Recycling plastic bottles or containers as an individual is important for improving your environmental impact and awareness of waste. But despite many individual efforts, a systemic change is needed to stop much of that plastic waste from still ending up in landfills or nature.

A UNC researcher is looking to disrupt that system by making plastic more valuable and reusable – and, in turn, creating more reasons for waste companies or organizations to recycle it.

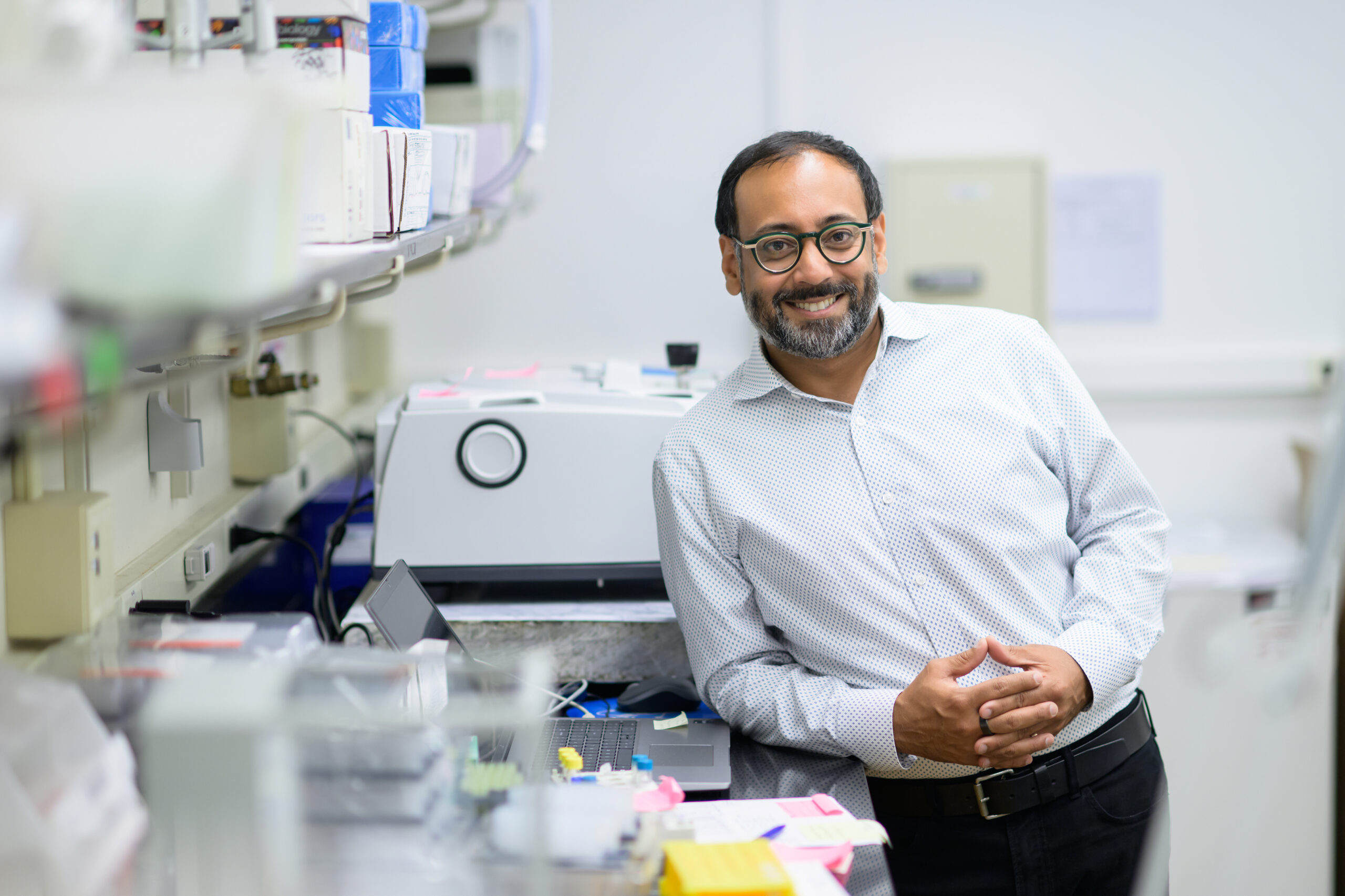

Frank Leibfarth, an associate professor in the chemistry department at Carolina, says one of his lab’s goals is to make the plastics economy more sustainable. His research studies the materials that make up plastics, specifically polyethylene and polypropylene. Those are byproducts of refining crude oil and can be found in everything from packaging to bottles to toys.

Leibfarth says plastic is a critical part to modern life, but it is clear that too much plastic waste is being created. Some of that single-use plastic gets sorted into recycling, but he says most plastic in the U.S. still ends up being thrown away or re-enters the environment as pollution.

“It’s really good to throw your plastic container into the recycling bin, but less than ten percent of what you throw in that recycling bin gets recycled,” says Leibfarth. “And one of the reasons [of that] is because plastics’ recycling is not an economically viable process for most plastics. The recycling company – or the city, county or state government – has to actually pay extra money to see that recycling happen.”

Leibfarth says between the vast dependency we have on plastic and the inefficiency of other materials, there’s no obvious alternative to take its place.

“If we switch from plastic packaging to other forms of packaging – glass, aluminum, paper, etc. – that’s about five and a half times the water usage we need in producing those materials,” he says. “It’s about five times the weight, which leads to much higher transportation costs, much higher petrochemical usage for fuel to transport that around, and about two times the energy consumption. So, plastics are important because the alternatives are, in many ways, worse. But what those numbers don’t account for are the societal cost of all the plastic waste that we’re producing.”

To address that waste, Leibfarth’s lab aims to change the system at both ends: firstly, at how that plastic waste could still be recycled, and secondly, around the type of plastic that gets used for items.

Leibfarth’s research focuses on finding reagents, or specific molecules, to react with a product’s polymers and change that plastic into a different type of plastic. During testing, the team takes plastic waste and feeds it through an extruder – which the chemist describes has a similar function to a hot glue gun – with the reagent mixed in. When it comes out, it’s a new material and one that is often more durable than single-use plastic.

“We can make a material that was polyethylene, like a milk jug, and turn it into a high-strength elastomer that has about five and a half times the toughness of polyethylene,” says Leibfarth. “And this is a material analogous to [one] called Surlyn, which is used in really high-end packaging and is the second layer in golf balls because it’s really resilient and tough.

“A golf ball is worth a lot more money than a milk jug,” he continues. “So hopefully, if we can continue to improve this process and get it to where we can implement it, we can derive value from that using plastic waste as the starting material – which is effectively free.”

Frank Leibfarth (right) and Erik Alexanian demonstrate the strength of a piece of a newly developed thermoplastic by stretching it. (Photo via Jon Gardiner/UNC-Chapel Hill)

The long-term goal for Leibfarth and his team is to change the plastics economy to make it so when something is created, it’s more guaranteed to be upcycled into a new product once its initial use is finished. In the short-term, however, the goal is making the successful reagents more accessible, affordable, and easily applicable. But the lab’s hope is that by enacting a change within the existing plastics infrastructure and industry, it could lead to a more attainable impact than searching for an entirely alternate way to make plastics.

Leibfarth describes that as a circular economy – which aligns with both the basic goals of recycling and the broader goals of reducing climate change and pollution.

“We take this crude oil up from the ground, we spend a lot of energy to make it into plastic… that carbon embedded in there, we should use that more than once,” says the UNC researcher. “We should ideally have that in a circular economy, where we can use that over and over and over again. That’s ultimately our goal and really what drives us.”

Leibfarth’s research lab recently learned of some added support toward that goal. He was named the inaugural faculty fellow for UNC’s new Institute for Convergent Science. The initiative helps innovative Carolina community members be better set up for success in their development of intellectual property, translation of research into real-world solutions, and launches of products. The fellowship is set to last five years.

Photo via UNC Department of Chemistry.

Chapelboro.com does not charge subscription fees, and you can directly support our efforts in local journalism here. Want more of what you see on Chapelboro? Let us bring free local news and community information to you by signing up for our biweekly newsletter.