UNC is 225 years old, and for many of those years there have been different causes taken up by student activists using their voice to protest national policies, campus administration priorities and even change state laws. That happened just over 50 years ago regarding the Speaker Ban law in North Carolina.

“Imagine I am a communist historian in 1966,” UNC’s university archivist Nick Graham told a group of about a dozen individuals on a cold, drizzly February afternoon during a tour highlighting student activism.

He continued with his reenactment, “I start to speak on campus. The campus police tell me that I’m not allowed to lecture under state law so here we go.” With that, he hopped the stone wall along Franklin Street separating the UNC campus from the Town of Chapel Hill. “Now I’m off campus.”

Lectures were then given from the sidewalk to a large group of students on McCorkle Place.

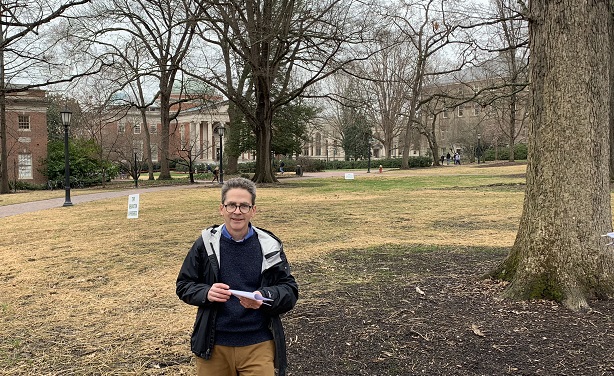

UNC archivist Nick Graham leading tour of history of student activism. Photo via Blake Hodge.

There is a marker on the stone wall commemorating that protest, a rarity, according to Graham.

“This is the only occasion of student activism that is memorialized.”

Graham said it was also a rare occurrence of the student body and university system administration working together to challenge state law.

From there, Graham led the tour to what he referred to as the turf renovation currently in progress on McCorkle Place – where the Confederate monument known as Silent Sam stood on the campus for more than 100 years. Graham said the area looked different than it had for any similar tour in the past.

“The first several times, there was a large Confederate monument here,” he said. “One time there was the base of a Confederate monument with no statue. Now this is the first time when we’re just standing in front of a turf renovation.”

The statue was not seen as controversial immediately after its installation in 1913.

“This was a campus of predominately men, all white students,” Graham said. “This would have been a memorial that would have been very familiar to them from courthouses, town squares, government offices all over the state.”

That changed over the years with the first documented opposition to the statue coming in an editorial in the Daily Tar Heel in the 1960s.

Graham said the statue was vandalized on multiple occasions over the years, from being covered in paint by rival fan bases before big athletics events to after the assassination of Martin Luther King Junior.

The conversations have evolved over the years to student groups beginning to strongly call for the statue’s removal in recent years. UNC history graduate student Maya Little poured a mixture of red paint and her own blood on the statue in late April 2018, which Graham said particularly stood out in the historical context of the statue.

“Of all the instances of student actions that we’ll talk about throughout the tour, Maya Little’s protest here was one of the only ones that I know of where an act of a single individual was that powerful and that effective in conveying a message and bringing attention to it.”

Protesters eventually toppled the statue in August 2018. The base of the monument was then removed in January.

From McCorkle Place, the tour wound through the campus to talk about the history of protests stemming from the Campus Y, including large events organized against the Vietnam War. Then it was over to South Building where shanties were once set up to protest apartheid.

One stop on the tour was in front of Manning Hall, which serves as an important location in the history of the Food Worker’s Strike at UNC 50 years ago.

Jennifer Coggins, who also works in the university’s archives, said the food worker’s strike was unique in the university’s history.

“This was a worker-led movement that found allies in student organizations on campus,” she said. “So, in this case, student activists were serving as allies to workers that were challenging the university.”

The strike took place from February 23 through March 21, 1969 and was met with opposition from the highest office in the state of North Carolina.

“The governor ordered that students be arrested if they disrupted campus services, he sent the highway patrol to ensure that the cafeteria could remain open and he put the National Guard on standby in Durham in case protests grew.”

Graham acknowledged there are many instances of student activism that couldn’t be covered in the hour-long tour. But he said these events help share the full history of the university.

“A big part of our job in the library and in the university archives is to encourage people to get excited about campus history and to learn about it,” he said. “And what we are especially interested in doing is to encourage people to get into the archives and explore on their own.”

An exhibit detailing the events of the food worker’s strike is on display at Wilson Library through late May.

A theatrical event bringing voices from the Food Worker’s Strike to life is scheduled to begin at 4:30 p.m. Wednesday at Wilson Library.