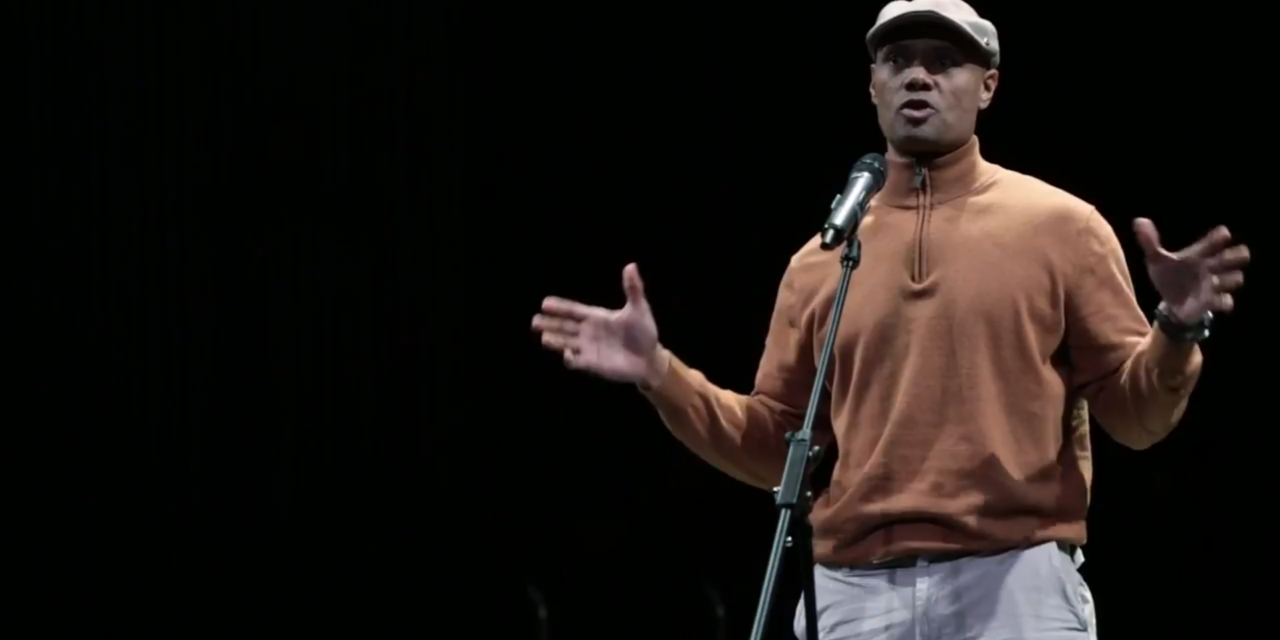

Sonny Kelly is a scholar, teacher, performer, and storyteller currently pursuing a PhD in Communication & Performance Studies at UNC Chapel Hill. Kelly recently joined 97.9 The Hill’s Aaron Keck for a conversation, printed here in its entirety. If you’d like to listen to their discussion, click the link below.

Aaron Keck: We are joined on the phone right now by Sonny Kelly, who you know if you listen to this show on a regular basis. We’ve had him on the air before, he is a graduate student at UNC and the writer of a one-man show called “The Talk.” He also performs in that show, about the talk that African-American parents have to have with their kids about what it means to grow up black in this country. Sonny, thank you so much for being with us today. How are you?

Sonny Kelly: I’m well, Aaron, thank you for having me. Thank you for making space for this conversation.

Keck: Yeah, and thank you. I honestly don’t have specific questions laid out. I really just want to hear from you. So what are your thoughts, where can this conversation begin?

Kelly: Well, I think, I feel, I speak for a lot of Americans, obviously, global citizens, humans, right now when I say that I feel overwhelmed. It’s just a lot to take in. You know, we all need to go through the mourning process when we experience trauma, and I don’t know that we really have allowed ourselves time and space to do so because of so many reasons, not the least of which we’re going through a pandemic, but also we had this cluster of events that have happened between February and this last Monday that are really kind of, they stunned us. And I think, for me, I guess the challenge that I’ve had is a lot of people will contact me because of the work I do with “The Talk” and with youth, in dealing with the school to prison pipeline, and just justice in general, people have asked me, ‘well, how are you doing? Are you really upset?’ And I have to say, you know, I’m not surprised by it. And that’s kinda, that’s a sad thing about this whole thing. When I learned about Ahmaud Arbery, I was angered by the video, but I wasn’t surprised. When I learned about Breonna Taylor, I was angered about the whole story and the details — but again, not surprised. And then finally with George Floyd, it really stung that the, ‘I can’t breathe’ cry was happening again, after it already happened with Eric Garner back in what, 2014? But, sadly, it was kind of more of the same. I think that we have gotten better as a country. Let me say this. I want to give us, as a nation, kudos and respect and gratitude for the fact that we have gotten better. I mean, decades ago, I couldn’t have done the show “The Talk” and had such acclaim for it. I couldn’t have had so many places to perform it, and ways to start these conversations. But sadly, so much of this has happened over and over again. All I can think when I see these videos and I hear the news is ‘well, thank God we have proof now.’ Because I know what’s happening. My ancestors and my elders have known it’s been happening, but so many people look at me when I tell them, ‘Hey, I have to have a talk with my son’ or, ‘Hey, this is this thing with this institutional racism’ or systemic racism or whatever you want to call it. I know those are trigger words for people nowadays, but racism on the structural level, on a societal level, is real and it impacts my life. And when I say that to people, some people just don’t get it and they get offended by it and they want to defend themselves and they want to get into a place where they’re like, ‘well, no, but you must not love the country.’ And I’m not a hater of America. I love my country. I don’t want to destroy or dismantle my country — but I do want to acknowledge the fact that we have some issues, and we have to talk about those issues. And I have to feel safe talking about them without coming off as the “angry black man.” Right? So, I think the conversation starts with saying, ‘look, this stuff that’s happening. It’s not new. George Floyd is not in anomaly, sadly.’ It will say this, it’s more of an anomaly now than it would have been years ago, but this kind of thing is, it’s what we’ve experienced. And we’re so used to just having to suck it up and deal with it and forgive and move on and try to just get some lawyers and get some politicians in place and change policy, but still the stuff keeps happening. We rarely ever get to say, it’s part of a larger pattern. And we need to talk about that larger pattern. So, when the videos came out and the press coverage has come out — to me, that was a bit of, I felt, I felt affirmed. Oddly enough, I felt like we’ll see, there’s exhibit A, there’s more proof. Of course, we’ve had plenty of proof, but I just, I was grateful that someone caught these things on tape. I’m grateful for the folks who picked up their cameras and the folks who publicized and distributed this information so that I can tell the rest of America, ‘y’all, we’re not crazy! See?’ You know?

Keck: Say more about the, you said this up top, the extent to which you saw this and felt trauma. Because I think that’s something that not everyone gets, as well. The extent to which you see this and it’s a traumatic experience, not just for the one person who’s going through it, but for so many other people as well.

Kelly: Yeah. I think what a lot of people don’t understand is that when you look at a person of color, I’ll just speak for myself, as a black boy growing up, I never saw on the television set a black superhero – ever — until I was an adult and “Black Panther” came out. I knew they existed in comic books, but I wasn’t a comic book kid, right? I was a TV kid, and I saw “He-Man” and I saw “Thundercats” and I saw “GI Joe.” And the stars of those were always long flowing hair, blue eyed, white people –which is cool, hey, this is the country I live in that the majority, I’m not angry at that — but I never saw myself as the hero. There are so few times when a black kid, a black person sees themselves in the public eye as the good guy, the hero, the protagonist, right? It’s so rare, but more often than not. When you look at the crime section in the paper, or you look at somebody getting roughed up or arrested you picture, automatically, someone says, ‘Hey, a man was arrested in the park today.’ You almost automatically imagine a black face. So, every time I see crime and it’s placed in a black body, I feel like that’s a projection of me — and I’m not a criminal, I don’t plan on committing any crimes, but it’s still a projection of me because there are so few positive projections of blackness in America. When you see these negative projections, which are common, they are perpetuated. There’s a fetish that America seems to have for showing black criminality and black people being arrested and having negative experiences and being shot and, and death and destruction, et cetera. I’m used to seeing black people bleeding. I’m used to it. I’m not used to seeing positive messages about black people. So, in this country, whenever I see a George Floyd on the ground, I see me, I see my kid, because that’s at the image that I’ve been perpetuated in my eyes since I was a baby, I’ve been conditioned to this. So much so that black people in America experience racism from other black people, as well. It is not a black and white issue. I talk about Freddie Gray and the situation with Freddy Gray in Baltimore. There are a lot of issues that went into his death and to his arrest, so I won’t claim to be a criminal justice expert or a policing expert. I will say this though: I think that Freddie Gray’s death was unjust. There was some injustice that happened there, but three of the people, three of the six officers who were in charge of Freddie Gray’s body from arrest to death were of African descent. So this is not about a white people killing and hurting black people. This is about black bodies being devalued and disparaged and destroyed with impunity and actually being seen as a threat — even in our own eyes. So when I see — let me give you an example. When I told my son about Ahmaud Arbery and I said, ‘Sterling,’ — he knows about this conversation. You know, I do the show, the talk, I teach this stuff — I said, ‘this happened to this young man. He was jogging, he was just 25 years old. He was jogging in this neighborhood. These two guys are white guys, they didn’t think he belonged there. They thought he did a crime and they killed him.’ And the first question my son asked, Aaron, he said, ‘Daddy, was he wearing a hoodie like Trayvon?’ The first thought my son had was, ‘well, could he have done something better?’ So when I see a George or I hear about Breonna, or I see Ahmaud and Trayvon and Tamir — and the list goes on — I see myself, I see my children. And sadly, I had to check myself and remind myself not to blame them for what happened to them, and what’s been happening to them for centuries. We are the stories that we tell. My advisor, Renée Alexander Craft, she said something beautiful to me one day as I was writing my dissertation. She said ‘our stories are the way that we theorize our lives.’ Well, the stories that I hear and the stories that I see in my society, my beloved country, about my people, are stories of violence and of abuse and death and hurt, limitations, silencing. And when you see it again and again, and it’s made viral over the news, it’s just confirmation of what I’ve already been told time and time again from childhood to now. And so it is, it’s a bit of a twisting of the knife in the wound. And when I say that, I say it carefully. Aaron, I’m proud to be an American. I was in the military. I love this country. I don’t feel like this country is daily filleting me and beating me and, and crushing me. But I do feel like the understanding that this country has of a black body is one that sees the black body as fungible as replaceable, as not as valuable as other bodies. So when I see that and I feel that hurt, and I think to myself, ‘man, black lives do matter.’ I’m not speaking in a zero-sum game. Black lives mattering is not in comparison to anybody else’s life mattering. It is my reality. Growing up as a kid in this country that I love, I’ve come to see that I haven’t felt loved as much as I love the country — and in my country and in my world, black lives have not mattered as much as white lives. I’ve seen white people be arrested with gentle demeanor. looked after — for example, take the Dylan Roof arrest. After the shooting, the racial, radicalized shooting and violence, active terrorism in South Carolina, they carefully get this kid and they respect his youth and they’re tender with him. They take them to Burger King to get a meal. Meanwhile, you got a kid getting caught with a nickel bag of weed on the street, you’re getting slammed on the front of a car. And I see that picture over and over again — so much so that I start to think that maybe he deserved it, because the stories that we tell help us to theorize our life. They set up our value systems, whether we like it or not. And so, I’m, you know, there’s a lot of emotion going in, but I think that the wound or the hurt that I feel is not saying, ‘Oh, wow, there’s police brutality. Oh, Oh, wow. There’s racism.’ It’s just seeing it over and over again. And knowing that so often it doesn’t get addressed. And here’s a big thing, Aaron: how many times has that been happening to people like George and Sandra Bland, et cetera. You know, we c need to say their names, how many people have died and been injured and being been humiliated under the foot, the boot of authority — whether it was whether it was a vigilante or a law enforcement officer or a teacher, whatever the case may be. But it was never on tape. How many people have been suffering this and it just never got on tape., so it never went viral, so we were never able to talk about it. These are just tips of icebergs. And I think that’s part of the sorrow. I’ll say that. I think that the most painful thing about this is to know that there are thousands of George Floyds. He just happens to be one that was caught on tape.

Keck: You’re speaking with Sonny Kelly, again, the author of the one-man show ‘The Talk,’ and you’re speaking to something that has been on my mind for the last couple of days, which is I walk into the studio and I turn on the mic and I talk for a living, but this has happened so often before. And everything that needs to be said about this has been said before. And it’s been said so many times, and the people who need to hear it have heard it already so many times, and it’s just not sinking in for folks. So I, over the weekend, I’m thinking about what can I say, what can be said, that’s actually gonna matter. That’s actually gonna make a difference. You have written ‘The Talk’ you’ve gotten up on stage. You’ve performed this. You’ve reached out to so many people. How have you been able to make your words matter?

Kelly: Thank you. I think that I’m really grateful for the fact that crisis pushes people to seek solutions they wouldn’t have otherwise sought. Right now I’m working with state Senator Kirk deViere here in Fayetteville to produce an online version of ‘The Talk’ — an excerpt of it — that will lead to a community discussion. We’ll be doing that in the next couple of weeks. I’m also working with my friend Tru Pettigrew and Drew Godwin out in Cary, they’re building bridges and doing a barbershop rap session between police officers and community members. And they want, we’re going to work out, also a performance of ‘The talk,’ a virtual performance of ‘The Talk,’ and then a Zoom conversation or some kind of virtual conversation. You know, my thought is I need you to stay in the room with me. We have talked about these facts before, but in terms of dealing with the truth of it, if we’re honest, so many black people have held back the truth because we don’t feel safe sharing it because we’re afraid we’re going to be seen as the ‘angry black person’ or as rehashing history or as not being resilient enough, as ‘pulling the race card.’ So we rarely ever get to sit down with white people and tell the truth from our hearts and our minds and allow the tears or the anger or frustration to come out without pointing fingers, without calling people out. But just calling people in and saying, ‘this is my hurt.’ On the other end, so many white people, they don’t want to have the conversation. They they pull back from the conversation because they’re afraid of being called out — and they may feel guilty or angry or frustrated because they see themselves as colorblind and not racist. And I hear you, and I’m thankful that you are color blind in your own way and not racist, but in America, you can’t be colorblind. And the sense that we all are born, seeing color, like I said, as a child, I’ve been socialized to understand what a black body means — that wasn’t my doing. It’s been trained in me in many different ways. So what I would like to see is people, instead of rehashing all the details and the facts, let’s talk about our truth. Let’s talk about how that landed with me. When I saw George on the ground, and I heard this human being crying out for his life, and he was one of mine — not that I’m in a tribe and I’m separate from America, but I have been racialized by being born in America. I don’t want to, I’m just not identity politics. I don’t want to be separate. I don’t want to be lesser than, but oftentimes am made to feel that way. And it’s not just in my head, please understand it’s not in my imagination. And if we can get to this place where we can just tell our honest truth and affirm them, right? Even if we disagree, but affirm that truth, we can get to a place where we can start talking about policy and about, about police accountability. I love police officers. My grandfather was a police officer. Some of my friends are police officers. One of my good friends is a Sheriff’s deputy in Cumberland County, and I asked him about this. And he said, ‘you know what?’ — and he’s a white man — he said, ‘at the end of the day, I just want you to get home. And I want me to get home safely. That’s my goal, right?’ So I know it’s a, it’s a complicated story, but if you will, let me just share my truth and share my hurt, honestly. And we let white people share their guilt and their concern and their ignorance. And I don’t say it in a negative way. I mean, ignorant, just meaning you don’t know. So you don’t know because we haven’t shared, so let’s be safe in this and let’s not pull talking points out. Let’s not pull statistics out. Let’s just talk about how this landed in your heart and your body and your household. And let’s talk to our kids and figure out how we’re going to talk to our kids. And then once we know that we care, cause nobody cares how much you know ‘till they know how much you care, now we can move toward policy and police accountability and how we’re going to invest in after school programs and how we’re going to start to figure out who we’re going to vote for, and who’s got a good clean record on this kind of thing on fairness and justice, regardless of their racial background. Right? But what we try to do is we try to frontload the policy and the political change – and what that does is it polarizes us again, and we go left, we go right, and it’s all or nothing talking points and nobody’s listening, right? So that’s what the talk does. It’s just one daddy on a stage crying, trying to figure this thing out, telling you what his grandmother told him, what his father told him, telling you the story of his mother, telling the story of this beautiful little brown boy in his backseat. How he’s trying to figure out how to tell him ‘you live in a great country son, but this country, people in this country don’t always see you as great as you are. And one day they will. And I hope they will.’ I hold onto hope. I’m not a pessimist. I don’t agree with looting. I don’t agree with violence. I think violence begets violence. And I know some people disagree with me, but I think that we’ve got to get to a place where we talk, but we got to talk honestly, Aaron, we got to sit down and put our guard down, stop defending and debating it, hating it, just sit down and listen and hear. And once we do that, and that’s what the talk does, it draws us in emotionally, once we do that and let our emotions be on the table, then we can be family. And you know, when you have family, you disagree with some people in your family and that’s okay, but they’re family, you’re not going anywhere because we’re family and we stay together and figure this thing out together.

Keck: Sonnykelly.com is the website. If you want more information about ‘The Talk’ or about Sonny, we’ve got to wrap up, but, final thoughts?

Kelly: I just want to encourage people to see the heart of the matter and allow yourself to feel, allow whatever you’re feeling to be what is, and let’s expect that we will find neighbors and friends who don’t look like us, who will affirm us. I know it’s a challenging thing to ask for, but if we can find a way to make spaces that are spaces of resilience, where we will just hear people’s hurt, let them tell their stories first and foremost, then we can come to understanding. Seek first to understand. Let’s see if we can do that — and that’s a great start.

Keck: Sonny Kelly, thank you so much for being with us and for all you’re saying and all you’re doing.

Kelly: Thank you, God bless you, Aaron. Thanks, as always, for what you’re doing. I will be back.