The 2010 midterm election was a sweep year for the Republican Party, with big GOP gains in state legislatures as well as Congress. The following year, after the 2010 census, those state legislatures – now GOP-controlled – got to redraw legislative district lines across the country. The maps they drew – using increasingly sophisticated precinct-level voting data – effectively guaranteed GOP super-majorities in state legislatures nationwide, even in evenly-split “purple” states like North Carolina.

And a new book by a UNC alum contends that this was a deliberate strategy from the beginning.

The book is called “Ratf**ked: The True Story Behind the Secret Plan to Steal America’s Democracy.” (The title refers to a Nixon-era term for dirty tricks.) Written by former Salon.com editor-in-chief David Daley, “Ratf**ked” describes how a small group of key players worked behind the scenes to redraw the nation’s district maps to lock in a GOP legislative majority. (It was called the Redistricting Majority Project, or REDMAP – and it wasn’t illegal, or even all that secret. REDMAP’s architect, Chris Jankowski, happily cooperated with Daley on the book, and Daley says they’re still collaborating on future projects.)

David Daley spoke with WCHL’s Aaron Keck.

Daley’s book explores how Jankowski and his cohorts identified and exploited a “loophole” in American democracy: the fact that state legislatures, in most states, get to draw their own district lines. Every ten years, following each new census, those district lines get redrawn – and whichever party controls the legislature can redraw the lines however it suits them. Winning a seat in the state legislature usually doesn’t cost much money – so Daley says the GOP was able to take control without spending much more than 30 million dollars. Once they did, GOP lawmakers in states like North Carolina used their redistricting power to cram as many Democrats as possible into a few districts – leaving all the rest safely in Republican hands.

A popular graphic explaining how gerrymandering can work.

The strategy is called “gerrymandering,” and it’s as old as the Constitution itself. The word “gerrymandering” was first coined 200 years ago, when Massachusetts lawmakers led by governor Elbridge Gerry drew a map with comically misshapen districts – including one that resembled a salamander. (Opponents called it a “Gerry-mander,” and the name stuck.)

The famous “Gerry-mander” editorial cartoon.

Gerrymandering has been common practice ever since – used by both parties to entrench themselves in power. But Daley’s book argues that there’s something new, and much more insidious, about the REDMAP project. Lawmakers today have much more sophisticated technology and data than they had in the past, Daley says – and that has enabled them to use gerrymandering more effectively than ever before. In the past, Daley says, there was always some guesswork involved in gerrymandering – but no longer. Lawmakers today can redraw districts in a way that virtually guarantees their party will remain in the majority – no matter which party gets the most votes in the next election.

Chris Jankowski. (Photo via Today.CofC.edu.)

The result, Daley says, is obvious: in North Carolina, and in states across the country, the GOP has maintained control – even though the actual vote has varied widely from one election to the next. 2012 was a big year for Democrats, 2014 was a big year for Republicans, and 2016 was fairly even – but in all three elections, the GOP’s majority in the General Assembly barely budged. Daley says that’s no accident: lawmakers drew the district lines (deliberately) so as to make the actual elections almost irrelevant. And new technology has made those efforts more effective than ever before.

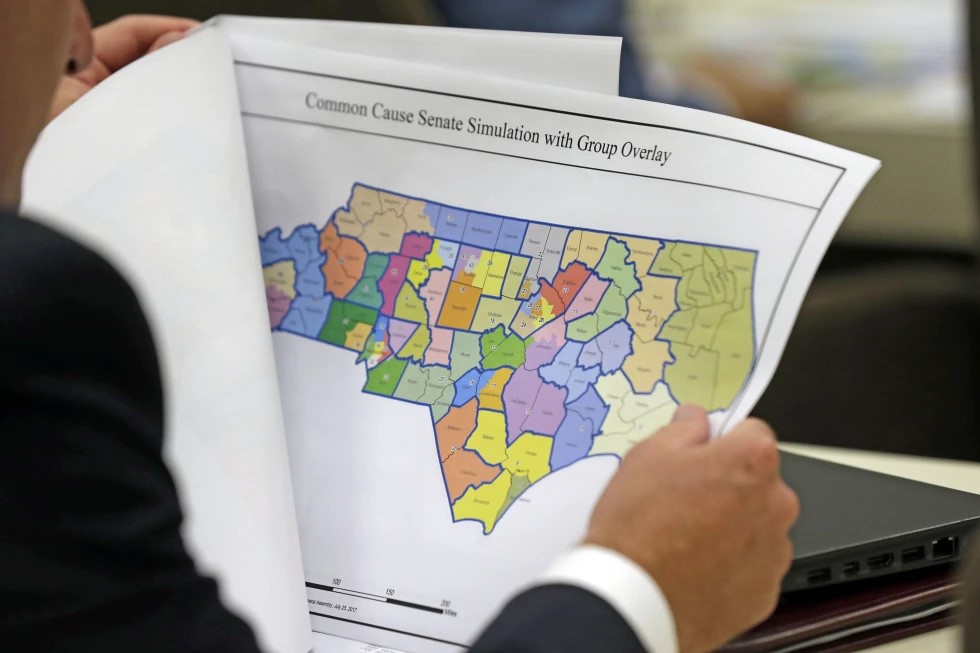

North Carolina’s US Congressional district map – with most Democrats crammed into districts 1, 4, and 12.

(It’s for this reason that UNC professor Andrew Reynolds recently argued – in an op-ed that went viral nationwide – that North Carolina barely even qualified as a democracy anymore. Elections don’t have an effect on government, he said, because our legislative districts are so heavily gerrymandered.)

What’s the future of gerrymandering? Several states have changed their redistricting policy, taking the power away from state legislators and giving it to independent nonpartisan redistricting commissions. (Advocates for fair government say it makes no sense for lawmakers to have the power in the first place: since they stand to benefit directly from a favorable district map, it only invites corruption. According to one popular slogan: “Voters should choose their representatives, not the other way around.”) In North Carolina there’s widespread support for an independent redistricting commission – from Democrats, Republicans, and independents alike – and lawmakers from both parties have introduced a bill in the NC General Assembly to create one. (A similar bill actually passed the House in 2011.) But the bill is not likely to pass anytime soon: State Senate leader Phil Berger has repeatedly insisted he won’t bring it to the floor for a vote.

If lawmakers won’t act, though, the Supreme Court might. The courts have long ruled that the Constitution forbids gerrymandering on racial grounds – drawing district lines to disenfranchise minority voters, in other words. Already this decade, numerous federal courts have ruled that North Carolina’s post-2010 district map was racially gerrymandered. Lawmakers last year had to scramble at the last minute to redraw the state’s 13 U.S. congressional districts after one such court ruling – and also last year, the Fourth U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals ordered the General Assembly to do the same thing for our state legislative districts too. (The Fourth Circuit ordered the state to redraw the districts and hold a special election in 2017 with the new map. Supreme Court justices issued a stay on that order for now, but they haven’t yet overruled the Fourth Circuit – or even decided whether to hear the state’s appeal.)

But Daley’s book contends that the REDMAP project was about partisan gerrymandering, not racial gerrymandering – and there, it’s not clear how the Supreme Court might come down. The Court has never ruled that partisan gerrymandering is unconstitutional, but some justices (Anthony Kennedy, most notably) have suggested that they’d be willing to do so if there were a clear formula for determining how much gerrymandering is too much.

And there, Daley says, REDMAP’s biggest advantage – its sophisticated technology – could also prove to be its downfall. The same technology that allowed Jankowski to perfect gerrymandering strategy is also being used by anti-gerrymandering advocates to develop a formula that justices can use to determine when a legislature has gone too far. Using that formula, the Southern Coalition for Social Justice has filed a lawsuit in North Carolina challenging district lines on partisan grounds – and there’s a similar case from Wisconsin, brought by the Fair Elections Project, that the Supreme Court may consider as early as this year.

How they will rule, Daley says, remains to be seen.

More information on Daley’s book here.