Often attributed to Mark Twain — perhaps mistakenly, since no historical source shows he actually made the statement — “History doesn’t repeat itself, but it often rhymes” is a common and apt refrain when discussing the connection between historical perspectives and current events. By drawing on knowledge of what happened in the past, and why, we are better able to understand the flow and direction of the history collectively created in each new day.

“Past Rhymes With Present Times” is a series by Lloyd S. Kramer exploring historical context and frameworks, and how the foundations of the past affect the building of the future.

The recent actions of authoritarian regimes and the dehumanizing violence of current global conflicts evoke haunting historical memories of anti-democratic violence and warfare in the 1930s and 1940s. The fragility of human rights and human life, however, may appear most painfully in the resurgence of genocidal attacks on whole groups of people who are now facing extreme existential dangers in their own homelands.

The historian Timothy Snyder argues, for example, that the Russian war against Ukraine is a genocidal campaign to destroy the existence of the Ukrainian nation and the autonomous culture of its people. Other experts on the history of genocide such as the Israeli-American historian Omer Bartov describe Israel’s destruction of Palestinian families, children, homes, schools, hospitals, and economic life as a genocidal war in Gaza; and the New York Times Columnist Nicholas Kristof has written about the genocidal violence and starvation tactics that are killing millions of vulnerable Africans in Sudan.

Each of these present-day conflicts is therefore sparking new debates about the “crime of genocide,” but the origin and meanings of the “genocide” concept are often obscure; and few North Carolinians know that the most influential early descriptions of genocide emerged in the analytical research of the Polish-Jewish exile Raphael Lemkin while he was working at Duke University in 1941-42.

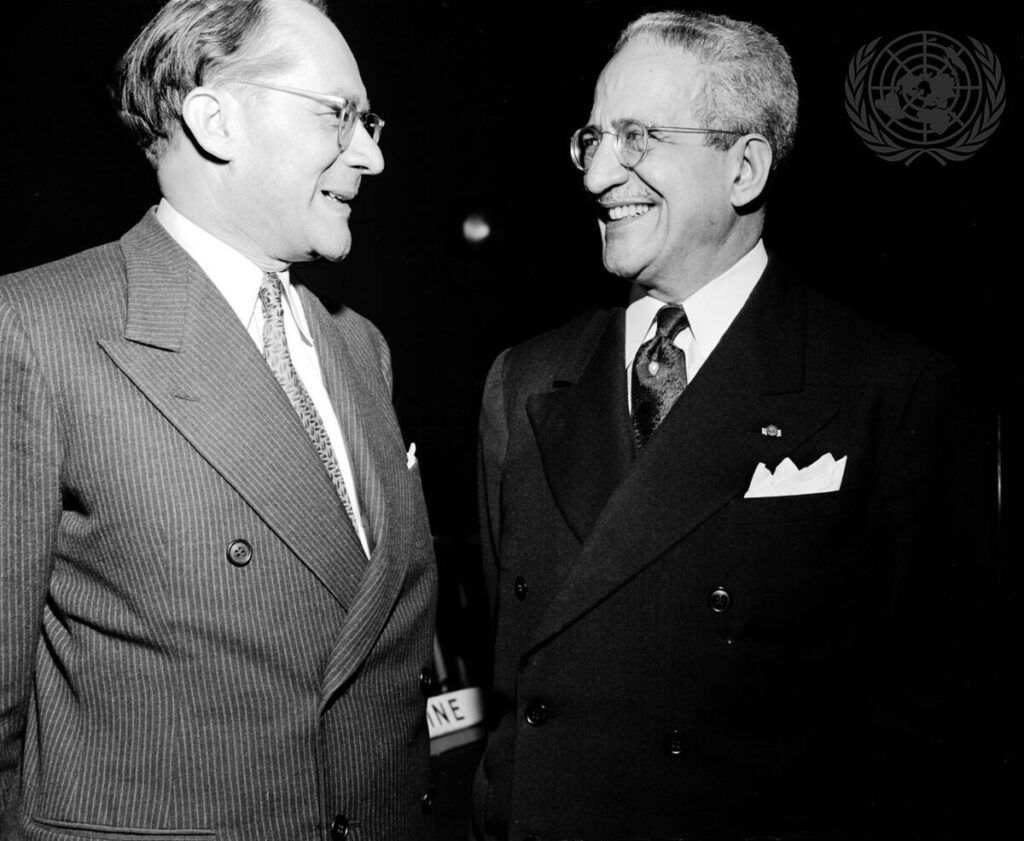

Professor Raphael Lemkin, left, originator of the Genocide Convention and Ricardo Alfaro of Panama, chairman of the Assembly’s Legal Committee, in conversation before the plenary meeting of the General Assemby at which the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide was approved, in Palais de Chaillot, Paris. (photo via UN.org)

Raphael Lemkin and Duke University

Lemkin (1900-1959) had studied law at the University of Lviv during the 1920s, when Poland briefly controlled the city of Lviv and other central European territories that are now within Ukraine.

Lemkin became interested in the vulnerability of scapegoated people as he learned about the Ottoman Turkish government’s killing of more than one million Armenians during the First World War, but he also wrote an early book on Polish legal codes which led to his friendship with a Duke law professor named Malcolm McDermott who visited Poland in 1936.

McDermott collaborated with Lemkin to publish an English translation of his book, so the multilingual Polish lawyer corresponded with the American professor after escaping from the Nazi invasion of Poland and reaching Sweden in 1940. This communication opened a pathway out of Europe when McDermott offered Lemkin a “visiting position” at Duke and facilitated his application for an American visa that allowed him to move from Sweden to North Carolina.

Lemkin therefore made an incredible journey across the Soviet Union to Japan and found a ship to Seattle—from where he traveled by trains to Durham. He finally arrived at Duke on April 23, 1941, without money or possessions or any previous experience in an English-speaking country, but he carried bags of rare documents about Nazi occupation policies and anti-Jewish atrocities. This material provided primary sources for numerous talks on military governments in political science classes and for public lectures that Duke professors helped to arrange in North Carolina towns.

Duke University’s librarian for Slavic and East European studies, Ernest A. Zitser, has written a valuable account of Lemkin’s “intellectual interlude” in Durham (North Carolina Historical Review, 2019) which includes a listing of Lemkin’s 13 public talks at local clubs and organizations on topics such as “Aspects of War in Eastern Europe” and “Law and Lawyers in the European Subjugated Countries.”

He launched his provocative public talks at a dinner for Duke alumni, where he stressed that Hitler was destroying “whole peoples” and where he may have startled the audience with his stark questions. “If women, children, and old people would be murdered a hundred miles from here,” he asked, “wouldn’t you run to help? Then why do you stop this decision of your heart when the distance is five thousand miles instead of a hundred?”

As Lemkin noted in a later description of his bleak presentations about mass killings, “People would come and say to me [after my talks], ‘I am ashamed that we are standing idle and watching innocent people being slaughtered.’”

The Meaning of Genocide

Lemkin was not yet using the word “genocide” in his discussions with North Carolinians, but he was working at Duke to collect the evidence and develop the concept that he would introduce in a book he published after becoming a government consultant in Washington, Axis Rule in Occupied Europe (1944). This book’s ninth chapter, which was entitled “Genocide,” became Lemkin’s most influential contribution to an argument about genocidal violence that still resonates today.

Calling genocide a “new term and new conception for the destruction of nations,” Lemkin explained that the Greek word genos (meaning race or tribe) could be linked to the Latin word cide (which meant killing) to describe “coordinated” plans to destroy the “essential foundations of the life of national groups” and to achieve the “aim of annihilating the groups themselves.”

The goal of genocidal policies was thus to displace and demolish a targeted population and then to impose the oppressor’s own national culture on the land of the displaced people. The project of genocide began with the destruction of all self-governing political institutions in the occupied territory, but genocidal policies also destroyed schools, universities, teachers, journalists and other well-educated persons who had always been “the main bearers of national ideals.”

This systematic destruction of social and cultural life was closely linked to the “crippling” of economic institutions that supported the livelihood of targeted populations, but the economic destruction contributed to the even more devastating “biological” goal of depopulation through drastic reductions in food supplies.

Starving people were thus “deprived of elemental necessities for preserving health and life,” and the debilitating starvation soon reduced “the survival capacity of children born of underfed parents.” The death of children was justified with the dehumanizing assumption that still-innocent children could grow up to revive the national group that might again endanger the people waging the genocidal campaign.

Lemkin defined genocide as a “punishment” for people who were guilty of no crime except their birth into a specific social group. Their deaths were in fact the real crime, but the legal scholar Phillipe Sands has explained how this concept of genocide differed from the equally influential concept of “crimes against humanity,” which argues that the victims of systematic killings lose their individual human rights even when the destruction of their social group is not the explicitly stated objective of government-organized violence.

As Sands notes in his excellent book on this individual/group distinction, East West Street: On the Origins of “Genocide” and “Crimes Against Humanity” (2016), the prosecutors at the Nuremberg Trials in 1945-46 adopted a more limited legal strategy by charging Nazi leaders with the most provable “crimes against humanity” and avoiding the more wide-ranging definitions of genocide that Lemkin had proposed.

Lemkin’s campaign to make genocide an international crime continued after the Nuremberg trials, however, as he strongly encouraged members of the newly established United Nations to create a “Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide.”

This international agreement, which the UN General Assembly approved in December 1948, described genocidal acts as policies that destroyed “in whole or in part, a national ethnical, racial or religious group” and included specific crimes such as “forcibly transferring children of the group to another group.”

Lemkin’s detailed descriptions of cultural genocide were dropped to ensure approval of the UN Convention, but even these concessions did not satisfy the critics who blocked its ratification in the US Senate. Southern political leaders such as North Carolina’s senators Willis Smith and Alton Lennon opposed the Convention on Genocide as a threat to national sovereignty or because they feared it might be used to condemn anti-Black racial segregation and the systematic displacement of Native Americans.

American advocates of the UN Convention eventually convinced the US Senate to ratify the statement in 1988, and more than 150 nations have now endorsed its legal principles. Meanwhile, judicial mechanisms for enforcement were gradually established through the International Court of Justice [ICJ] (created in 1945) and through the International Criminal Court [ICC] (created in 2002), and charges of genocide against the recent actions of Benjamin Natanyahu and Vladimir Putin are still awaiting final judgments in these two courts.

Lemkin’s account of genocidal policies seems applicable to Israeli and Russian policies in Gaza and Ukraine as well as the Sudanese Civil War, but it has always been more difficult to prosecute government leaders for crimes of intentional “genocide” than for “crimes against humanity,” which suggests why the current court cases may also produce ambiguous outcomes.

Lemkin and the Continuing Dangers of Genocide

Although his classroom presentations and public talks introduced North Carolinians to the meaning of genocidal goals and actions, Lemkin noted in a later memoir that “genocide is so easy to commit because people don’t want to believe it until after it happens.”

He nevertheless envisioned a better world in which genocidal killings would be condemned and prosecuted in international courts. Summarizing his hopes for “The World of Tomorrow” at the Raleigh Women’s Club in October 1942, Lemkin imagined a future era in which international organizations would promote “individual rights, internationally protected living standards for nations and groups, international education, and international justice.”

If an exiled Polish lawyer could sustain this view of “tomorrow” during the brutal Nazi destruction of people and cultures in eastern Europe (where he lost almost all his own Jewish family in the Holocaust), then North Carolinians should be able to reaffirm similar aspirations in 2025. Genocidal actions continually reappear in new places, but Lemkin-like condemnations of such murderous actions also reappear in the continuing defense of humane values and in every struggle to build stronger systems of international justice.

Photo via Lindsay Metivier

Lloyd Kramer is a professor emeritus of History at UNC, Chapel Hill, who believes the humanities provide essential knowledge for both personal and public lives. His most recent book is titled “Traveling to Unknown Places: Nineteenth-Century Journeys Toward French and American Selfhood,” but his historical interest in cross-cultural exchanges also shaped earlier books such as “Nationalism In Europe and America: Politics, Cultures, and Identities Since 1775” and “Lafayette in Two Worlds: Public Cultures and Personal Identities in an Age of Revolutions.”