Additional restrictions should be placed on how absentee ballot request forms can be collected to discourage the type of illegal activity alleged in a North Carolina congressional race last fall, the state’s election chief said Wednesday.

State Board of Elections Executive Director Kim Strach made several recommendations to legislators, who would have to approve many of the changes that she discussed. Strach was the public face of the board’s investigation into absentee ballot irregularities that led the board last month to order a new election in the 9th District, essentially erasing the race’s November results.

The investigation showed the way outside groups can collect request forms from registered voters seeking traditional mail-in ballots can lead to abuses, Strach said.

“We want to make sure that voters are protected when they give forms to people in that process,” Strach told the House Elections and Ethics Law Committee.

Board investigators presented evidence in a February hearing that Strach said at the time showed a “coordinated, unlawful and substantially resourced absentee ballot scheme” during the 2018 general election in Bladen and Robeson counties, which is in all or part of the 9th District. According to testimony, the operation was led by McCrae Dowless, a political operative who had been hired to work for Republican candidate Mark Harris’ campaign.

Dowless and several workers were indicted two weeks ago on illegal ballot handling and other charges related to the 2016 general election and 2018 primary.

Dowless had testified in a 2016 board hearing that he paid his workers to collect absentee ballot request forms and turned them into the local elections board. Such activity is not unlawful. But testimony last month alleged Dowless paid people to visit voters who had received requested ballots and get them to hand the ballots over. It’s already illegal for anyone other than a guardian or close family member to handle a voter’s ballot.

Strach asked for legislation that would bar third-party groups from paying workers for each request form they collect, saying such per-form rates can provide an incentive for cash-strapped workers to fabricate requests using information from an unsuspecting voter. Absentee ballot collectors also should be required to turn in filled-out request forms in a timely manner and be penalized if they fail to deliver them to the local elections board office, she said.

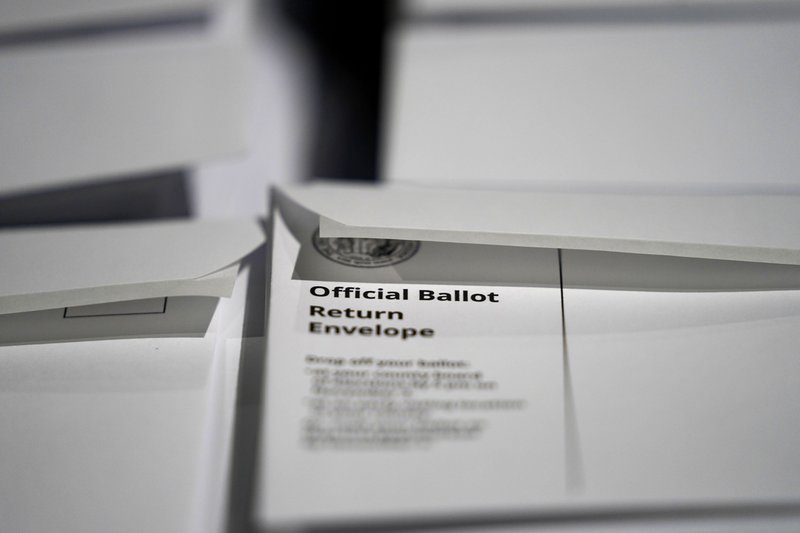

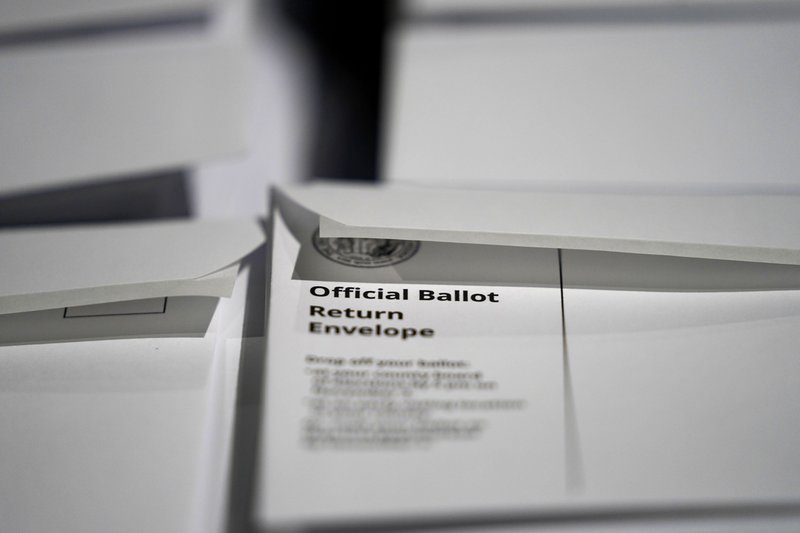

Illegal ballot “harvesting” — when an individual or group takes another person’s actual mail-in ballot — could be discouraged if a law requiring the voter to turn in the ballot at their own expense be eliminated, Strach said. Instead, ballot return envelopes could be affixed with prepaid postage, she said.

Strach said people in this electronic age are less likely to have the stamps needed to mail a completed ballot themselves — making it convenient to hand it over to the person coming to their door.

Strach also asked for additional state funds to increase the number of agency employees for elections investigation and administration. Strach said she’d like to see increased penalties for absentee-ballot law violations, which are now either punishable by a misdemeanor or lowest-grade felony. They usually don’t require time behind bars on a first offense.

“We need strong consequences for election interference,” she said.

Related Stories

‹

Several States Are Making Late Changes to Election Rules, Even as Voting Is Set To BeginNew or recently altered state laws are changing how Americans will vote, tally ballots, and administer and certify November’s election.

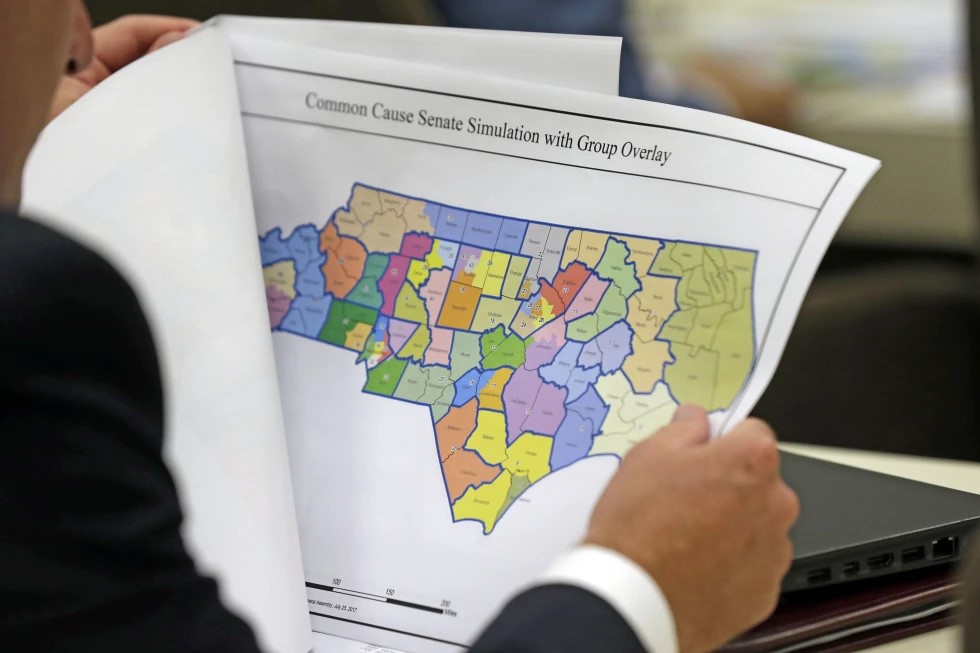

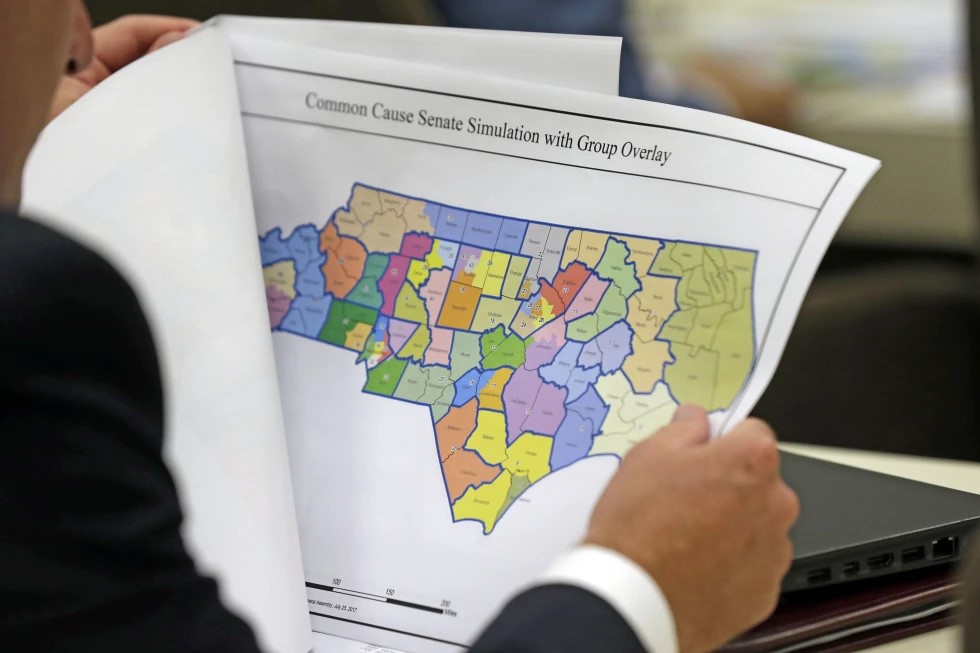

North Carolina Judges Grapple With Defining ‘Fair’ Elections in Redistricting SuitNorth Carolina judges are deciding whether a redistricting lawsuit claiming a state constitutional right to “fair" elections can go to trial.

NC Supreme Court To Hear Voter ID Arguments Next MonthWritten by GARY D. ROBERTSON Oral arguments over the constitutionality of North Carolina’s photo voter identification law will be held next month, the state Supreme Court has decided in another ruling determined along partisan lines. In a 4-3 decision, the justices who are registered as Democrats agreed with attorneys for minority voters who had asked the state’s […]

![]()

Democrats, Republicans Fight to a Redistricting StalemateWritten by NICHOLAS RICCARDI After nearly a year of partisan battles, number-crunching and lawsuits, the once-a-decade congressional redistricting cycle is ending in a draw. That leaves Republicans positioned to win control of the House of Representatives even if they come up just short of winning a majority of the national vote. That frustrates Democrats, who hoped to […]

NC Judges Deny Requests to Block Elections Under New MapsWritten by GARY D. ROBERTSON North Carolina’s 2022 elections under new legislative and congressional maps can begin as scheduled next week after state judges on Friday rejected demands from lawsuit filers who claim the lines have to be blocked because they so egregiously favor Republicans. The refusal of a three-judge panel to issue preliminary injunctions against the […]

Cooper Vetoes GOP Bill That Sought To Weaken AG’s PowersWritten by GARY D. ROBERTSON North Carolina Democratic Gov. Roy Cooper vetoed a measure Monday that would have limited the powers of the person in his former position — attorney general — to enter into future legal settlements. The legislation was passed by Republicans furious with Cooper’s successor over his handling of a 2020 elections lawsuit. […]

NC Appeals Court Stops for Now Voting Restoration for FelonsWritten by GARY D. ROBERTSON A North Carolina appeals court on Friday blocked an order that had allowed tens of thousands of felony offenders who aren’t serving prison or jail time to immediately register to vote and cast ballots. The state Court of Appeals agreed to halt last week’s decision by trial judges to expand […]

![]()

North Carolina GOP Senate Candidate Pat McCrory Raises $1.2MWritten by BRYAN ANDERSON Republican North Carolina U.S. Senate candidate Pat McCrory on Thursday announced he raised more than $1.2 million in his first fundraising period since he entered the primary in April. The former Charlotte mayor who lost a pair of general election gubernatorial bids in 2008 and 2016 but won in 2012 got […]

Absentee Ballot Turn-in Deadline Moved up in NC Senate BillAbsentee ballots in North Carolina would have to be received by county election officials by Election Day or the primary election date to be counted in legislation filed on Thursday by state Senate Republicans. The measure, which also would move up the usual deadline to request a mail-in ballot, comes as GOP lawmakers remain upset about […]

![]()

South Emerges as Flashpoint of Brewing Redistricting BattleWritten by NICHOLAS RICCARDI The partisan showdown over redistricting has hardly begun, but already both sides agree on one thing: It largely comes down to the South. The states from North Carolina to Texas are set to be premier battlegrounds for the once-a-decade fight over redrawing political boundaries. That’s thanks to a population boom, mostly one-party […]

›