Months before Neil Armstrong uttered “one small step for man,” he and Buzz Aldrin were in Chapel Hill for an important step in their preparation before making history.

They were two of the 62 astronauts who trained at Morehead Planetarium in celestial navigation, also called star navigation. Between 1959 and 1975, nearly every American astronaut who traveled in space visited the planetarium to complete hours of training needed to identify and chart stars. Eleven of the 12 people who ever visited the moon’s surface first stopped through Chapel Hill to train.

Morehead Planetarium historian and educator Michael Neece says one of the reasons it was selected to be the regular site was location.

“Can you imagine the astronauts having to fly up to Chicago, New York or Boston to one of the other major facilities in the world, and having to brave the traffic, fight through the congestion to get to those [places],” he says. “Chapel Hill just made a lot more sense because at the time they started coming here to train, it was a town of 12,000 people as opposed to one of those metropolitan centers that had millions.”

Morehead had some of the best technology in the world, but they also had a director who was willing to craft anything to help the astronauts train more effectively. Tony Jenzano, who started at Morehead in 1951, invented technology tailored to what the Gemini and Apollo programs needed. Neece says Jenzano’s efforts, which let the astronauts study a simulated sky from training chairs mimicking the ones in their shuttles, made a significant difference.

“In both of those instances,” Neece says, “they had the ability of swiveling, tilting back and forth, and doing everything they needed. By all accounts, he was a mechanical genius.”

Neece says all the astronauts trained at Morehead used their star navigation from the planetarium while in space. A handful of times, however, the training prevented emergencies. Neese says the Apollo 8 mission is a good example because Jim Lovell, who trained seven times at Morehead, had to realign the spacecraft every day with the computer system’s navigation and kept a cool head when things went wrong.

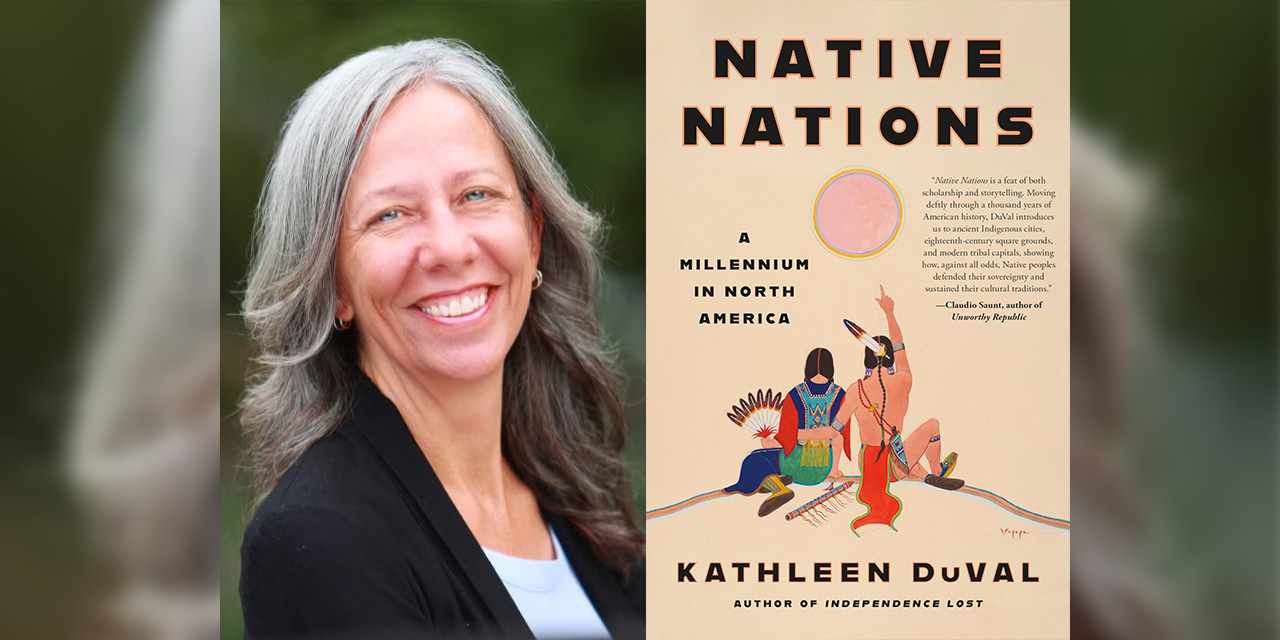

Astronauts train with star navigation devices in Morehead Planetarium (Photo via Morehead Planetarium.)

“At one point, [Lovell] mistakenly reset the navigation platform to think it was back on the launchpad in Florida,” says Neece. “He really had to overcome that and tell the guidance system, ‘hang on, we’re actually in space, let’s re-calibrate.’ He had to use his Morehead training significantly during that.”

The contract Morehead had with the astronauts was open-ended and flexible to whatever or whenever they needed to train. But the planetarium created one rule.

“The only caveat is that Morehead is a facility dedicated to the education of North Carolinians,” Neece says. “That means if there was a schedule program, especially kids’ programs, they never interrupted those. We would always make sure [there were other things to do], like, ‘hey, you’re in town a little early. Why don’t you go play handball down at the gym?’ Or, ‘hey, let’s all go to the Rathskeller to grab a drink and a piece of pizza, and when the show’s over, come back.’”

Neese calls the moon landing a “species milestone.” Despite happening five decades ago, he says it’s still important because of how it should inspire the world to return to the cosmos.

“I think the moon landing is as significant today as it has ever been,” Neece says, “because it’s that symbol of our ability to become more than what we think we can be.”