Story by Mary King, Photography by Daniela Rodriguez-Puente, Video story by Nick Perlin

Priyav Chandna has some questions.

“What could you do here?”

“What can this knight do?”

“Do you see the checkmate?”

As Chandna tests his student’s comprehension, he glances down through clear frame glasses at the array of green and white squares before him. At the beginning of the lesson, he had unsheathed this vinyl board from a cylindrical zip-up bag and unfurled it onto the table. An intellectual placemat.

If he were still his childhood self, Chandna might have been calculating his next move. Assessing his vulnerable spots. Anticipating his opponent’s next attack. His competitive chess career took him all over the world, from Brazil, to Slovenia, to India.

But here and now, at 21 years old, the UNC-Chapel Hill student isn’t concerned with dominating the chess board. All he wants to do is help the mind across from him understand it.

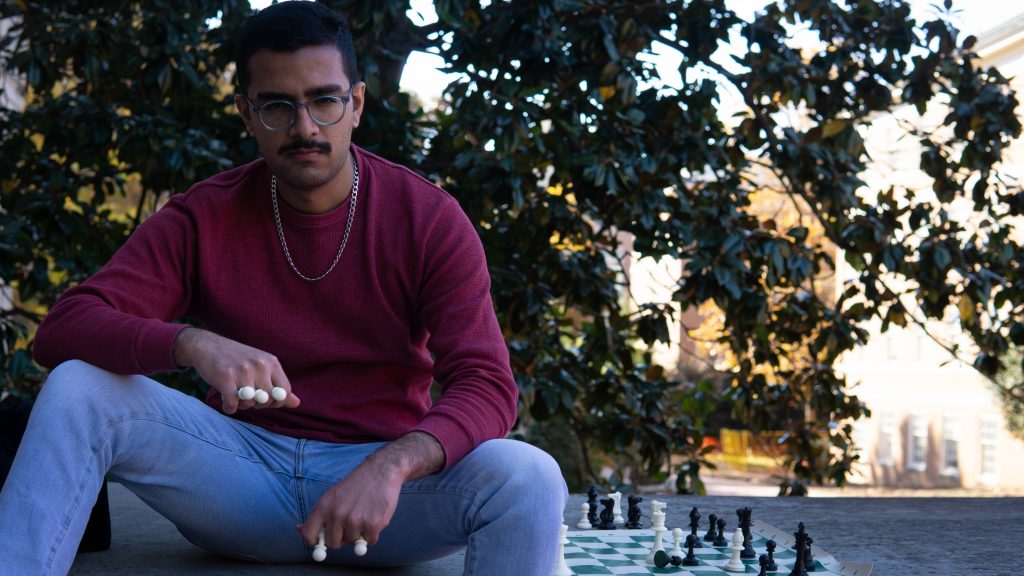

Priyav Chandna sets up his chess practice board on the steps of Wilson Library. A competitive chess player when he was younger, Chandna now dedicates his time to teaching the craft. Photo by Daniela Rodriguez-Puente.

Chandna oversees the chess education of nearly 300 students through MyChessTutor. He founded the online chess academy in his first year of college. Chandna handpicked 24 instructors from around the world to teach using Zoom and a virtual chess board.

The pandemic, combined with the popularity of the Netflix series “The Queen’s Gambit,” led to a boom in chess. The academy received an influx of students as a result.

“I think we’re still riding that wave today,” he says.

‘This kid is good’

When Chandna teaches chess, he doesn’t lecture. He engages. He gleaned this philosophy from one of his childhood instructors.

“Lessons were fun,” Chandna says. “They were conversational. There was humor.”

That style of teaching worked for him: He represented his home country of Botswana twice in the world championship. (“I did OK,” he says. “Didn’t win, but I did OK.”) At one point, he was Africa’s best player under 12 years old. He’s achieved the International Chess Federation rating of Candidate Master and currently ranks within the top 2% of all chess players in the U.S.

“On occasion, I see him doing his teachings online,” says Shubham “Shubz” Chandna, his older brother. “He has that passion. That same joy and happiness, he wants to give and instill in others who love the game.”

For Priyav Chandna, all of it — the championships, the academy, the passion — started 15 years ago, sitting by Shubz at the dinner table.

The brothers were born six years apart in Botswana. Their parents had traveled from India to the southern African country for their honeymoon.

“And they loved it so much, they decided to stay,” Priyav Chandna says.

Their parents enrolled the elder brother in chess lessons as a child.

“Especially being of Indian descent — the world chess champion at the time was Indian,” Priyav Chandna says, referring to Viswanathan Anand. “And so he inspired a lot of generations to play chess, especially Indians.”

Eventually, Priyav became curious and started tagging along. He sat by his brother and the instructor during their lessons at home, watching intently. The lessons weren’t meant for him, but Priyav absorbed them like a sponge. The instructor would ask 12-year-old Shubz questions about chess, and 6-year-old Priyav would pipe up and answer. Correctly.

“He came and jumped in faster than me,” Shubz Chandna says, “and boom! The coach said, ‘This kid is good. He’s sharp.’”

When they played against each other as children, Shubz noticed that Priyav worked at a snail’s pace, thinking through each move with care. So, Shubz would try to get in his head.

“I would do a lot of hanky panky things trying to distract him,” Shubz Chandna says. “I think a byproduct of that is he learned to get away from the noise. But that pressure ultimately was a positive development for him.”

The same year Priyav started lessons, he began competing against other children. Within a couple of years, he was playing in open tournaments and defeating adults.

“That’s the beautiful thing about chess: It has no barriers,” Priyav Chandna says. “All that really matters is your skill level. Like in our chess academy, we’ll notice a little 6-year-old kid crushing 28-year-old Ph.D computer scientists, and the 28-year-old is puzzled. But really, it’s just all about the skill level. How much practice you put in.”

During his summer breaks, Priyav would study chess for about 6 hours a day. With a board in front of him, he’d pore over books that demonstrated moves. Botswana’s lively chess scene introduced him to plenty of rivals.

“I was different-looking in Botswana. But they welcomed me with open arms. They were very supportive. They sponsored me. My chess instructors initially were from Botswana,” Chandna says. “So when I got to represent them, and I did well for them, I felt very proud. It was a big thing for me.”

His jersey — blue and white, the colors of the country’s flag — still hangs in his closet.

“I love Botswana,” he says. “You know, it has a soft spot. And when people today ask me, ‘Where are you from?’ I’ll usually say Botswana.”

A different life

Chandna had a hard time leaving it behind when his family moved to Chapel Hill in 2014, when he was 14 years old. He’d built up all of his friendships in Botswana, and now he was going to have to start from square one.

But some consolation came as he enjoyed a dramatic increase in opportunities to play chess.

“Here, you can really grow, develop, thrive,” he says. “Live the American dream, I guess.”

Chandna spent his first two years in the U.S. at an international residential school in New Mexico, where he became the scholastic state champion. Then he transferred to East Chapel Hill High School. He became the state runner-up twice: once in a scholastic championship, and once in an open championship for all of North Carolina.

As high school graduation crept closer and closer, Chandna found himself at a crossroads. He began to grasp just how much he would have to give up in order to advance farther in the sport.

“The best players in the world didn’t even go to school. All they do is study chess. All they focus on is chess,” he says. “And for me, that was too big of a commitment. And so I realized, ‘Well, I don’t really want that life.’”

With that decision, the sun set on an era that had spanned two-thirds of his life. Looking for a “big environment,” Chandna chose to attend UNC-Chapel Hill and figured he would study philosophy.

But he wouldn’t leave the board behind altogether. The summer before he matriculated, Chandna wanted to make a bit of money. So, he put up flyers in the library advertising chess lessons and began teaching people one on one.

“I just realized I loved it,” he says. “I loved meeting people, getting to know people.”

As his clientele grew, he realized there was potential for something bigger. He saw that a lot of people wanted to learn how to play chess, and he knew from experience that there were a lot of bad instructors out there.

“So, I really wanted to create an outlet that people could trust, where they could sign up and be guaranteed a great experience and learn chess,” Chandna says.

Priyav Chandna. Photo by Daniela Rodriguez-Puente.

He developed a passion for carrying out the business principle of creating value for other people — so much so that he decided to make it his field of study. Chandna says attending UNC-CH’s Kenan-Flagler Business School helped solidify his understanding of accounting, planning, marketing and entrepreneurship.

“If you can create value for your students, make sure they’re having a good time, make sure they’re learning, you will succeed,” he says. “And that’s something I really took to heart.”

‘Just a matter of practice’

Sitting outside of the business school, Chandna glides his finger across the squares on the board. He explains how the pieces move, drawing attention to each black and white figurine with a little tap-tap. He punctuates the conversation with frequent encouragement.

“Exactly, exactly.”

“There we go!”

“You’re doing great!”

Chandna says the instructor is key in shaping a chess player, and it’s essential that they build rapport with their student. If they’re teaching a 6-year-old, they should come down to their level and engage with their humor and silliness. If they’re teaching a student in their 50s, they should take a more mature approach.

“All of our instructors care for our students,” Chandna said. “They have great energy. They’re invested.”

Among these instructors is Venice, or Coach Ven to her students. (Chandna requested to provide only her first name in order to maintain privacy in the client-facing business and avoid her being poached by other chess schools.)

“We have the best coaches out there,” says Coach Ven, who is based in the Philippines. “Priyav actually is really, really picky when it comes to hiring coaches. I myself recommended some of my colleagues, and I think among five coaches that I’ve recommended, he just took one.”

Chandna says he’s had a lot of his students’ parents remark that their children are benefiting from the chess lessons in other areas, like math and music.

“Chess activates so many parts of your brain that you’re not really aware of: logic, creativity, critical thinking, focus as well,” Chandna says. “And you can always express yourself in chess as well — if you’re a very creative person, you can find different ways to express yourself creatively.”

People tend to imagine chess as an erudite pastime for the naturally intelligent to exercise their immense brain power. Chandna doesn’t see it that way. Laughing, he says he doubts he has a high IQ.

“I think there’s that perception where people think, ‘Well, if you’re playing chess, you must be some sort of genius,” he says. “But like anything, it’s just a matter of practice.”

As much as Chandna cherished his years on the competitive chess circuit, he believes teaching is his true calling. He views it as an art: the art of coming to a student’s level. Some students at the academy have gone into competitions and reached the top of their age group in the U.S.

“Besides just the competitive aspect of it, it’s just good to see students enjoying the game, and realizing that they made so much progress that they felt they couldn’t have made before. A lot of students come to us being frustrated, having learned themself and not making progress, but then overcoming that barrier — that’s probably the most fulfilling aspect of it.”

About a year ago, Chandna took a step back from teaching and channeled his efforts toward running the business. But when a new student joins the academy, he still meets with them personally to welcome and get to know them. That scratches his itch for interaction.

When he’s not working at MyChessTutor or doing schoolwork, Chandna enjoys working out and following soccer. He’s ventured into playing poker lately; his chess aptitude doesn’t quite translate.

“I’m pretty bad at poker,” he says. “But I’m learning.”

Chandna views chess as a no-barrier opportunity to connect people of all ages and creeds. He attributes his business’s success to a practiced pedagogy. “I’d say number one, it’s building relationships with students. If you have this label of teacher and student there’s kind of like a hierarchy. It should be more like friendship. A lesson should feel less like a lecture and more like a conversation.” Photo by Daniela Rodriguez-Puente.

Chandna resets his end of the chess board, positioning each piece in its proper square. The royals sheltered in the back. The pawns — “the royal guards” — lined up in the front. He arranges them like it’s second nature.

The student remarks on his speed.

Chandna chuckles.

“Practice, practice, practice.”

Stories from the UNC Media Hub are written by senior students from various concentrations in the Hussman School of Journalism and Media working together to find, produce and market unique stories — all designed to capture multiple angles and perspectives from across North Carolina.

Stories from the UNC Media Hub are written by senior students from various concentrations in the Hussman School of Journalism and Media working together to find, produce and market unique stories — all designed to capture multiple angles and perspectives from across North Carolina.