What does it mean to be an American? That question has been debated and contested throughout U.S. history – and that debate is front and center again, particularly in the context of the Trump administration’s immigration crackdown and a recent speech by Vice President J.D. Vance at the Claremont Institute.

97.9 The Hill’s Aaron Keck recently welcomed two historians whose work addresses the question of American identity. Penn’s Rogers Smith is the author of “Civic Ideals,” a seminal 1998 work that identifies “multiple traditions” of American identity throughout U.S. history. UNC’s Lloyd Kramer is the author of the “Past Rhymes With Present Times” column on Chapelboro.com; his latest piece explores the competing traditions of “civic nationalism” and “ethnic nationalism” in America.

Click here to listen to their conversation. The transcript below has been lightly edited for clarity.

97.9 The Hill’s Aaron Keck with Lloyd Kramer in the studio. Rogers Smith joined the conversation on Zoom. (Photo by Aaron Keck/Chapel Hill Media Group.)

AARON KECK: Lloyd, your column talks about two grand overarching traditions of American identity. What should folks know about the history of that conversation as it’s taken place across American history?

LLOYD KRAMER: There are two competing conceptions of American identity. One is often called “civic nationalism” or “civic identity,” and it stresses that people become American because they affirm certain values about the equality of rights, about freedom (or) the Bill of Rights. And they are often opposed by people who say (that) to truly be an American means you come from a particular ethnic background (or) Christian religious background, (or) perhaps you’ve been part of American history for generations. That’s often called an “ethnic identity.” And there are ethnic components to civic identity, and civic components to ethnic identity. But the conflict between those two conceptions of American identity is a constant theme in American history.

KECK: Rogers, your work goes to the next level: you talk about three traditions of American identity.

ROGERS SMITH: Both the conceptions that Lloyd identifies are rooted in the fact that the United States was created by a coalition consisting primarily of propertied white Christian men. And they did create institutions that expressed the interests and values of those identities. But in the course of the revolutionary struggle, they (also) embraced the universal universalistic egalitarian ideals of the Enlightenment. They proclaimed that they were fighting a revolution to create governments that would secure the rights of all persons, and that would do so by the consent of the governed. And so they provided the groundwork for conceptions of American identity as devoted to principles of democracy and human rights. And ever since then, American political actors and movements have built support in very different (ways): some appeal to those principles of democracy and human rights, but some appeal to the identities and interests of that founding coalition.

KECK: Which has made it very complicated and very difficult, because as you mentioned, so many of these different conceptions of American identity can coexist and be talked about at the same time by the same people, oftentimes in the same sentence. But then they can go in many, many different directions, many of them contradictory.

SMITH: Absolutely. Barack Obama can say that in no other nation would his story even be possible, and appeal to the Declaration of Independence while presenting it as a special heritage and strength of the American people. So he’s got a certain blend of conceptions of American identity, embrac(ing) exceptionalism but (with) this universalistic element. And that can be a basis for building broad political support. But Donald Trump can come along and say “liberals are attacking traditionalist Americans (and) our Christian traditions,” and treating whites as victims. And that too can build a powerful coalition. Obviously, theirs are very clashing conceptions of American identity.

KECK: JD Vance just gave a speech at the Claremont Institute where he said: “America is not just an idea. We’re a particular place with a particular people and a particular set of beliefs and way of life.” How does that fit into the larger history of these discussions and debates about American identity? And where does that place people like JD Vance and Donald Trump in the larger context of American history?

KRAMER: JD Vance also noted that people needed to trace their lineage back to the Civil War or the American Revolution to be truly American. Which I found interesting – because the Civil War itself was in some ways a victory for the civic conception of national identity. The slaveholding South, and those who held slaves, said that Black people could never be fully American. They couldn’t even be citizens, by the Dred Scott decision. And in a way, the Civil War was another battle about identity: is it going to be limited to certain kinds of people, or does it include everyone? And that’s why the 14th Amendment, which came out of the Civil War, was fundamental to the affirmation of American birthright citizenship and identity not based on a particular heritage, but simply (by) being part of the community.

SMITH: Abraham Lincoln’s famous Gettysburg Address begins, “Four score and seven years ago, our forefathers brought forth upon this continent, a new nation conceived in liberty and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal.” Well, that ‘four score and seven years ago’ language is biblical language. And ‘our forefathers’ implies a kind of ancestral heritage. That is a rhetoric that invokes a particular culture and a particular people – but it is one that is said to be dedicated to a proposition that’s universal, that ‘all men are created equal.’ He goes on to say that the Civil War is testing whether this nation – which has a special commitment to that principle historically – ‘whether any nation so conceived can long endure.’ But note that while that’s a particular task for this nation, there is, again, the universalistic element: “testing whether any nation so conceived and so dedicated can long endure.” And Lincoln always emphasized that America should be a republican example to the world, of a system devoted to government “of the people, by the people, for the people,” securing the rights of all.

So he was a classic blend of America’s traditions. There was a recognition of a particular people and place – but as Lloyd just emphasized, that was an identity that was (also) understood to be dedicated to a broader project, ultimately a benefit to all humanity, of establishing government by the people that secured human rights. And incidentally, the Speaker of the House, Schuyler Colfax, said that Section One of the 14th Amendment (guaranteeing birthright citizenship) was the gem of the Constitution, because it embedded the Declaration of Independence, that understanding of American purposes, firmly in the Constitution, more so than ever in the past.

KECK: And so important to note that first line of Lincoln’s, right? He says “four score and seven years ago,” which we always gloss over – but that specifically refers back to 1776, the Declaration of Independence, (as) the foundation of everything. And that was very much a political statement – because you had people on the pro-slavery side who (were saying) the Declaration of Independence is not an expression of what American identity really is. Lincoln says we need to bring it to the front.

SMITH: Yes – he’s speaking in 1863, so he is clearly identifying by that number that America begins with the Declaration, and should understand itself as a political project of furthering the principles of the Declaration.

KRAMER: I think this emphasis on the Civil War reminds us that what we’re seeing right now is in some way a repetition of the debates of the 1850s and the 1860s. It’s therefore not coincidental that part of Trump’s campaign is to reestablish the legitimacy of Confederate monuments (and) Confederate heroes, because it is a Confederate narrative that said “some people are more American, some people are more deserving of rights than others.” And to reaffirm that tradition against Lincoln’s Gettysburg address is in some sense what’s happening, in the attack on birthright citizenship, in the attempt to deport immigrants, and in the resurrection of Confederate monuments.

KECK: And Lloyd, your column (also) talks about the early 20th century as well, as another moment in American history where this discussion rises to the forefront. (There are) moments where American history is characterized by one tradition, and then a different one rises in another generation. What’s caused that shift, in the past? For people who want to move the dial today, what lessons can we take from the past that can help us going forward?

SMITH: Unfortunately, one of the lessons of my work is that it takes extraordinary pressures to get America to move in a more egalitarian and inclusive direction. We’ve made progress toward greater racial equality only under conditions of war or war-like circumstances: during the Revolutionary War, (which led) to the first emancipation in the North, the Civil War, leading to the end of chattel slavery, and the Cold War, (which) helped precipitate conditions for the civil rights movement. At the current moment it does appear that the nation is on a much more conservative course, and it’s not likely to alter until most Americans feel that that course is taking them down to places that they don’t want to go.

KRAMER: I think what’s interesting is (that) there are these waves of reform. We could take the Civil War as an example: (it was) followed by Reconstruction, which provokes a reaction in the late 19th, early 20th century. You have the rise of the Ku Klux Klan again in the 1920s – but then the great upheavals like the Depression and the Second World War and the struggle against global fascism generated an awareness of the value of government and democracy, which gave rise to the civil rights movement and (the) huge reforms of the 1960s and 1970s. And what we are witnessing now is a kind of second reaction, like after the Civil War and Reconstruction. And I think the pressure, as Rogers has said, builds to a point that people say “this is not in tune with our American values.” That is to say, the reaction will be challenged, and (we) will move forward again. It’s hard to see at the moment how that will happen, (but) I will just say it will happen again.

SMITH: I certainly hope Lloyd is right about that, (but) I do not believe that there are iron laws of history. I think that it can happen, that we move into a new reform period, (but) it will happen only if the American people choose to make it happen.

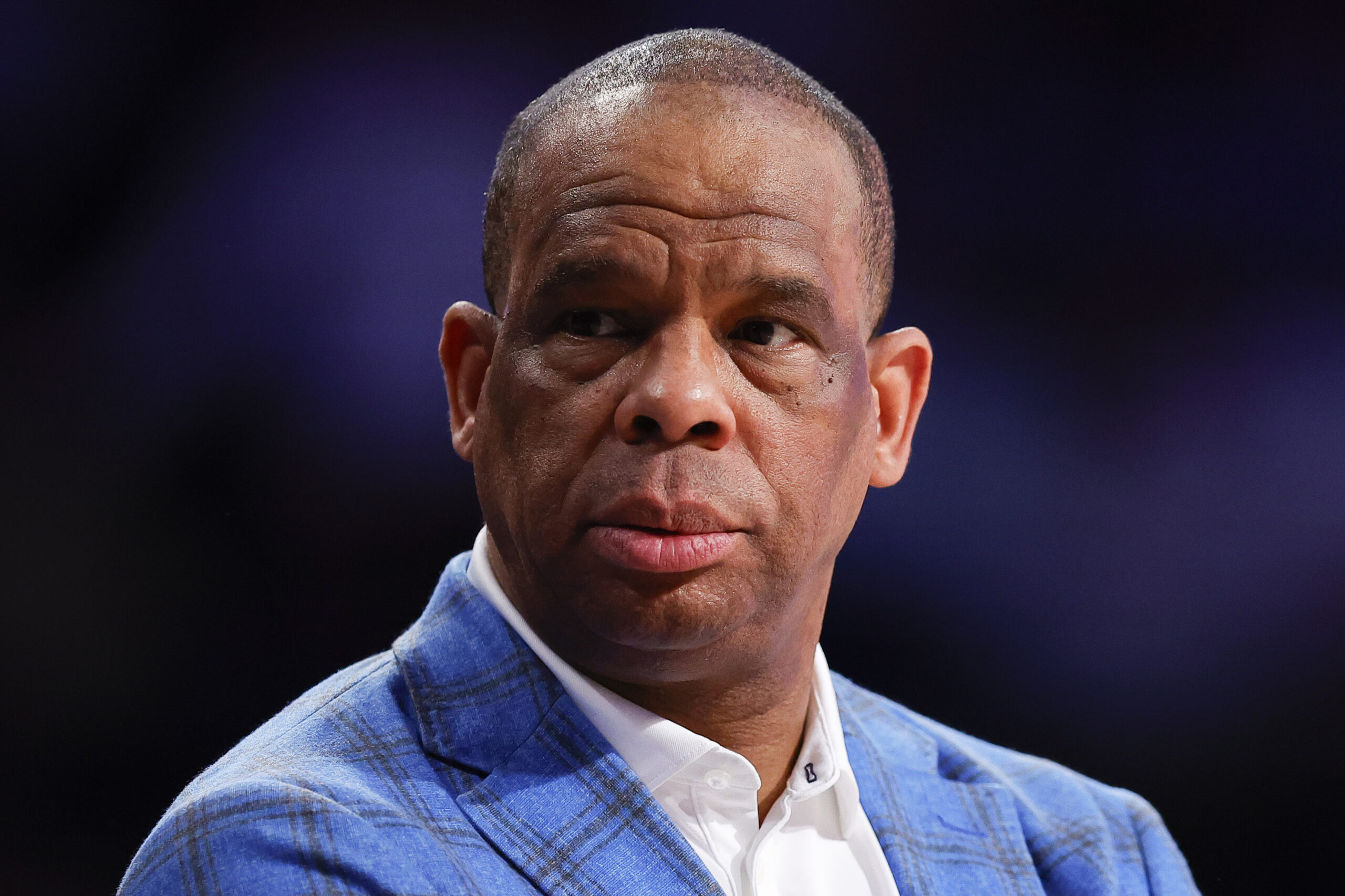

Featured photo via AP Photo/Evan Vucci.

Chapelboro.com does not charge subscription fees, and you can directly support our efforts in local journalism here. Want more of what you see on Chapelboro? Let us bring free local news and community information to you by signing up for our newsletter.