Story by Andrea Kelley, Graphics by Rachel Wock

As the sun rose over the Atlantic on May 15, 1936, Unaka Jennette turned out the light for the last time.

He ran his hands over the lens he had so lovingly cleaned for 18 years, took one last look around the tower, climbed down to the watch room, walked through the swinging doors and descended the 269 stairs for the final time.

The Cape Hatteras Lighthouse was officially decommissioned.

That night, an electric light shone baldly out from a steel skeleton tower in the woods west of the lighthouse.

Now, 85 years later, the National Park Service is restoring the lighthouse to the way it looked in Unaka Jennette’s day.

THE HISTORY

The Cape Hatteras Light has been a beacon for sailors for more than 200 years.

No stretch of the Atlantic coast is more dangerous to navigate than the waters off of Hatteras Island. Here, the cold Labrador current comes down from Canada and mixes with the Gulf Stream’s warm Caribbean water. This creates unstable weather conditions and fantastic storms.

Cape Hatteras is also the easternmost point on the Atlantic Coast. Its elbow-like point juts into the sea and is surrounded by Diamond Shoals, which is a trio of constantly shifting sandbars that stretches nearly 15 miles out to sea.

Many ships have run aground here and been pounded to oblivion by the relentless waves, earning this strip of coast the nickname “The Graveyard of the Atlantic.”

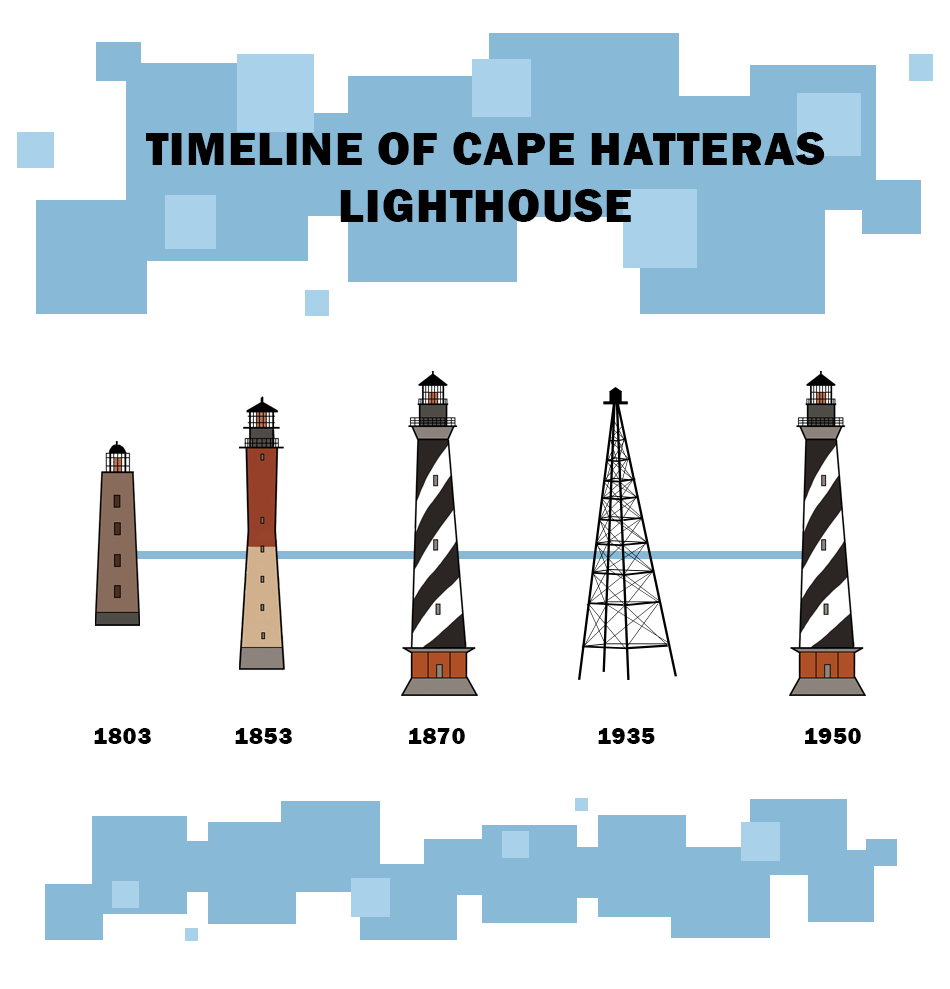

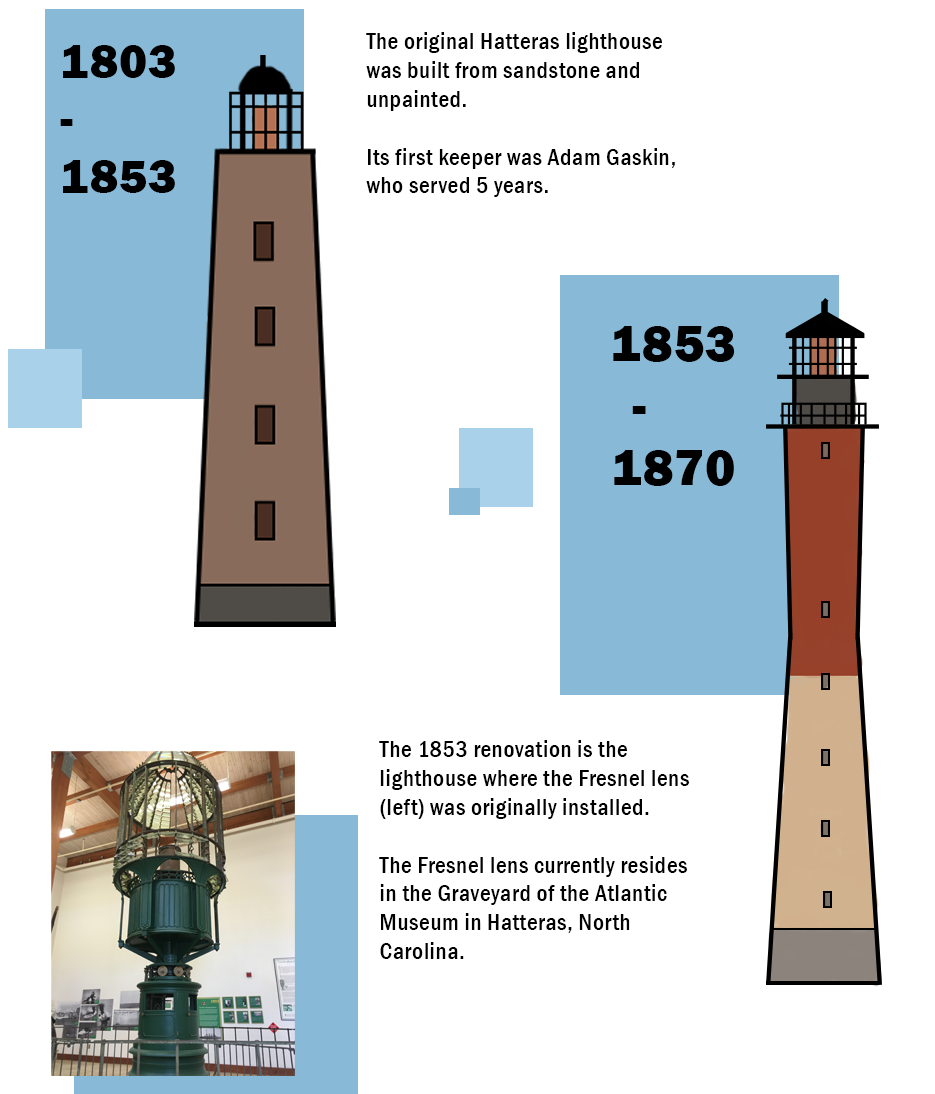

In 1803, a lighthouse was built on Cape Hatteras to warn sailors of the shoals. At 100 feet tall, it could be seen almost 18 miles out in clear weather, but the light was too dim to see during storms.

The lighthouse was raised to 150 feet in 1854, and a first-order Fresnel lens was installed over the whale oil lamp. Fresnel lenses are composed of multiple prisms that focus the light into one strong beam, substantially increasing the light’s brightness.

During the Civil War, the lighthouse had been used as a lookout tower by both Union and Confederate troops, and it sustained structural damage. The ocean was also encroaching on its base. Something needed to be done.

Engineers decided it would be cheaper to build a new one than to refurbish it. The Light-House Board agreed, and drew up plans for a new lighthouse, but this time, they would do it right.

THE COMMUNITY

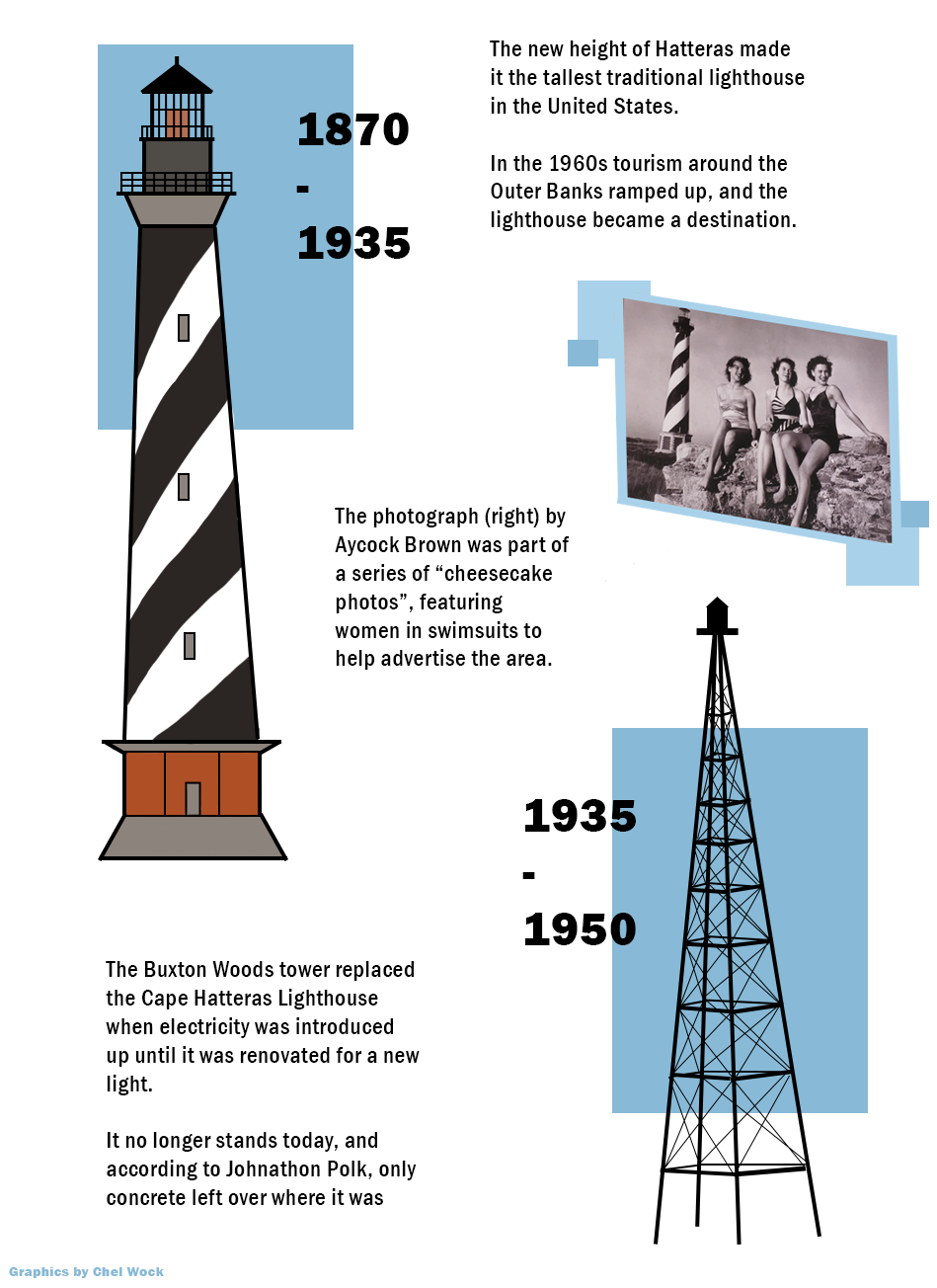

The new Cape Hatteras Lighthouse was finished in 1870, and stood 198 feet, the tallest lighthouse in the country. The double-walled brick tower was topped by a first-order Fresnel lens and could be clearly seen 20 miles out to sea.

“The Cape Hatteras lighthouse was built to be the lighthouse of all lighthouses,” Jonathan Polk, a supervisory park ranger with the National Park Service, said. “Congress and the U.S. Lighthouse Service realized that Cape Hatteras was one of arguably the most dangerous areas of the coast – not just in the Atlantic Coast, but some will say in the entire world.”

Three years later, it was painted with black and white stripes to serve as a daymark to distinguish the lighthouse from the land and from other lighthouses. The stripes have become iconic.

“I don’t think, certainly not in the 1870s, 1880s, up until the 1900s, that there was any cultural significance much. It was a functional structure,” said John Havel, a member of the Outer Banks Lighthouse Society and self-taught Cape Hatteras Lighthouse expert.

“But yet, the Lighthouse Establishment felt it was that important… to build such an incredibly beautiful structure. It’s an icon for America.”

Inspectors, supply ships, and mail boats stopped at the lighthouse. The lighthouse keepers sometimes hosted guests overnight, and would even take them up in the lighthouse if they had time.

Maintaining the lighthouse took a lot of time, but the Cape Hatteras Lighthouse always had a principal keeper and at least two assistant keepers and their families living on site to divvy up the work.

Every morning the keeper on duty would put out the light, clean and polish the prisms in the lens, and pull the protective cover over it. He would let down the curtains hanging in each of the 24 windows and head out to wash the panes. The families were busy keeping everything else running smoothly – working in the garden, tending the livestock, and chopping firewood.

In the evening, the keeper would lug kerosene up to the light in five gallon containers.

“The lighthouse keeper’s life was not a fun life,” Havel said, “but they were incredibly respected, one of the highest respected in their community.”

After the lighthouse was decommissioned and the Jennettes moved on, the tower sat empty. Over the next decade, the lighthouse was vandalized and fell into disrepair. Windows were broken and prisms from the Fresnel lens were stolen.

By the end of World War II, the beach had built back up and the lighthouse was no longer in danger of being swept away. The community clamored for it to be repaired and relit.

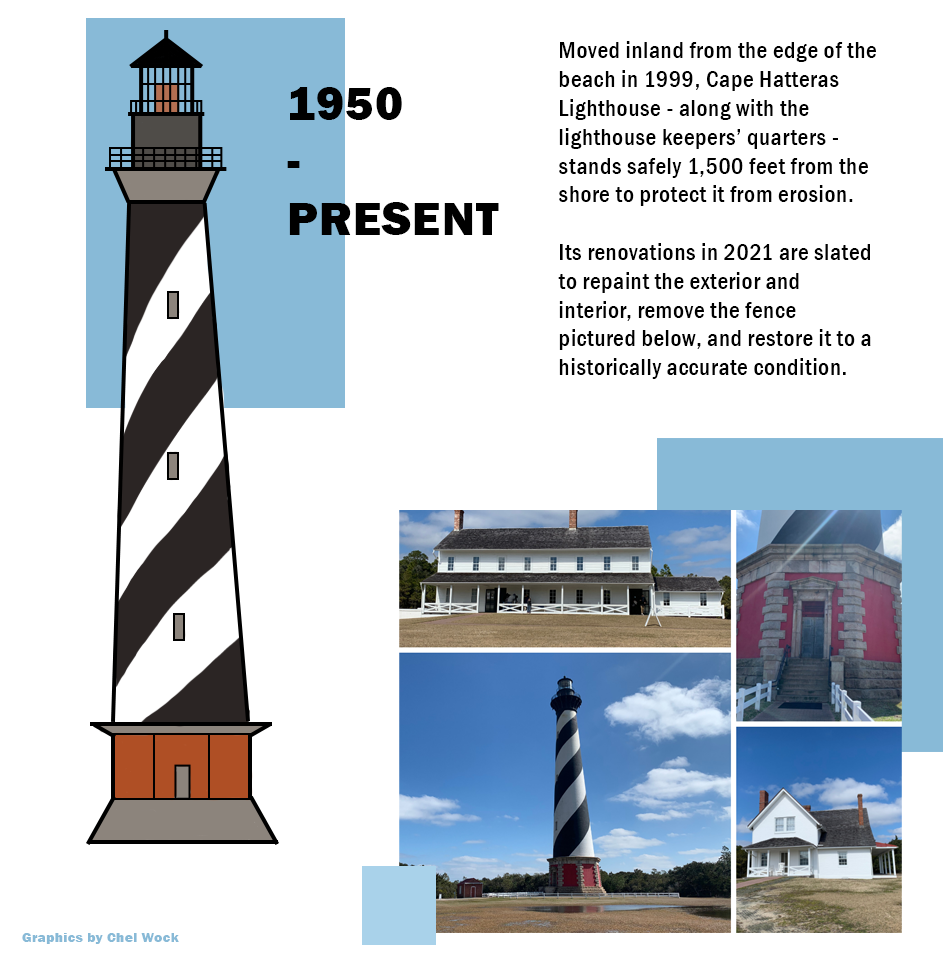

The lighthouse was recommissioned on Jan. 23, 1950. Cape Hatteras had its light back.

In 1953, the National Park Service created the Cape Hatteras National Seashore and took over maintenance of the lighthouse.

THE MOVE

By the 1980s, erosion had come back with a vengeance. The waves were coming within a few hundred feet of the lighthouse base, and the government decided moving the tower might be a viable option. Work began in 1999.

The lighthouse’s foundation was removed section by section and replaced with steel beams. Hydraulic jacks lifted the beams, giving the lighthouse a six-foot boost.

Steel tracks were placed under the lighthouse and extended partway down the new road.

One by one the steel beams under the lighthouse were set on special rollers, called “Hilman rollers,” that sat on the steel tracks. Additional jacks were set up behind the beams to push them horizontally along the track, moving the lighthouse in five-foot increments. The beams were then pulled up from behind the lighthouse and added back to the front of the track.

“The process was so slow and careful that an onlooker could barely see the lighthouse moving,” Cheryl Shelton-Roberts, a historian who co-founded the Outer Banks Lighthouse Society, said in her booklet detailing the move.

But move it did, and three weeks later, on July 9, the lighthouse ended its 2,900-foot journey.

A new four-foot thick concrete foundation had been laid in preparation for its arrival. Over the next few months, the lighthouse was slowly transferred from the steel beams onto a brick “infill,” which consists of five-foot tall brick columns that connect the lighthouse’s base to the foundation.

The last brick was laid on Sept. 14. The lighthouse had made it.

THE RESTORATION

This summer the lighthouse is undergoing one more change – this time, it will be a historical restoration.

NPS has wanted to repair the lighthouse for several years, but had to compete for funding with the other 400 parks in the system.

“That speaks to the importance of the lighthouse and its significance that we were chosen to receive the funding for it,” Jami Lanier, cultural resource manager for Cape Hatteras National Seashore, said. The park received $18.7 million to complete the project.

The tower will get a complete overhaul, starting this month. The NPS did a hazardous materials survey in preparation for the restoration and found lead paint on the inside of the tower, so an interior paint job is first on the agenda.

Other repairs will include fixing or replacing metal, windows, and stonework. Design plans won’t be finalized until late summer, and construction is slated to start in the fall.

Lanier estimated that the project would take about two years to complete, but a historic restoration comes with its own set of challenges.

“If you’re doing specialized work, like recreating a historic window, those types of things can take longer than just going out and buying a window,” she said.

The other half of this project is restoring the lighthouse’s character-defining features, which are elements that the lighthouse had during its “period of significance” from 1870 to 1936.

Some of these features are decorative, like the cast-iron pediments that used to top six of the lighthouse’s seven windows. Others are functional, like the wooden doors that used to be inside the vestibule and up in the watch room.

One of the biggest undertakings will be a replication of the original ironwork around the top of the lighthouse and the cast iron fence that surrounded its base.

“That’s what I fell in love with, is the ironwork,” Havel said.

“If you go to Bodie [Lighthouse], Currituck, and the others, you will notice the railing posts are just pipes with holes on the top,” he said, “but here they’re floral, beautiful Victorian.”

The ironwork and fence won’t be made out of the same material as the originals because of the high product costs and maintenance considerations, but “they will be cast exactly as the original ones were,” Havel said.

The only part of the restoration that’s still uncertain is whether to include a reproduction of the Fresnel lens.

“He will constantly remind them that a lens should be included,” Shelton-Roberts said. “That’s the soul of the lighthouse.”

Fresnel lens or no, the lighthouse will soon look like it did under Unaka Jennette’s meticulous care – a beacon standing proudly against the sky, guiding sailors home.

Stories from the UNC Media Hub are written by senior students from various concentrations in the Hussman School of Journalism and Media working together to find, produce and market unique stories — all designed to capture multiple angles and perspectives from across North Carolina.

Stories from the UNC Media Hub are written by senior students from various concentrations in the Hussman School of Journalism and Media working together to find, produce and market unique stories — all designed to capture multiple angles and perspectives from across North Carolina.