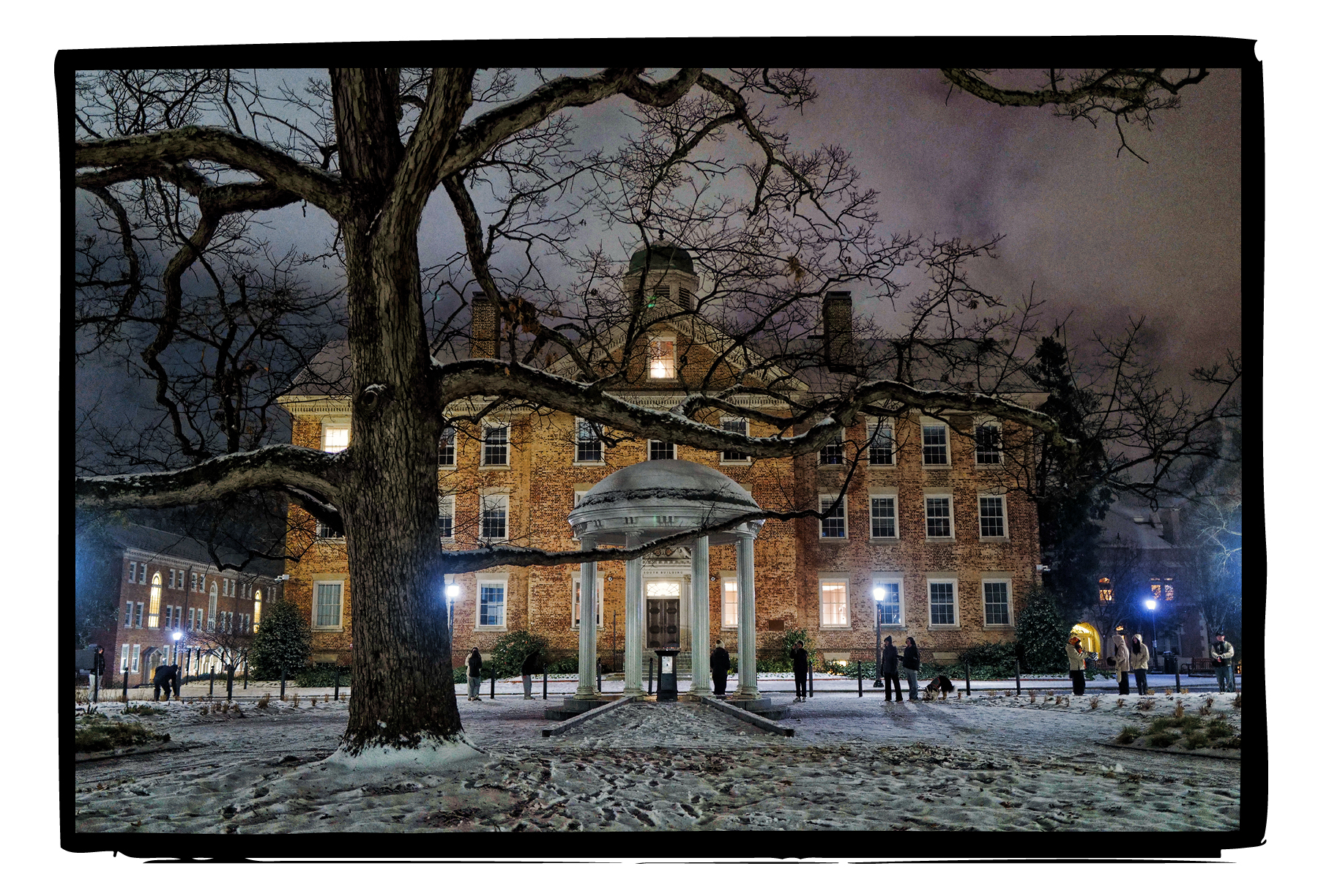

UNC students return to class this week to begin the spring semester – and as always, there is an ongoing debate over what should and shouldn’t be taught in the classroom. Professors say they are feeling pressure to avoid discussing issues of structural inequity – and to focus their attention only on teaching those skills that measurably translate into better jobs with higher pay.

But experts in education say it is the immeasurable lessons that actually make people more successful in the long run – especially in fields you might not expect, like medicine.

“We are obligated by our accreditation authorities to discuss inequities, health disparities, structural violence, structural vulnerability, so our students are prepared to provide informed, empathic, up-to-date care,” says Sue Estroff, who teaches social medicine at UNC and sits on the university’s faculty executive committee. “And the idea that the central tenets of our curriculum are somehow to be erased, from the kind of education that health professionals for the next generation need, is pretty daunting.”

Meg Zomorodi agrees. She also sits on the faculty executive committee – and she teaches at the UNC School of Nursing, where she says it is essential for students to learn how to empathize with patients who walk in the door.

“We’re trying to talk about ways that we can engage patients, ways that we can manage conflict amongst the team, and (equity) creeps up in those dialogues, because it needs to,” she says. “And to not be able to answer some of the questions the students are asking, that is especially challenging as a faculty member. How do I word that — and then also say that this is important, that we need to learn it — when I actually can’t have it in the space that I’m supposed to be in?”

Zomorodi and Estroff say the pushback against discussing equity can have a significant negative impact on academic freedom, just as much in medical school as in any other field.

And as the spring semester begins, they also agree that the most impactful things one can learn in a classroom often have no direct impact on the amount of money a student will end up making in their career. But those lessons do make students better able to provide for the patients, the clients, the customers, and the fellow human beings they will serve.

“I tell (my students) that who they are, and how they are, is as important as what they know,” says Estroff. “So we do reflective writing. We have a humanities and social sciences and bioethics core. You may not see a ‘return on investment’ in your salary, but those things are absolutely essential…

“We (even) take our med students up to the Ackland Art Museum to work with the docents there, to think about race or to think about gender. And if we (insist on asking) ‘how much more are you going to make a year because you went to Ackland,’ then I think we’re really in trouble.”

Zomorodi agrees, saying her students can be a different type of provider because of that experience – which translates to other UNC students’ experiences too.

“That ability to communicate and relate with each other, to have a dialogue with someone that you may or may not fully agree with – these are very important skills that could be lost if we don’t think about it in that way,” she says. “My best students are students who blend the sciences and the humanities. I have students who are actors. I have students who are communications majors, who have wonderful careers in health care because they’re able to connect with people in a different way than someone who might have taken that traditional path. They bring a unique skillset.”

But Estroff and Zomorodi agree that the skillset can be taught. When asked to share their “a-ha moments,” where they see the light bulb go on for students in ways that wind up being transformative for their future careers in healthcare, they described lessons far removed from the standard views about what gets taught in medical school.

“I’m teaching a course for first-years, part of the new Triple-I curriculum,” Zomorodi says. (“Triple-I” stands for “Ideas, Information, and Inquiry,” a required course for first-years.) “I brought in a faculty member in the School of Social Work (who) shared the fact that the highest predictor of your health is your zip code. There was a student in the front row who had never heard that concept before, and she came up afterwards and said, ‘I need to learn more about this…’

“And then at the end of the semester,” she continues, “the student came up to me and said, ‘I just want you to know what that experience was for me. My whole career path is going to be different now.’ She’s now going to probably go and do something great that I haven’t even seen yet.”

Estroff says her memorable moment also came from a first-year seminar, on difference and disability.

“I sent (students) out to do an accessibility audit of the campus, and I was blown away by how engaged they were,” she says. “They were measuring doorways, and they were looking at how long the automatic doors open, ‘could you get into this place to get food,’ and so forth and so on – and I was blown away by how engaged they became in thinking about what accessibility really is…

“That sense of learning together, learning out of the classroom, is key. We do the same thing with medical students: their first assignment is to write their own personal illness narrative, how they learned about being sick and what their experiences are – because they’re going to be the narrators for other people’s illnesses, (so) we want them to narrate themselves first.”

Estroff’s memory reminds Zomorodi of her own experience watching students – medical students, in this case – learn to see the world through others’ eyes.

“I have inter-professional teams of health students go into patients’ homes,” she says, “(and) before they went into one home, (someone said) ‘no wonder this person is sick, they never go to their appointments.’ (But) when they went into this person’s home, they realized: this patient had a lack of transportation, they had to call a van to bring them to their appointment, their neighbors knew they were going to be gone all day, (and) so they would rob his house. So he had a choice between staying at home and protecting his stuff, or taking care of his health. He didn’t have a choice, he had to stay home…

“That left that student wide-eyed: ‘this is what my patient is going to be experiencing.’ And that person will be a very different provider, because of that opportunity to engage and to build and to learn. And that exposure outside of your own little microcosm is the point of the future of higher education, that we need to build upon.”

Sue Estroff and Meg Zomorodi made those comments during a panel on the State of Higher Education in December’s Forum on the Hill. Listen back to that full panel, and 14 others, at Chapelboro.com/ForumOnTheHill.

Chapelboro.com does not charge subscription fees, and you can directly support our efforts in local journalism here. Want more of what you see on Chapelboro? Let us bring free local news and community information to you by signing up for our newsletter.