“Viewpoints” is a place on Chapelboro where local people are encouraged to share their unique perspectives on issues affecting our community. If you’d like to contribute a column on an issue you’re concerned about, interesting happenings around town, reflections on local life — or anything else — send a submission to viewpoints@wchl.com.

FSU’s Amended Complaint: No Tomahawk Chalk, and Skepticism Towards the Swofford-Raycom Conspiracy Is Justified

A perspective from David McKenzie

FSU Does Little to Enhance Its Legal Position Against the ACC in Its Amendment. The Allegations about Swofford, Raycom, and Swofford’s Son Are Speculative at Best.

David McKenzie is an attorney in the Raleigh-Durham-Chapel Hill area. He specializes in intellectual property law and can be reached at david@mckenzielaw.net

Florida State University’s amended complaint is just as unimpressive as its first. Despite FSU’s efforts to depict mismanagement and self-dealing by way of a North Carolina-based conspiracy, its case remains weak. This article, designed again for accessibility, discusses FSU’s amendment. Overall, the core issues of FSU’s dispute remain unchanged, as do my conclusions regarding FSU’s first complaint.

Copyright and Contract Law Still Prevail

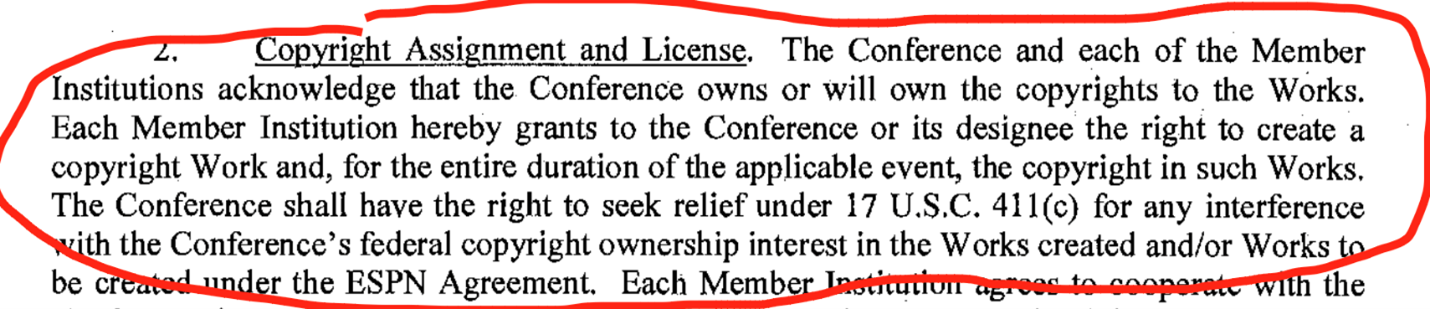

My initial analysis highlighted FSU’s voluntary acceptance of the Grant of Rights (GOR) and the binding power of copyright and contract law. While FSU’s amended complaint adds inflammatory accusations, the core issues are unchanged, and my original conclusions remain: copyright and contract obligations, not changing market conditions or regrets, control. FSU continues to face an uphill struggle, especially given its voluntary acceptance of the GOR and its lack of meaningful contract defenses. You can review my original analysis here.

There Was No Fraud, and FSU Essentially Alleges Fraud Without Actually Asserting It as a Claim. FSU Doesn’t Because It Can’t.

This is Litigation 101: alleging a claim or defense of fraud is serious business, and the rules governing complaints require that it be done with “particularity.” In its amended complaint, FSU says, more or less, that Swofford duped FSU into signing the GORs.

As for the 2013 GOR, FSU’s allegations heavily rely on an unverified and anonymous blog post from 2013 titled, “The ACC Defrauded FSU of Its Media Rights,” published on Big 12 Insider. This post included a link to a “Competitive Market Analysis” (CMA) authored by an unknown person and provided to FSU by another unknown person within the ACC. (FSU does not claim its own employees provided the CMA to its lawyers; one can only assume, again, that it originated from an online source.)

FSU contends the CMA demonstrates fraud, but the actual CMA lacks any financial forecasts, predictions, or promises. Instead, it is heavily laden with graphics and lacks substantive detail expected in a “market analysis,” competitive or otherwise. It is, at best, a PowerPoint presentation conveying broad generalities about the potential of sports broadcasting across the ACC’s expansive geographic market compared to other conferences. In the context of “particularity,” FSU’s use of the CMA and blog post to support its allegation of fraud is, at a minimum, reaching. A link to the CMA is found here.

As for the 2016 GOR, FSU alleges that the ACC literally “coerced,” “trapped,” and ultimately deceived FSU into signing the GOR. FSU essentially claims that the ACC falsely linked the 2016 GOR to securing a better ESPN deal and an SEC-like network. FSU alleges the ACC misled members about the 2016 GOR’s true purpose: simply “barricading” or locking in member schools in without additional revenue. (The additional revenue part is highly debatable.) However, outside of FSU just saying there was coercion and trapping, FSU offers literally nothing more— not even second undated and unattributed “Competitive Market Analysis.”

If FSU wants to dance with the extremely serious concept of fraud in a court of law, then it absolutely must come to its gunfight with an actual gun. This means providing specific facts, not just broad generalizations or subjective interpretations. FSU’s accounts around the signing of the GORs lack details of any kind, including but not limited to the specific actions taken by Swofford, or how his actions constituted “coercion.”

The Sophistication of FSU Officials Suggest Fraud Was Unlikely

Yet, critical to FSU’s veiled fraud allegations is to understand the caliber of individuals operating on FSU’s behalf in 2013 and 2016. It’s paramount to recognize that these were not novices.

Eric Barron and John Thrasher, presidents of FSU during the respective signings of the GORs, brought to the table a formidable blend of academic, legal, and political expertise. Barron, with a Ph.D. and a notable scientific career, and Thrasher, not just a seasoned lawyer but also a veteran in business and politics, embodied the epitome of informed leadership.

Moreover, FSU’s Athletic Directors at the time, including Stan Wilcox – a lawyer with extensive experience in Duke’s athletic department – alongside an FSU Board of Trustees overflowing with educated and affluent members, further underscore the intellectual and strategic might FSU had at its disposal. The assertion that such a cohort of experienced and sophisticated individuals could be easily misled or defrauded strains credulity to its breaking point.

FSU’s Sourcing of Its Faces Is Deeply Flawed. FSU Avoids Using Firsthand Knowledge or Inside Information

FSU’s entire amended complaint hinges mostly on online articles and blog posts. A whopping 18 such sources, cited at least 55 times, underpin the entirety of FSU’s claims, including the mismanagement and conspiracy belonging to Swofford, Raycom, and Swofford’s son. FSU’s heavy reliance on these sources, absent any firsthand knowledge, raise questions about the narrative’s believability.

The resulting story is replete with conjecture, speculation, innuendo, and accusations devoid of inside information. FSU’s dependence on external interpretations, rather than concrete internal evidence from its own people, flatly weakens the believability of its allegations, especially in a legal proceeding that demands proof. This approach becomes particularly problematic when FSU ventures into alleging fraudulent misconduct by Swofford and the ACC.

Ditch the Conspiracy Theory: FSU’s Shaky Evidence Undermines Raycom-Swofford Allegations

FSU’s amended complaint raises allegations concerning former ACC Commissioner John Swofford, Raycom, and Swofford’s son, claiming collusion related to financial benefits for Raycom and securing the younger Swofford’s ongoing employment.

However, look closely and you will see that FSU’s Swofford-Raycom allegations are based largely on a single, 14-year-old article from the Washington Business Journal, which raises concerns about any evidence FSU actually has. The absence of firsthand accounts from Tallahassee, including details like meeting minutes, emails, or internal documents, further fuels questions about whether FSU has any actual evidence to support its Raycom-Swofford conspiracy.

Otherwise, FSU’s oblique targeting of Swofford’s son and its attempts to associate him with its woes are especially dubious. A father doing a son a solid is not unusual – anyone remember Bobby Bowden hiring his son, Jeff, as offensive coordinator? – and FSU has not clearly shown that Swofford did so. Even if Swofford did save his son’s job, FSU has not demonstrated how that harmed FSU. (As discussed below, the timing of it all makes it nearly impossible.)

At any rate, the allegations concerning Swofford’s son are again questionably sourced. I am not a Swofford apologist, but if FSU is going to target not only a nonparty but a nonparty’s son, it should have the strongest of grounds.

Sourcing aside, FSU presents no clarity that the Raycom deal was bad for FSU or the ACC, and the use of tiers was certainly not unusual.

First, Raycom did not enter into a deal directly with the ACC. Rather, the ACC negotiated a deal with ESPN for its entire media rights/catalog, and as part of that ACC-ESPN deal, ESPN then entered into a sub-licensing agreement with Raycom for lower-tiered rights. This reality has been lost on some.

FSU claims the 2010 ESPN-Raycom deal caused significant financial losses and decreased ACC and FSU value because of the tier system Swofford engineered for Raycom. However, FSU does not explain how this harmed it, and FSU overlooks the fact that tiered licensing is a common practice within the industry.

Licensing in Tiers is the Norm

Here, allow me to demonstrate that, absent something genuinely spectacular, the Raycom deal was not abnormal.

Copyright licensing (and sublicensing) in tiers happens all the time and is industry standard. This is how Duke-UNC basketball (Tier 1) is shown on ESPN on a Saturday at 7 PM while Louisville-Pitt (Tier 3 or 4) is relegated to the lowly CW Network on the same day at 12 PM. (In another era, the first Duke-UNC game occurred on a Wednesday, but it was still Tier 1.)

Similarly, the NBA has broadcast partners like ESPN/ABC and TNT that air Tier 1-2 games (Lakers-Heat). It also has regional sports networks (like NESN or MASN) that hold rights to broadcast local teams’ games (Hornets-Pistons), which are generally less significant (Tier 3-4). The key point is that tiered licensing is not new and is standard practice.

Tier 1 Football Broadcast Rights

In its amendment, FSU emphasizes 80% of league revenues come from Tier 1 football broadcast rights, which Raycom never had. Though FSU pleads that Raycom had Tier 2 rights, the reality is that, according to FSU’s own online sourcing and plain observation, Raycom had at best Tier 3 (and most probably Tier 4) rights. Raycom’s deal likely constitutes only a fraction of the remaining 20%, given its lower-tier focus.

Essentially, FSU’s argument contradicts itself by acknowledging the value of Tier 1 rights while failing to demonstrate harm from the lower-tier Raycom deal. Instead, it simply says so, and then FSU does not revisit the 2010 ESPN-Raycom deal throughout the rest of its amended complaint.

At a minimum, the ESPN-Raycom deal was not an anomaly, and FSU’s accusations lack the critical element of demonstrable harm within the context of tiered licensing. Until FSU addresses this key point, I can’t figure out how the 2010 ESPN-Raycom deal has the significance FSU claims it has.

FSU’s Role and Consent in the Raycom Agreement

FSU’s account suggests its own complicity, either through formal endorsement or lack of challenge. FSU does not plead that it objected to the Raycom deal in 2010 or before. That, coupled with a 15-year silence until grievances were aired in 2023, points towards FSU’s implied approval. This extended period of non-action undercuts FSU’s current dissatisfaction and casts doubt on the legitimacy of its retrospective discontent.

Otherwise, the Timing of FSU’s Allegations Do Not Make Sense

FSU’s lawsuit hinges on allegations against Raycom, John Swofford, and his son, dating back to 2008 and 2010. (In the case of Swofford’s son, his role in the athletics department at BC in 2005 is somehow relevant according to FSU.) But all of these allegations raise a red flag: these claims predate the core GOR legal dispute by 5-8 years.

The GORs are at the center of this dispute. They were signed in 2013 and 2016. The temporal proximity gap is obvious, and that gap casts doubt on the relevance of FSU’s accusations against Raycom and Swofford to the actual legal issues. To say it bluntly, FSU’s version of events requires a chronological leap of faith.

Here’s how the timeline unfolds:

- 2008: Swofford and Raycom leaders conspire to save Raycom’s post-SEC life and to keep Swofford’s son employed.

- 2010: The ACC grants its entire media catalogue to ESPN.

- Later in 2010: ESPN sublicenses some ACC content to Raycom.

- 2013: The first GOR is signed.

- 2016: The second GOR is signed.

Crucially, the 2010 ESPN deal happened after the alleged wrongdoing (2008-2010) but significantly before the GORs (2013-2016). This highlights the fundamental disconnect between FSU’s accusations and the actual legal dispute.

In essence, FSU’s attempt to bridge the 5–8-year gap between its claims and the GORs creates a temporal chasm that undermines its legal foundation. Without proof of a direct and contemporaneous impact on the GORs, its argument appears more like a historical grievance than a legally relevant concern.

FSU Continues to Misunderstand the Nature of the GOR as a Copyright License. Given the Lifespans of Intellectual Property Rights, Long-Term Contracts Like the GOR Are Common.

I have written about the GORs in the context of intellectual property law here, but FSU’s most recent complaint spends a lot of time discussing the GOR’s duration and deeming it unreasonable. However, the GOR is not a typical commercial contract; it is a copyright license agreement. This distinction explains why the GOR’s length and terms are considered legally permissible.

Unlike “run-of-the-mill” contracts like non-compete agreements, copyright licenses deal with intellectual property (IP). IP rights, such as patents, copyrights, and trademarks, inherently last longer than the typical subject matter of standard commercial agreements:

- Patents: Typically last for 20 years, with easily attainable extensions for enhancements.

- Copyrights: Typically last for the author’s life plus 70 years.

- Trademarks: Can last indefinitely with active use.

- Trade Secrets: Protection lasts as long as they remain confidential and valuable (here, think of the storied Coca-Cola recipe), and not easily subject to reverse engineering.

As you can see, IP lasts a long time, and this is especially true, and perhaps egregiously so, for copyrights that are at the center of the FSU-ACC dispute. But it is not abnormal, and it is how copyright holders monetize their copyrights. For example, think of how Disney seemingly controlled Mickey Mouse for what seemed like an eternity, or how George Lucas continues to exploit the Star Wars genre 47 years after its release. Consider also how Elvis’ family continues to enjoy music royalties, despite Elvis having passed away in 1977.

These extensive durations reflect the longevity of IP assets, and it is why copyright licenses are often structured for protracted terms. Therefore, a longer-term agreement is not only acceptable but also aligns with established legal principles for IP licensing.

Imagine FSU’s Chief Osceola searching for his spear – that’s how misplaced FSU’s GOR arguments are from an IP perspective.

There May Be Alternative Explanations for the ACC’s Revenue Woes

Setting aside claims of mismanagement and self-dealing, I suggest that there is a simpler reason the current ACC-ESPN deal seems unfavorable; my perspective, though speculative, diverges from FSU’s narrative that blames figures like Swofford or alleged mismanagement.

Performance Milestones

In sports media deals, clauses tied to viewership and subscriptions are common, likely present in the ACC-ESPN agreement. These clauses allow adjustments based on the success of key games or network growth, ensuring fairness and competitiveness. I stress that I am speculating, but the SEC’s renegotiation success might be due to such metrics exceeding expectations.

FSU compares the ACC to the SEC (and Big Ten) as if they were apples-to-apples. They are not. As a Clemson, SC native, a Duke graduate, and a parent of a UNC-Chapel Hill student, I hate to admit what follows: unlike the SEC, ACC sports do not “just mean more” to those living in the localities of several ACC schools, and that has possibly had an impact on the ACC’s ability to meet certain performance milestones.

Large cities like Boston, Miami, Pittsburgh, Atlanta, and Syracuse face challenges in fostering strong fan engagement for their ACC teams. These cities offer a multitude of entertainment options, including professional sports and other college programs (e.g., UGA), that vie for fans’ attention. This competition undoubtedly weakens overall enthusiasm for the ACC, as evidenced by the paltry attendance of a Georgia Tech at Pitt game.

Compounding apathy is the ACC’s lackluster performance in football over the past two decades, save for the dominant exception of Clemson. This persistent underachievement has resulted in underwhelming matchups and a widespread perception that the conference unimportant and weak. While I am speculating, this perception inevitably undermines the appeal and viewership of ACC football games (for all tiers), creating a self-inflicted cycle of diminishing interest.

Consequently, it is possible that the ACC Network’s subscriber growth has been only modest, with a possible decrease in viewership for premier Tier 1 ACC football games. In fact, the traditional rivalry of Miami-FSU may have lost its Tier 1 status, leaving FSU-Clemson as the standout high-stakes matchup for the ACC.

The point is that the issues plaguing the ACC go beyond FSU’s grievances about mismanagement, the GOR, or the GOR’s duration. Though I am speculating, it is entirely possible that the ACC hasn’t hit the performance milestones necessary for renegotiation, leaving ESPN with zero contractual obligation or financial incentive to rain more money on the ACC.

While the above is grounded in informed speculation, the absence of the actual ACC-ESPN contract necessitates some assumptions. Despite this, the reasoning feels solid, underpinned by industry norms and observable trends. Access to the contract would undoubtedly clarify these speculations, providing concrete evidence to either support or refute my conclusions about what may be holding back the ACC.

It’s Also Possible that the ACC Presidents Simply Miscalculated

Otherwise, looking back at the 2013 and 2016 GOR agreements, it’s easy to wonder if the ACC, especially including FSU, miscalculated the future value of its media rights. At the time, a potential decline in value seemed plausible, given emerging trends like cord-cutting and the uncertain future of the traditional pay-TV model.

However, what nobody could have predicted was the dramatic shift in the media landscape. Cord-cutting accelerated, but instead of displacing live sports, it fueled a demand for content consumers could access without traditional cable packages. Suddenly, live sports stood out as one of the few compelling reasons to subscribe to streaming services, attracting both viewers and advertisers in droves. This unforeseen surge in demand sent the value of live sports rights skyrocketing, leaving the terms of the GORs seemingly outdated in hindsight.

Conclusion

I believe all schools in the ACC need a better financial situation. I understand FSU’s frustration, and I would like to help my ACC schools of Clemson, Duke, and UNC (in that specific order) get into a better financial situation. (Never pull against Clemson, always pull for Duke against UNC, and pull for the Heels when I am with my child or otherwise have no place to escape.) Legally, however, I simply can’t find a way for any school to get out without paying a ton of money.

In the end and regarding FSU’s amended complaint, though, it is no FSU Tomahawk Chop. As demonstrated above, I harbor deep skepticism towards FSU’s narrative of fraud, coercion, misrepresentation, and the events surrounding Raycom-Swofford and the GORs. The FSU administrative players were undoubtedly informed or capable of being informed, and nothing can overcome the fact that FSU signed the GORs twice and benefited from them. These facts, coupled with a complete lack of substantive contract defenses and the enduring nature of the GOR as a copyright license, leave FSU facing immediate dismissal challenges or an early summary judgment order.

“Viewpoints” on Chapelboro is a recurring series of community-submitted opinion columns. All thoughts, ideas, opinions and expressions in this series are those of the author, and do not reflect the work or reporting of 97.9 The Hill and Chapelboro.com.