Editors Note: All photos captions are Cornell Watson’s own words. Some images may be unsettling to readers.

A dispute between a Durham photographer and the Sonja Haynes Stone Center led to a photo exhibition being canceled days before it was set to debut on UNC’s campus.

Documentary photographer and creative artist Cornell Watson was set to have his photo series “Tarred Healing” open this week at the Sonja Haynes Stone Center. Watson described the project as, “an opportunity for Black Chapel Hill to be honored and have their stories told unapologetically.” UNC later cancelled his exhibit following a publication of the photos in The Washington Post.

Watson’s past work has been featured in the New York Times and The Washington Post. He said the Stone Center reached out about a residency following a photo story in The Washington Post titled “Behind the Mask.”

Watson accepted an offer in June 2021 to join the Stone Center as the Fall 2021 Visiting Artist in the Robert and Sally Brown Gallery Museum.

An initial offer letter was sent June 4 from Joseph Jordan, Director of the Stone Center, that had a de-facto agreement with Watson. In the email, which was review by Chapelboro, Jordan asked Watson to use his talents to create an exhibit focusing on “spaces of memory” around the UNC Black community.

He wrote that the university was engaging in self-examination of the Black presence on campus, but more of the story still needed to be told through a “critical lens.”

“Tarred Healing” includes photos using the segregated Old Chapel Hill Cemetery, the murder of James Cates in 1970 and the Rogers-Eubanks community. Additionally, three photos depicted student demonstrations surrounding the UNC Board of Trustees’ inaction around granting tenure to journalist and prospective faculty member Nikole Hannah-Jones. Two others depicted the Unsung Founders Memorial, an installation honoring the free and enslaved Black people who built UNC’s campus.

Old Chapel Hill Cemetery, located on the campus of The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, is a segregated cemetery. The Black side of the cemetery is the burial site of free and enslaved people. A fieldstone often marked enslaved Black people’s burials. According to the Town of Chapel Hill website, the Black side of the cemetery has been vandalized on several occasions. One incident described the Black side of the cemetery being used as parking for a football game in 1985 against Clemson. Resting in peace is a privilege some people do not get. (Cornell Watson)

The Rogers Eubanks community is a historically Black community in Chapel Hill, NC where Black families have lived and thrived since the mid-1800’s. In 1972 Orange County built a landfill next to Roger Eubanks and the community suffered from the negative environmental impacts on the air, water, and quality of life. One of the major concerns was toxins from the landfill leaching into the community’s groundwater. Citizens of Rogers Eubanks described changes to the color and smell of their water. While county water ran through surrounding neighborhoods, it stopped at Roger Eubanks’ door. For over 40 years, this community fought against the environmental injustices ravishing their community. After community leaders successfully advocated to shut down part of the landfill operations and bring clean water to the community, Roger Eubanks began to flourish again. Pictured is community activist Minister Robert Campbell. (Cornell Watson)

Watson said he sent the full photo story to the Stone Center on December 21. In the submission, he included reviews he got from other photojournalists.

When he got reviews from the center’s leadership, Watson learned they preferred to exclude four of his photos.

“Originally they wanted to exclude one of the first photos that I showed them,” Watson said. “[It was] the photo of the Unsung Founders Memorial and the reinterpretation of Silent Sam and that forced perspective. I had initially showed that to them not long after I made it in July. And so that was an ongoing disagreement.”

Unsung Founders Memorial, an installation to commemorate and honor the free and enslaved Black people who built America’s first public university, was installed a few yards away from Silent Sam, a Confederate statue, on The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill campus in 2004. Created by artist, Do Ho Suh, Unsung founders memorial low tabletop design juxtaposed to the towering monument of white supremacy forced its viewers to take in the full history of UNC Chapel Hill. Together in the same space, the two monuments served as an accurate portrayal of Black people’s resilience, determination, and achievements despite the weight, trauma, and terror of white supremacy. While the statue was toppled in 2018, white supremacy in its many forms still hovers on these grounds, on our people.

While creating the photo of the Unsung Founders Memorial with an interpretation of Silent Sam in June 2021, I was approached by campus police. I was questioned, asked to present my ID, and without permission, they recorded my information. Several weeks later white supremacists gathered at the Unsung Founders Memorial and sat on it with Confederate flags. According to numerous witnesses, campus police did not approach, question, or ask for their identification. Days later the Unsung Founders Memorial was fenced off with barricades. (Cornell Watson)

The Unsung Founders Memorial, a memorial to honor the free and enslaved Black people who built The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, was surrounded by barricades several weeks after white supremacists gathered at the memorial and sat on it with Confederate flags. (Cornell Watson)

“I pushed back and I told them that it was censorship,” Watson said.

The other photos the university wanted to exclude, Watson said, were a trio depicting protests in support of Nikole Hannah-Jones. Watson said the university’s reasoning was that the photos were not part of the story.

Clayton Sommers, Vice Chancellor for Public Affairs and Secretary of The University for the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, stares as Black students lead a demonstration during the board of trustee meeting to make a tenure decision for Nikole Hannah-Jones. In 1979 Black students lead a similar demonstration when a qualified Black professor, Sonya Haynes Stone, was denied tenure. (Cornell Watson)

Julia Clark, Vice President of the Black Student Movement at The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, leads a demonstration on campus to protest the University decision not to give Nikole Hannah-Jones tenure. Their demands included tenure for Nikole Hannah-Jones, more diversity on the board of trustees, a memorial for James Cates Jr., protection for the Unsung Founders Memorial, and safety for Black students on campus. (Cornell Watson)

Often when we think about healing, it excludes the unrest we experience. When our bodies heal from viruses, they are in a constant state of fighting. They release white blood cells that attack threats to our health and existence. It’s what we saw through Black students demonstrations about the lack of recognition for James Cates Jr., Nikole Hannah Jones tenure, the lack of university protection from white supremacists, and systems of whiteness that prevent us from fully existing. Fighting is a part of healing. (Cornell Watson)

In a written statement from the UNC Stone Center they said their vision for the project was to celebrate and remember the descendants of Black Chapel Hill.

“We here at the Stone Center felt, however, that although a great deal was being done to research and uncover significant sites on campus and in and around Chapel Hill, very little had been done to afford those descendants, for whom those sites are sacred, an opportunity to sacralize them. And, to give the various communities who’d urged and supported the various processes of ‘reckoning’ on campus and in the community, the same opportunity to honor those sites and the people whose lives are deeply invested in those sites. That was the focus for this exhibition and those were the lives, both departed and still with us, that we wanted to celebrate with this exhibition and that is what was conveyed to Mr. Watson at every step of this process.”

Thursday’s statement acknowledged disagreements over the scope and content of the exhibit’s story.

“We chose a set of remarkably beautiful and evocative photographs from the selection [Watson] presented that captured the depth and meaning we’d hoped to achieve with this show. It would almost be more appropriate to say those prints were breathtaking. There were several, however, we felt ran totally counter to what we were trying to achieve and would detract from the theme, and indeed from the atmosphere of reverence and the sacred that we wanted to create for the families and individuals pictured in the show.”

Watson told Chapelboro he believes the ongoing efforts of the Black Student Movement at UNC are a key point of the story.

“They’re part of the university’s legacy,” Watson said. “They’re deeply tied to a lot of the spaces that were included in the photo story. I was struggling with how they couldn’t recognize how much they were a part of the story.”

Watson said the situation weighed heavily on him. He said his initial mindset was the story should be the full body of work or nothing at all.

“This really is cutting my values, not just as an artist, but as a person,” Watson said. “As an artist, the whole point of art is to be able have artistic expression and to limit it is very disappointing.”

The Stone Center and Watson later came to an agreement allowing the Unsung Founders Memorial photo to be included in his photo series. Watson decided to move forward with the exhibition with the protest photos excluded as he said he believed the rest of the story needed to be told.

According to Watson, the gallery was slated to open in the third week of January. He said that month, he reached out to a photo editor at The Washington Post to get their feedback. The editor expressed interest in publishing the full story – which Watson expected to happen sometime in February after the exhibition. Watson said he did not alert the university that he had submitted the photo series to The Washington Post.

The exhibition was later delayed with a new opening date of February 22. Watson’s photo story was published in The Washington Post on February 18.

That same day, Watson received a three-sentence email from Jordan saying his exhibition was cancelled. The director wrote saying someone sent a copy of The Post article and the center had decided not to mount the exhibit.

Watson said he waited to reply to “remove emotions” from his response which then asked for clarification on the eleventh-hour cancelation. Jordan responded saying the details in The Post article ran counter to agreements about how the exhibition was to be presented to the public.

The Stone Center’s written statement cited the same rationale.

“We were not consulted and had no prior knowledge of Mr. Watson’s submission to the Post. We, of course, were taken aback by these events. Under these circumstances and given Mr. Watson’s actions, that ran counter to our understandings, we felt it necessary to cancel our show. We had no assurances or indications from Mr. Watson about his intentions going forward and we could not be certain if it would be mounted again in a form or format that would run counter to our original vision, or displayed with the title we developed, which was specific to our vision.”

Watson said the decision came as a surprise since he and the university had never discussed the limits of the work outside of UNC nor signed a contract.

“I own the work and have not granted anyone exclusive licenses for usage, including the university,” Watson said.

On Wednesday, Watson’s photos were seen on the floor of the Stone Center in a photo shared on social media. The gallery windows have since been covered.

The @UNCStoneCenter was founded “to support the critical examination of all dimensions of African-American and African Diaspora cultures.” Cornell’s images are at the Stone Center—sitting on the floor. pic.twitter.com/KjxJLBURxs

— Kate Medley (@katemedley) February 23, 2022

“It feels petty,” Watson said. “I don’t really know another way to describe it. The photos are there. It is not like people were gonna not come because they saw photos on a Washington Post story. If anything, people were gonna come because they saw the photos in a Washington Post story.”

A map of Old Chapel Hill cemetery located on the campus of The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. (Cornell Watson)

Broken headstones on the Black side of Old Chapel Hill Cemetery located on the campus of The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. (Cornell Watson)

Pit: a hole, shaft, or cavity in the ground.

Outside of the student union during an interracial dance, white supremacists stabbed James Lewis Cates Jr. to death in the area of The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill campus referred to as ”The Pit” in 1970. On that night, they didn’t just murder a son, a grandson, and a friend of many in the Chapel Hill community; they murdered an angel. The murder of James Cates left more than a hole in the ground. It showed us a hole in the system supposed to protect and serve us when they allowed the white supremacists to go home. It showed us a hole in our medical system when an ambulance arrived 40 minutes after he was stabbed. It showed us the hole in our justice system when not one single person was held accountable for his murder. It has shown us that the willfully blinded will try to leave a hole in our history and peace by not acknowledging what happened in this space. (Cornell Watson)

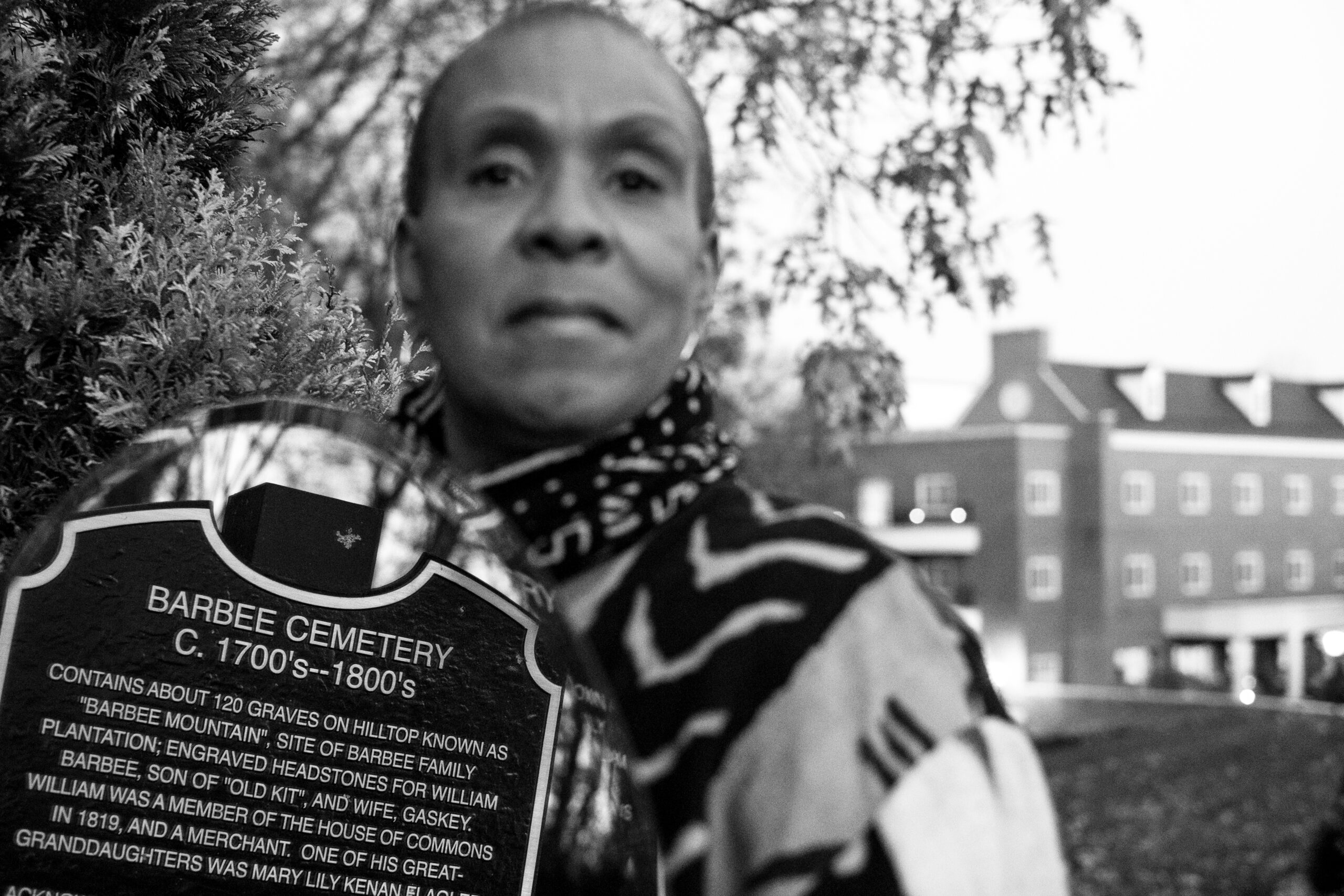

The Rizzo Center, The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Kenan-Flagler business school resort, is located on a former slave plantation. Next to the hotel resort in a wooded area is Barbee Cemetery. The cemetery contains over 100 unmarked graves of enslaved Black people who helped build UNC-Chapel Hill. A Barbee cemetery info marker is tucked behind a tree away from the center and out of sight. While it makes mention of the graves and plantation, it does not make any mention of slavery

or Black people.

A descendant of the enslaved Black people of the Barbee Family and community activist Lorie Clark stands in front of the Rizzo center with a reflection of the cemetery sign. (Cornell Watson)

Toney and Nellie Strayhorn, both freed from slavery, purchased a small plot of land on the outskirts of Chapel Hill in Carrboro, NC, named after white supremacist Julian Carr, in the mid 1870’s. They built a one-room cabin that eventually expanded to a two-story home. The family survived and thrived through the racial violent times of Reconstruction and Jim Crow.

Dolores Clark (centered) sits with her children and great-grandchildren in the home her great-grandparents, Toney and Nellie Strayhorn (pictured on the wall), built around 1879 in Carrboro, North Carolina. (Cornell Watson)

David Caldwell, Jr. a community activist and lifelong resident of Rogers-Eubanks stands in front of the Rogers Road community center. The community center provides services such as after-school tutoring, a food bank, adult ESL classes, senior lunches, and children’s summer camp. (Cornell Watson)

While “Tarred Healing” will not show in the Stone Center gallery, Watson said he has received an offer from the Chapel Hill Public Library to exhibit his work. He said he wishes the circumstances were different, but he has no regrets on his approach to the photos.

“The work was supposed to happen,” Watson said. “I was supposed to work on that [project] and put those photos together for the community. That was supposed to happen. I also don’t regret sending the photos to The Post. I don’t regret any of those decisions.”

The Stone Center wished well to Watson in his future endeavors – especially as the two share common goals in honoring the Black community within Chapel Hill’s history.

“As happens so often in artistic collaboration, there were disagreements in process; but there is no disagreement around our shared purpose of foregrounding the lives and stories of Black people in our communities,” the Stone Center statement read. “We share a deep-rooted agreement – one enshrined in the mission of the Stone Center – that we should reckon with, remember, and honor the Black community’s role and contribution to the University’s history. We intend to continue our efforts to support talented and visionary artists who are interested in principled examinations of the lives of people of African descent.”

To read the full UNC Sonja Haynes Stone Center statement, click here.

Photos via Cornell Watson

Chapelboro.com does not charge subscription fees, and you can directly support our efforts in local journalism here. Want more of what you see on Chapelboro? Let us bring free local news and community information to you by signing up for our biweekly newsletter.