UNC’s Institute for Global Health and Infectious Diseases researchers have begun phase 2 and phase 3 evaluations of promising treatments for COVID-19. The UNC School of Medicine joins more than 25 initial sites participating in these clinical trials sponsored by the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

ACTIV-2, is a NIH-sponsored partnership that is coordinating the research and development of COVID-19 treatments and vaccines. This two-phase trial is being conducted by the AIDS Clinical Trials Group to evaluate the safety and efficacy of treatments for adults who have COVID-19 but do not require hospitalization.

Throughout the randomized, controlled study, investigators will continue to identify new treatments to test against placebos. To qualify for the study, participants must have tested COVID-positive within the last seven days and started experiencing symptoms within 10 days of enrolling.

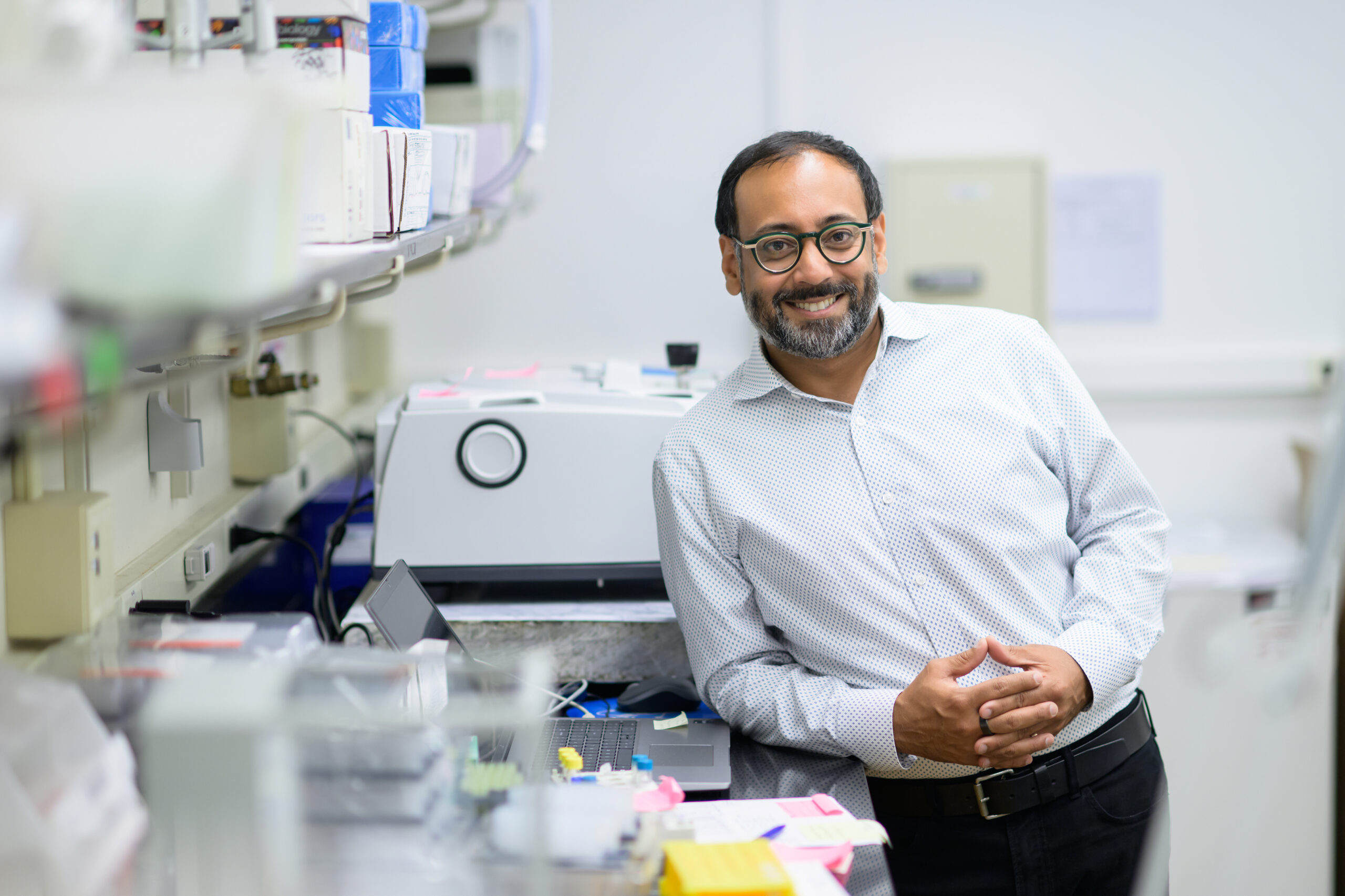

Dr. David Wohl is the principal investigator of the study at UNC. He also co-leads the respiratory diagnostic center at UNC Medical Center and oversees the testing and treatment of hospitalized patients. He said his team is casting a wide net to discover which therapies generate the best results.

The first agent to be evaluated by ACTIV-2 is an experimental monoclonal antibody treatment made by Lilly Research Laboratories in Indiana. An antibody is a protein of the immune system that circulates in the blood, recognizes foreign substances like bacteria and viruses, and neutralizes them. After exposure to a foreign substance, called an antigen, antibodies continue to circulate in the blood, providing protection against future exposure.

Monoclonal antibodies are laboratory-produced molecules engineered to serve as substitute antibodies that can restore, enhance or mimic the immune system. In this case, the monoclonal is a lab-made clone of an antibody found in the plasma of one of the first people in the U.S. to recover from COVID-19.

“This is an antibody that was identified in a survivor of COVID-19 that neutralized the virus really effectively,” Wohl said. “So what we’re doing is mimicking a natural, organic response that an individual human has made, and that was effective, and replicating it.”

Wohl said the phase 2 evaluation of treatments involves determining the safety, antiviral activity, and ability of tested agents to reduce the duration of COVID-19 symptoms over 28 days. He said half of the 220 study participants will receive the monoclonal antibody treatment while the other half receives a placebo.

“So when people enter the study right now they are randomized to this monoclonal versus placebo,” Wohl said. “For the first 220 people, we’re collecting data on basic efficacy – does it reduce symptoms – does it reduce viral shedding from the nose – those are the types of things we care about along with safety. If that looks good, after 220 people, we will graduate to a larger phase 3 study in which 2,000 people will be enrolled.”

Wohl said the larger phase 3 study will be looking to reach the ultimate goal – finding a treatment that prevents people from being hospitalized or dying. One of the best ways to do that is to focus on prevention.

Monoclonal antibodies provide an alternative avenue for the prevention of COVID-19. Wohl said a one-time, intravenous infusion could serve as a preventative treatment pre or post-exposure to the virus, offering immediate protection that could last weeks or months.

“When we give plasma, we’re giving a whole host of antibodies to people, and you’re hoping that in that plasma there’s at least one or maybe a family of antibodies that can work to neutralize the virus – meaning not allow it to enter into cells and cause damage,” Wohl said.

While this study sounds promising, Wohl said they still don’t know if having these specific antibodies will actually be protective for patients going forward.

“So we need enough time to look for people to get infected if they’re going to get infected,” Wohl said. “Remember, the vaccine studies are placebo controlled – half the folks are not getting a vaccine and the other half is getting a vaccine – and we need to see if there are rates of infection that are different. That’s why we’re enrolling people who have some risk of infection. People like Uber drivers and people who work in places like correctional settings and nursing homes.”

Wohl said it takes a lot of work for scientists to get a research study off the ground – especially when the virus was virtually unknown until 6 months ago. Because of this, it will take time to garner all the data needed for an initial treatment and then adjacent vaccine. Even then, Wohl said the creation of a vaccine is not guaranteed.

“So I think we should be careful about external timetables,” Wohl said. “I think we should let the science do what it needs to do, do it as rapidly as possible – where we don’t have the luxury of time – but this is a process that usually takes months not weeks.”

For more information on UNC’s clinical COVID-19 trials, and to find out where you can get involved, click here.

Chapelboro.com does not charge subscription fees. You can support local journalism and our mission to serve the community. Contribute today – every single dollar matters.