In order for COVID-19 tests and vaccines to be effective, researchers need to understand both the genetic makeup of the virus and to what extent it has mutated since first discovery. To do this, scientists can look at the virus’s genome, or complete set of genes or genetic material, to see if current testing and treatment needs to be adapted.

Dr. Dirk Dittmer, a professor of microbiology and immunology at UNC’s School of Medicine, is tracking the coronavirus by sequencing the genome of virus samples collected from UNC’s COVID-19 testing. With a grant from the N.C. Policy Collaboratory, Dittmer’s lab uses Next Generation Sequencing to accurately diagnose the novel coronavirus, identify mutations and track its history.

Dittmer said Next Generation Sequencing is vital because much of the testing developed to diagnose COVID-19 looks for a single portion of the gene sequence. If that sequence mutates, the test is no longer accurate and results will be affected.

“When we’re testing for the virus, we use a different technology that looks at a tiny bit of the virus called polymerase chain reaction and we need to make sure that that tiny region of the virus doesn’t change – because if it changes then the tests wouldn’t work,” Dittmer said.

COVID-19 testing isn’t the only thing affected by the mutation of the virus. Back in March, a change on the coronavirus’s spike protein forced scientists around the world to adapt their vaccine design.

“The spike protein is not just any protein,” Dittmer said. “It’s the one protein that the virus uses to enter cells and it’s the one protein that all the vaccines are made against. So that was important news because we and others could tell the vaccine manufacturers that they needed to not make the vaccine against the first strain that was isolated in Wuhan, but against the strain that had this new mutation that emerged in Europe and in Italy – and they did that and since then there haven’t been many more changes.”

While the spike protein on the coronavirus did mutate once, Dittmer said it’s very rare. This is why both the CDC and UNC’s Medical Center specifically designed their COVID tests to target the spike protein – to create a more stable, universal test.

Again, by looking at a virus’s genomic sequencing, scientists can determine where the virus was introduced from – whether it be from another state or out of the country – and how it has mutated since introduction. Dittmer said these understandings are crucial as a universal vaccine continues to be developed.

Because there have been so few changes to the coronavirus’s genetic makeup, Dittmer said the vaccine that was designed back in March will still be effective in January or February when it becomes available.

“This is where the SARS coronavirus or even the common cold is different than the flu shot,” Dittmer said. “The flu shot changes dramatically and that’s why you get a different one every year. This one doesn’t change much.”

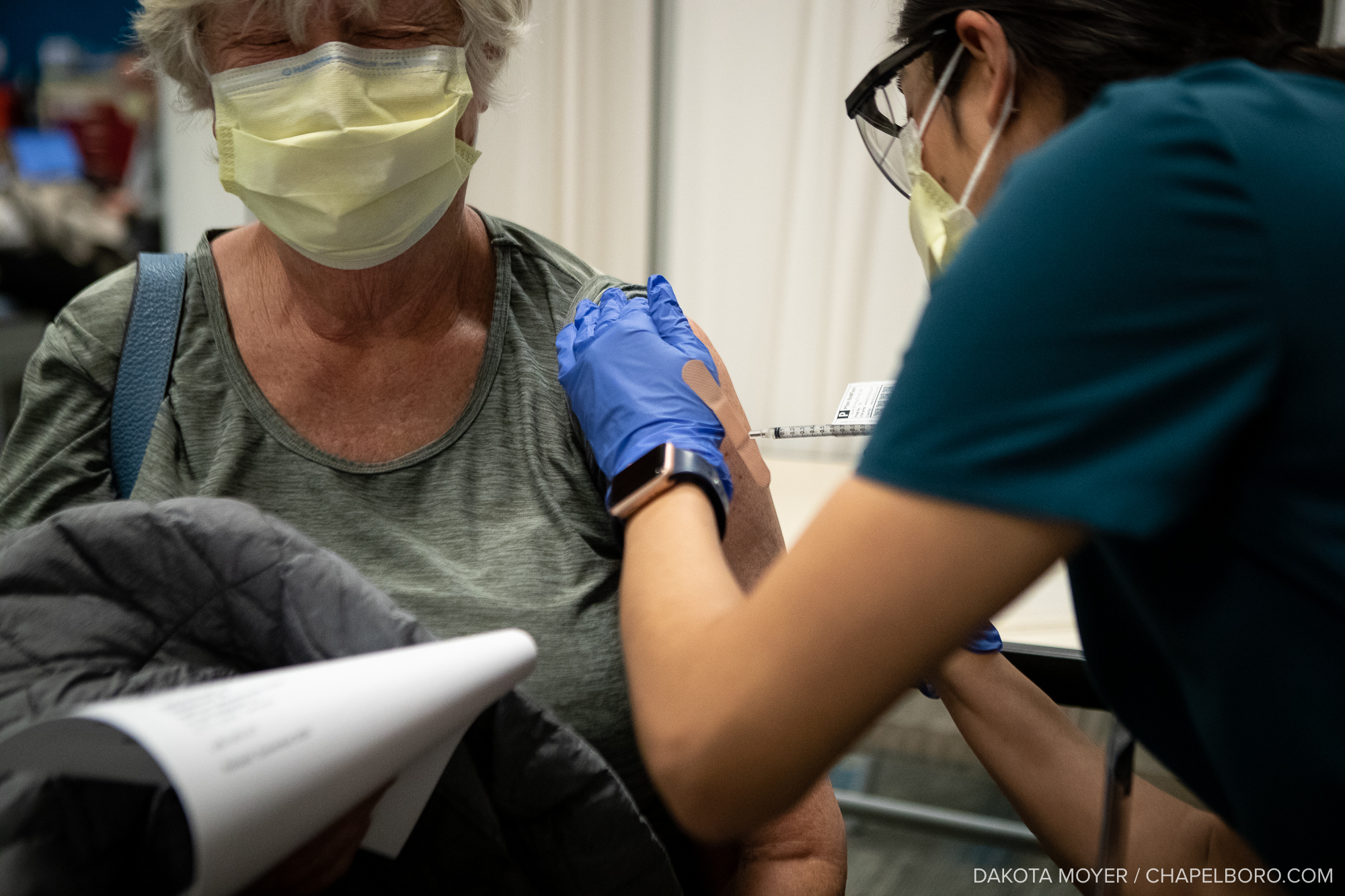

When a vaccine does become available, Dittmer said only 30 percent of the population needs to be vaccinated to effectively stop the spread of COVID-19.

“The good news is that we don’t have to vaccinate every single last person in the U.S., but just enough to come within that statistical range – which again makes me hopeful that once they have a vaccine it’s actually going to be fairly quick to get us back to normal,” Dittmer said. “Not everyone has to be vaccinated for the virus to be eradicated. That’s what herd immunity means.”

He said the reason so many vaccines are currently being created and tested is so medical professionals can select the best fit for each person. Much like how there are two flu vaccines this season – with one specialized for the elderly population – Dittmer estimates there will be five COVID-19 vaccines.

“So there will be vaccines that are better for elderly patients, there are vaccines that are super safe but you might have to take three shots instead of one shot – and so the more we have the more your physician will be able to advise you which one to take,” Dittmer said.

Read Dr. Dittmer’s latest study detailing how he and his team are using Next Generation Sequencing on samples of the SARS-CoV-2 virus to track its movement in the state here.

Lead photo via AP/Ted S. Warren.

Chapelboro.com does not charge subscription fees. You can support local journalism and our mission to serve the community. Contribute today – every single dollar matters.