years. In the end, he could say no more.

“I told coach not to worry about that,” says Hubert Sr. “I told him, Hubert has a goal. A dream of going to North Carolina. It appears that he has done what he needs to do to be put into consideration. You’re here and you’re considering him.

“All I ask and all Hubert asks if that he be given a chance. If he’s given a chance, then whatever falls out of that chance falls out. You don’t have to make any promises to me.”

Hubert Sr. never told his son about that conversation. It was during Hubert’s sophomore year at UNC, two years later, when he finally learned of the meeting of the minds.

“It was funny because I kept seeing all those articles about Coach Smith telling my dad I shouldn’t play at North Carolina,” Hubert says, still a but amused by the whole scam. “My dad never, ever told me that. Now I know, but my dad never told me. I would always ask him, Dad, do you really think Coach Smith wants me? And he would say yes. Every time.

“He would say, yes, Hubert, I really think you can play at Carolina,” Hubert says, laughing while trying to mimic what must have been his dad’s deep, serious tone. “Yes, Hubert, he really wants you. Yes, Hubert, he really wants you. Who was he trying to kid?”

Hubert Davis did a lot of growing up during his first three years at UNC. On the court, he quickly impressed the coaching staff with quickness, athleticism and shooting ability unattributed him in previous evaluations. And, as his playing time increased steadily, so did his scoring totals, from 3.3 to 9.6 to 13.3 points per game. “It shows what I know,” Smith likes to say, assessing one of his few poor judgments with infallible hindsight as his guide.

In Chapel Hill, the Hubert Davis story became one of a self-made basketball player, a Horatio Alger in sneakers. There was plenty of hard work, the same rigorous routines every Carolina player goes through. And then there was that little bit extra. The Smith Center workouts before classes, between classes, after classes. The 500 three-pointers a day during the offseason. The thousands and thousands of free throws.

Davis certainly has shown a liking to this crazy three-point thing, adapting quickly as a freshman and gradually developing into one of the top three-point shooters in the nation. In the process, he’s also joined an exclusive group of athletes (Hubie Brooks, Michael Cooper, Warren Moon and Lou Piniella, to name a few) who sound as if they’re getting booed by the home crowd every time they do something well. “Huuuuuuu-bert,” yell the Smith Center faithful, every time Davis uncoils to throw in yet another lightning bolt from afar.

Last year, he led the ACC and ranked with the nation’s best by hitting a school-record 48.9 percent from beyond the arc. Ironically, Davis’ accuracy mark broke the record previously held by former Tar Heel Jeff Lebo, the guy Davis credits most with his own three-point success. “He taught me how to spot up and shoot quickly, without having to look down at my feet,” Hubert says. “He spent a lot of time practicing with me, helping me get a feel for where I was on the floor.”

As a junior, Davis finished second among the Tar Heels in scoring (to good buddy Rick Fox) and really warmed up down the stretch. In the last 15 games of the season, including the pressure-packed run to the Final Four, Davis led the Tar Heels in scoring eight times, shooting 58 percent from the field and averaging a hefty 16 points per game.

More importantly, Hubert says, he’s found a new attitude — one that will be able to help him long after he gives the arms-up, three-point signal for the last time. Last year, he became a Christian. He says it’s helped him put basketball, and life, in a new perspective.

“My freshman and sophomore years, I was hurting real bad,” he says. “I wasn’t getting much playing time. I was away from home. I was homesick, and I was wondering where my mom was. I would take basketball too seriously. If I had a bad game, it would affect my school, affect my attitude.

“Now, I’ve become more relaxed and I’ve learned to be able to have fun again. Basketball means a lot to me, but it’s not everything. It’s just a game. If I have a bad game, I feel bad but then I’m done with it and I can go on with other things.

“That’s the way life is sometimes. Like with my mom. I still don’t completely understand it, but I just thank God for giving me the best mom in the world for 16 years, because I think anyone in the world would love to have had a mom like mine.”

Hubert Davis thinks back to his sophomore year in high school, about 15 months before this 15-year-old would see his mother for the last time. He was playing for Lake Braddock in the basketball district championship game. As always, his mom was in the stands.

“We won the game, and I got MVP or something, so I was the last one cutting down the net,” Hubert says. “I remember looking for her in the crowd. Finally, we kind of locked eyes on each other.

“I will never forget the picture of her face. She was so proud of me. She didn’t even have to say anything. I could just tell. I almost started crying right there, with the net in my hands.

“Now, every time I think of her, I picture her with that same look on her face, like she’s saying, Hubert, you’re doing OK. And I hope she’s still looking down at me saying that same thing today.”

David Glenn (DavidGlennShow.com, @DavidGlennShow) is an award-winning author, broadcaster, editor, entrepreneur, publisher, speaker, writer and university lecturer (now at UNC Wilmington) who has covered sports in North Carolina since 1987.

David Glenn (DavidGlennShow.com, @DavidGlennShow) is an award-winning author, broadcaster, editor, entrepreneur, publisher, speaker, writer and university lecturer (now at UNC Wilmington) who has covered sports in North Carolina since 1987.

The founding editor and long-time owner of the ACC Sports Journal and ACCSports.com, he also has contributed to the Durham Herald-Sun, ESPN Radio, the New York Times, the Washington Post, Raycom Sports, SiriusXM and most recently The Athletic. From 1999-2020, he also hosted the David Glenn Show, which became the largest sports radio program in the history of the Carolinas, syndicated in more than 300 North Carolina cities and towns, plus parts of South Carolina and Virginia.