In the spring of 2020, everything changed.

Everything changed first over COVID-19. People worked from home, others lost their jobs. Overnight, our plans changed. Our needs changed. And the organizations we counted on to meet those needs – they had to change as well.

And something else was happening too. The same week North Carolina closed its schools, a woman named Breonna Taylor was shot and killed by police in Louisville. Two months later, George Floyd was killed in Minneapolis. And as people flooded the streets in protest, once again, we realized things had to change.

It’s now been three years since that spring. What have we learned from our experience? What lessons have we taken away? What changes have we made? And which of those changes will last?

“Three Years” is a series by 97.9 The Hill’s Aaron Keck – looking back on our memories and lessons learned from our collective experience, drawn from conversations with numerous government officials, nonprofit heads, scholars and thought leaders in the Chapel Hill-Carrboro community.

Click here for the entire 15-part series.

Listen to Chapter 2:

Chapter 2: The Pivot

The reality of COVID-19 hit everyone simultaneously in the space of a week. People stopped going out, businesses and organizations started to close. And by that Friday, closures, cancellations and shutdowns were everywhere.

Then came the pivot.

“I remember it all changing in one week’s worth of time,” says Rachel Bearman, the executive director of Orange County Meals on Wheels. “We started the week with hot meal deliveries – and maybe two of our recipients were getting frozen meal boxes, because they could not be available during delivery times to suit their needs. And I remember calling our caterer and saying, ‘I know we do two frozen boxes with you (each) week, but – what would it be like next week if you delivered us 180 frozen food boxes? Would that be possible?’”

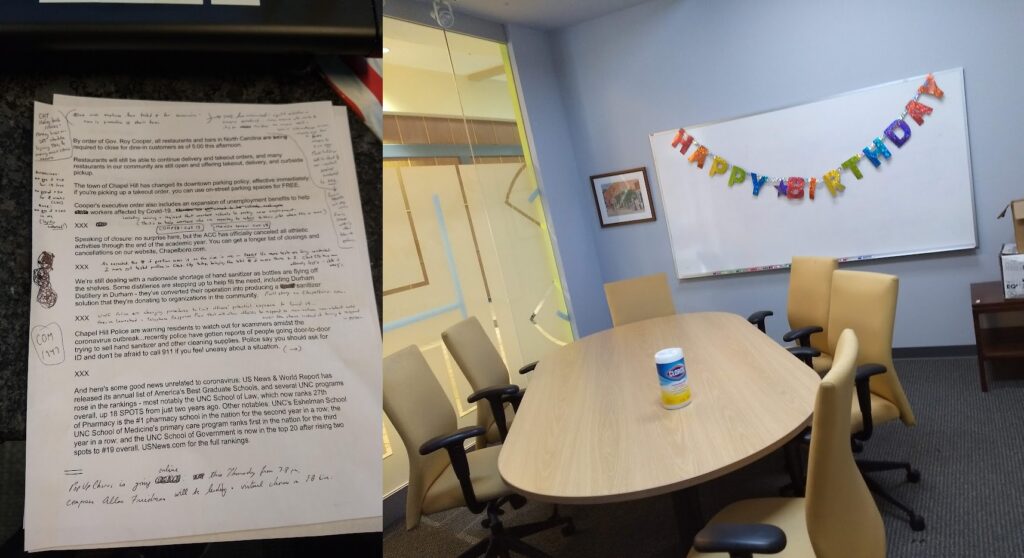

March 17, 2020: while one of my coworkers was experiencing a very sad birthday party, my script for the afternoon news was changing rapidly as new information kept pouring in.

In Pittsboro, the Chatham Outreach Alliance, CORA, was having issues of its own.

“We went through a couple of days of denial,” says executive director Melissa Driver Beard. “(Then) I guess it was March 16 or 17: we walked into the pantry, looked around, and – I think my quote was that ‘we were gonna Chick-fil-A the heck out of this thing.’ And you know, within hours we were outside serving in a drive-through setup. People were in the hallways bagging bags of groceries. And it wasn’t until a little bit later that I think we all sort of looked around and thought, ‘okay, wow.’ Nobody ever said, ‘let’s don’t do this.’ Nobody ever said, ‘let’s go home, we don’t want to be here, we’re afraid.’ We just kept going.”

“How did you handle volunteers?” I ask her. Back in 2020 she’d been the one who clued me in to the fact that many nonprofits rely on volunteers who were senior citizens – exactly the people who were most at risk of COVID, who were being told to stay home.

“You know, we kept them for a little while,” she says. “I would say until about April. And then – when things really started to get bad, and everybody became a little bit more aware of what COVID was all about, I didn’t want to knowingly put volunteers in harm’s way. And so I sent them home for – I guess about a good six weeks.

“They were angry about it! They didn’t wanna go home. They wanted to stay and help.”

At Orange County Habitat for Humanity, construction VP Richard Turlington and executive director Jennifer Player were facing a similar dilemma.

“Our regular weekly volunteers are all older and retirees,” Turlington says.

“And UNC students,” Player adds. “We use a lot of UNC students – and they all left town.”

Back at Meals on Wheels, Rachel Bearman still had her volunteers – and lots and lots of food boxes.

“I look back at pictures from that time,” she says. “We were at Binkley Baptist Church at the time, this was before masking and before separating – (and) I think we had about 50 volunteers in a room sorting hot meals, packages of fruit desserts, and 180 frozen food boxes in the hallways, like in any nook and cranny that could fit into the space. And all these people sorting by route and who needs what and what goes where.

“And we thought that would give us at least a week to figure out – what do we do next?”

That was a question that all of us had to answer, with very little information.

“I remember at the time we had conversations like, ‘if the plumber comes in, do I need to then sanitize every surface in the unit?’” says Richard Turlington. “And for a couple months we were doing that. We were spraying down every countertop, every doorknob – any time anybody else went into that unit that wasn’t our site supervisor, they would spray it all down…

“I mean, there was a period where we were spraying down every hammer. Some people were (even) like, ‘should I lay out the nails and spray those down?’”

And while nonprofits were making those choices for themselves, local government officials had to make decisions on behalf of the entire community.

“We didn’t know what we didn’t know,” says Chapel Hill Mayor Pam Hemminger. “And it was hard to get information at first. The federal government wasn’t doing anything. And the state government was trying its hardest to figure stuff out. So the Orange County leaders, we got together with the health director and said, ‘let’s make these decisions.’ So we pulled (a committee) together really quickly, UNC and UNC Health and all the different emergency groups, to talk through what we needed to do…

“And you know, PPE wasn’t a thing either. We didn’t know what we needed. We didn’t know how to slow the spread other than what the CDC was telling us. And then they were waffling on masks. So we were like, ‘okay, well, how do we take that bold step?’”

At Meals on Wheels, meanwhile, Rachel Bearman and her staff managed to complete a total transformation of their service model in the space of one week.

“We limited our volunteer access,” she says. “We were only going to deliver once a week, so we would have less contact between volunteers and recipients. We started a phone brigade, since we were no longer going into homes or being able to spend time with people. We essentially started our own food pantry, delivering emergency food and supply boxes, because now our people had even less access to food.

“In one week’s worth of time, we sort of upended our entire program and switched to something else.”

March 23, 2020: trying to maintain a positive attitude while posing with that day’s guests – who were all on the phone.

And very quickly, in spite of everything, people figured out ways to step up and meet the needs that had suddenly, unexpectedly, materialized.

“We would just put out calls,” Bearman says. “There were basic things we didn’t have, like toilet paper and tissues, even bags to package our things in – and we would show up at our door and there would be piles of stuff. The community would have just dropped off whatever we (requested). And that’s really what enabled us to kind of make that – that ‘pivot,’ the word of the pandemic, and keep going.”

At CORA, without volunteers, a staff of eight people found themselves doing the job of several dozen – and figuring out how to make it work.

“You have to look at the positive, especially during this time,” says development and communications director Rebecca Hankins. “We were all working together – and my job is a desk job, (but) all of a sudden I’m out there loading cabbages in the trunks and talking to people and ending the day sunburned and tired. And it wasn’t only the physical work, it was the camaraderie. You know, you’d get an email and it’d be like, ‘oh, we want you to apply for this grant, you have 24 hours to get back to me.’ And so we’d be on the phone at 11:30 at night, sitting at my dining room table – we were all taking on things that were just out of the ordinary.”

They were also finding information from sources that were out of the ordinary, too.

“It’s like flying a plane while building it,” says Mayor Hemminger with a laugh. “We were really struggling with getting real information out to folks: we wanted to make sure our information really was based on science, and when you’re not getting the support from the federal or state (governments) or the CDC, we were getting our science from UNC, who’s actually one of the leaders in this…

“And then I’ll tell you, it was interesting: Bloomberg and Johns Hopkins got together and started holding seminars for mayors nationally. I mean, they had real science and real data.”

And fittingly, for a community that prides itself on public service, even the senior volunteers came back to help.

“As the pandemic progressed,” says Rachel Bearman, “we had a number of very persistent volunteers who were 65 and older who said, ‘you know, we have come to understand what this is. We are willing to take this risk. This is a decision we are making.’

“And we said, ‘okay.’”

Click here for the entire 15-part series.

Featured image: cars lined up at the Eubanks Road park-and-ride lot for food distribution in 2020.

Chapelboro.com does not charge subscription fees, and you can directly support our efforts in local journalism here. Want more of what you see on Chapelboro? Let us bring free local news and community information to you by signing up for our biweekly newsletter.