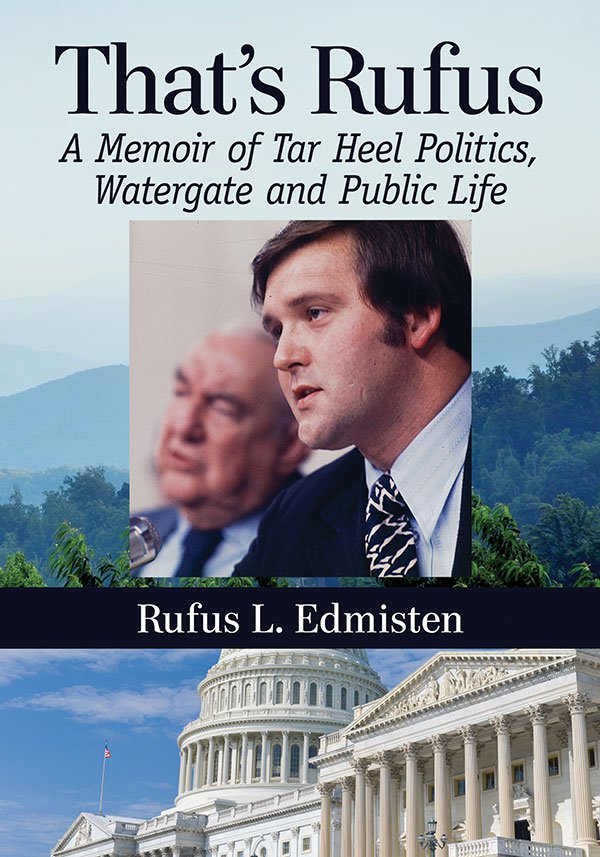

What lessons can we learn from one of North Carolina’s most colorful political figures who served as attorney general, lost a gubernatorial election, won election as secretary of state, lost that position in disgrace, and then came back as a successful lawyer and lobbyist?

In a recent column about Rufus Edmisten’s book, “That’s Rufus: A Memoir of Tar Heel Politics, Watergate and Public Life,” I promised to share lessons from that book.

In a recent column about Rufus Edmisten’s book, “That’s Rufus: A Memoir of Tar Heel Politics, Watergate and Public Life,” I promised to share lessons from that book.

Edmisten’s most important lessons are gathered in a chapter titled “Hubris” near the end of his book. Writing that although he could find excuses for his “bad behavior” as secretary of state, he confesses, “It was nobody’s fault but my own. This has not been easy to accept, but sometimes the truth isn’t easy to take.”

He compares his conduct with those of the Watergate figures he had earlier helped bring down as an aide to Sen. Sam J. Ervin. Edmisten writes that he, like them, “brought catastrophe upon themselves in part by becoming full of themselves, feeling a false sense of entitlement and making unwise choices.”

Edmisten explains how his long years in office and in the public spotlight led to his problems. “Getting too impressed with myself resulted in bad things happening to me. When you hold public office or any position others perceive as one of power, a lot of people say a lot of nice things about you. While some of them might be true, many of them are simply intended to win favor. This works about as often as you might expect you really can catch more flies with honey than you can with vinegar. It can also really puff a person up. Everybody wants to be liked, after all.”

His situation came to a head in 1995.

“I had been doing some things that were foolish, to say the least. As I perceived myself to be more and more powerful I danced closer and closer to an edge I should never have gone near. I didn’t intend to do wrong. I was just playing loose and easy with some rules I should have abided.”

A report by the state auditor and articles in the Raleigh News & Observer alleged, according to Edmisten’s book, the misuse of employees, misuse of a state car, abuses by subordinates and improper hiring practices.

In this deluge of criticism, Edmisten announced he would not run for reelection, and, he writes, “I actually thanked God my daddy had died before this mess started.”

Why did it happen? That is Edmisten’s lesson for us.

It was the excessive pride that arose from his long years at the center of public attention that led to his troubles.

He warns his readers, “Once hubris gets a foothold it grows incrementally and accelerates until it is expanding exponentially, and in leaps and bounds takes over. No doubt the sycophants of the world recognize the hubris-infected when they see one and scamper to that person like crows to a fresh corn field. They converge and the convergence only adds to the inflated sense of self-worth of the Terrible Toad of Hubris because they are all paying attention to him. I forsook the humility that my upbringing instilled and became enthralled by the deluge of flattering attention.”

This lesson about the dangers of hubris is not the end of the story. In inspiring chapters at the end of the book, Edmisten chronicles how his wife and friends led him back into the practice of law and other areas of service. His wife told him, “We are not going to whine.”

“At the age of fifty-five,” he writes, “I put aside all petty things and began a new life.”

In making his new life, Edmisten gives us another lesson.

It is never too late to turn an old life into a new one.