Every four years, the Orange County Health Department embarks on an intensive effort to gather wide-ranging, local health information in its Community Health Assessment, which happened in 2023. One month ago, the health department shared those results and data with residents.

The health department published its public copies of the 2023 assessment after surveys, focus groups, listening sessions, analysis of the health data and voting on the different priorities of the report. Its goal is to take a snapshot of the latest trends, socioeconomic factors and demographic data available in Orange County to examine the factors that contribute to health and dictate the community’s direction.

McKayla Creed, who is the Healthy Carolinians of Orange County coordinator and took part in studying and publishing this latest assessment, spoke with 97.9 The Hill’s Aaron Keck about the report. Below is a transcript of Creed and Keck’s conversation, which has been lightly edited for clarity. Click here to listen to their full interview, and read the full 2023 Community Health Assessment here.

Aaron Keck: So, before we get into the details, what all goes into this document and putting it all together in the first place?

McKayla Creed: It is quite a lengthy process. Most of it started before I even came to Orange County. I’ve been here for about six months now. In total, it’s about a 14-month process — lots of data collection. We go door to door, do surveys, secondary surveys, tertiary surveys. We take data from the county, from the state birth and death certificates. So, it’s pretty much six months of writing this huge document, looking at every single data point that we can think of that’s gonna affect our community. That’s going to be housing, health, education income… literally every statistic you can think of.

Keck: This report is 156 pages long, so we’re not going to cover every detail — please share an elevator speech summary. What did you find? What should folks take away?

Creed: So, we came out with three basic priorities, and they’re very important priorities. Our first one is behavioral health, and that focuses just on mental health, suicide, and substance use. For those who aren’t in public health, suicide is actually in the top ten leading cause of deaths for Orange County. And that’s not even in the top ten for the state. So, clearly that is an issue specific to us. We had about half of the people that completed our survey say that someone in their house has anxiety, has depression, has both, and they’re not aware where to go to get these mental health services. That’s something we really wanna touch on.

Our second is access to care, and that’s a huge focus on insurance, Medicaid, Medicare providers, and infant mortality rate. We do have quite an unfortunate discrepancy with African American infant mortality and white infant mortality in Orange County. Again, that is something we do see at the state level, but the discrepancy level is unique to Orange County.

And then our third priority is connections to community support. This is all about social determinants of health: your healthy foods, your exercise, your transportation, your housing, your childhood experiences. Orange County is very unique in that we have a great community — lots of sidewalks, lots of parks, lots of people that want to be fit and want to be active. But a lot of people don’t know exactly how to access those things, like where we have community gardens which are free sources for free, locally-grown produce. Part of that priority is just getting people connected to those things. We do have about a fifth of Orange County [residents] ages 18 to 64 living in poverty, and that is due to the fact the cost of living is just so insane right now.

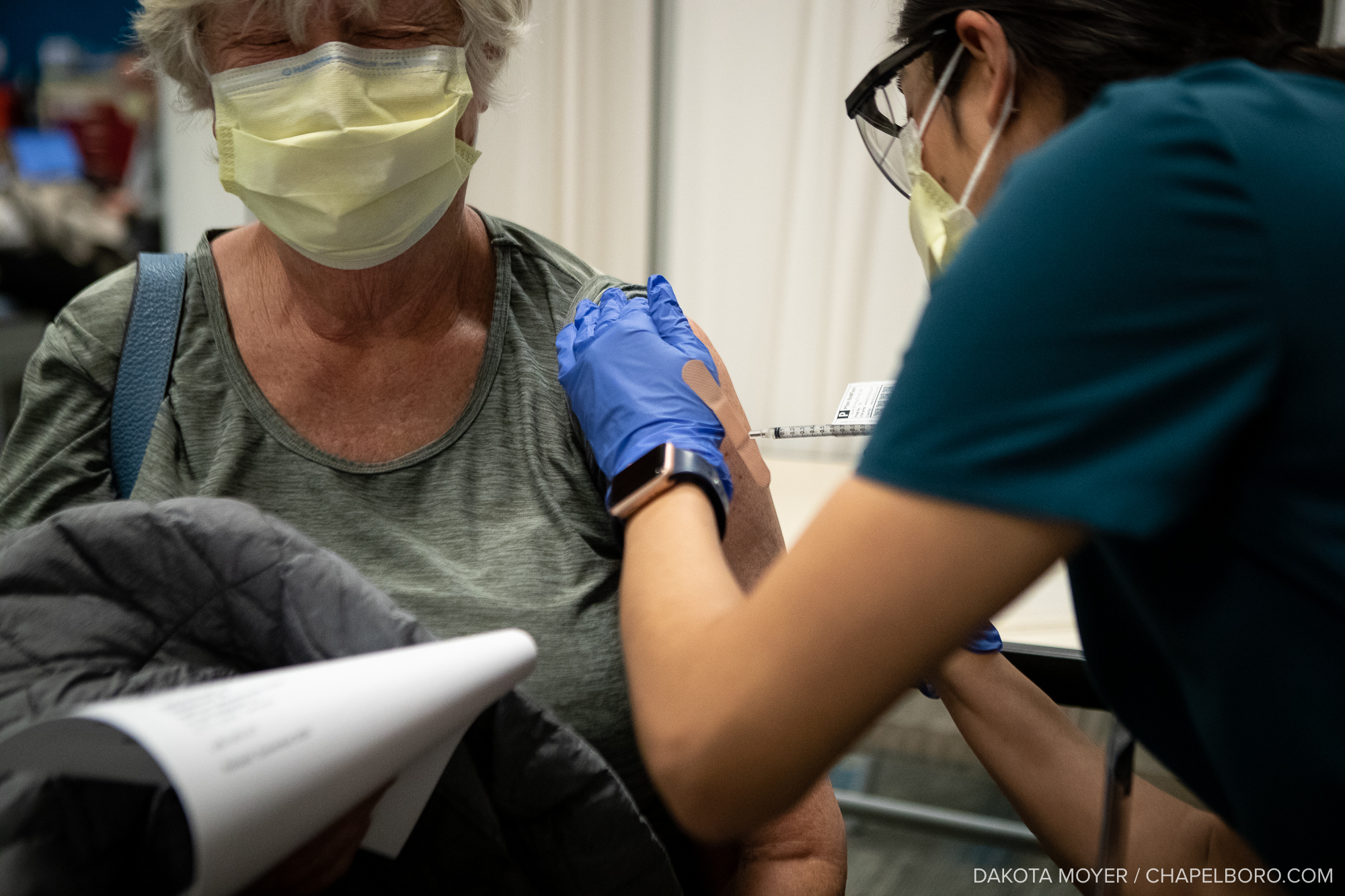

McKayla Creed (right) of the Orange County Health Department speaks with 97.9 The Hill’s Aaron Keck.

Keck: What do we know about the way that all three of those things are trending? Because I’m sure all three of those things would’ve been issues four years ago. How are they today versus then? Are things better or worse?

Creed: They are… both. Typically, compared to all of our peers into the state, Orange County does very well when it comes to actually getting our people to the care that they need. We have UNC, we have Duke, we have a plethora of providers, and that is so great for us. Unfortunately, COVID really hurt us — and the isolation, people’s mental health, suicide rates, all of that has increased since COVID. That’s awful. I can’t tell you what it would’ve been like if COVID never happened. I can only imagine it would’ve increased as well, but I’m not sure it would’ve increased to that level. And then of course, the cost of living. I heard something on the news the other night, our gas might get to $5 a gallon by the end of the summer. How are you supposed to do that, and go to work, and feed your kids, and do daycare in the summer because kids aren’t in school? Everything is just, unfortunately, getting worse in terms of people needing help.

Keck: And with COVID, that’s in spite of the fact that Orange County, relatively speaking, did fairly well. Our COVID metrics were way below the state average in terms of number of cases, cases per capita, deaths per capita. We did a really good job handling the pandemic compared to to other counties around us, and still the impact was really huge.

You mentioned the infant mortality rate for African Americans. That was one of the more significant things that jumped out to me because, as you mentioned, Orange County’s health metrics tend to be significantly better than other counties around North Carolina. That was the odd outlier, that the infant mortality rate among African Americans is actually quite a bit higher than the state average. What do we know about that?

Creed: Yeah, just for rough estimates in Orange County, infant mortality rate for African Americans is about six times higher than our infant mortality for whites. And that’s with the same healthcare systems. We do look at birth and death certificates just for Orange County, so there’s no outside influence of people coming from Durham, Alamance, anything like that. And I do want to give one shout-out to Dr. Alison Stuebe, who serves on our board of health, and Quintana Stewart, who’s our health director. They recently received a grant that they’re going to work on for the next six years, to specifically reduce incidents of hypertensive disorders in pregnancy and improve maternal outcomes in North Carolina. They’re doing it with Orange County and nine other counties, and it’s about a $20 million grant.

Part of maternal health and infant mortality rates that you really have to understand, you have to be healthy pre-pregnancy to have a healthy pregnancy and a healthy postpartum pregnancy. And, unfortunately, women in general have a higher allostatic load, which is the wear and tear on your body — any of the stress that you get as a child, going through puberty, natural things like that. And then you take in the fact that you’re an African American woman, you’re exposed to systemic racism, racism out in neighborhoods, things like that. And we did have people report that they do experience racism in Orange County — unfortunately that is not unique to us. But, an interesting part of that is that we can kind of correlate our African American infant mortality rate specifically to that systemic racism. When you look at black immigrants from the Caribbean [countries] or from Africa, when they come in as adults and have their pregnancies here, their infant mortality rates are significantly lower along with their low birth weights and premature births than native born African Americans.

The Human Genome Project legitimately said that we are 99.9% identical across races. So, it’s clearly not because of the race that they’re having this issue. It’s something internal, systematically. And one thing I do want to point on is that a lot of the people who took our survey, they openly admitted that whether they were African American, Hispanic, Asian… mental health is still stigmatized a lot. Thankfully, we’re getting kind of past that barrier. But [for] African American women in general, about 70% of them said mental health care during and after pregnancy wasn’t something they were provided. So, when you have women that are already at a disadvantage because of their sex, and because of their race, and they’re stressed out, and they aren’t getting the same amount of care or any of those things… they don’t have appropriate housing, the appropriate workforce, appropriate nutrition… you can’t expect them to have healthy pregnancies and healthy post-pregnancies. A huge thing with that issue is getting in with these women pre-pregnancy and during their pregnancy, and making sure they are healthy at that point so they can have their healthy labors.

Keck: I presume all of those issues are issues outside of Orange County as well, but the infant mortality rate for African Americans is higher in Orange County than it is elsewhere. So, are there any of those issues that are more significant in Orange County versus, say, Alamance County or Ashe County or any other place in North Carolina?

Creed: Yeah, so it was actually kind of odd to us. We triple, quadruple-checked our data. Other than infant mortality, the only thing that Orange County “does worse” than all of our peer counties in the state is breast cancer incidents, which is also shocking. A lot of people said ‘maybe it’s because you screen better’ … but that doesn’t necessarily lead to higher incidents. And we did have a woman during one of our listening sessions, she stated (that) on the street that she lives — I’m not going to give names or specific identities or anything like that — but she has so many women on that street with breast cancer, and she and the two women that owned the same house before her also had breast cancer.

So, clearly that is a more environmental thing. And, unfortunately, these women were African American and we do have the historic segregation lines, and we still are kind of segregated in that way. It’s not [solely] that they’re African American, or breast cancer incidence rate is high, or infant mortality is high. It’s because they are literally living in a space where they’re exposed to things that not everyone else is exposed to.

Keck: Speaking of meeting with community members about this data, there are some upcoming meetings happening later on this month, right?

Creed: We have one on May 14 around 2:00 PM in the Chapel Hill Public Library. And then we have one on May 16 at about 10:30 a.m. in the Orange County Public Library [in Hillsborough]. So, what we do with these is the community health improvement plans. We’re taking all the data, all of our priorities from the actual community health assessment and we’re saying, ‘Okay, here is the data. You’re our community partners, you’re our residents. The next four years of our health priorities and health education is gonna be based on this. What do you want to do? What do you expect to see? What actual measures do you want to hold us accountable for?’ That is open to our community partners, faith leaders… anyone from the community that has any sort of interest in this. We are welcome to all.

The full Community Health Assessment, as well as other studies conducted by the Orange County Health Department, can be found on the county government’s website.

Featured photo via cottonbro studio.

Chapelboro.com does not charge subscription fees, and you can directly support our efforts in local journalism here. Want more of what you see on Chapelboro? Let us bring free local news and community information to you by signing up for our newsletter.