A federal judge invalidated part of North Carolina elections law that allows one voter to challenge another’s residency, a provision that activist groups used to scrub thousands of names from rolls ahead of the 2016 elections.

U.S. District Judge Loretta Biggs said in an order signed Wednesday that the residency challenges are pre-empted by the 1993 federal “motor voter” law aimed at expanding voting opportunities.

The National Voter Registration Act “encourages the participation of qualified voters in federal elections by mandating certain procedures designed to reduce the risk that a voter’s registration might be erroneously canceled. Defendants’ conduct contravened these procedures,” Biggs wrote.

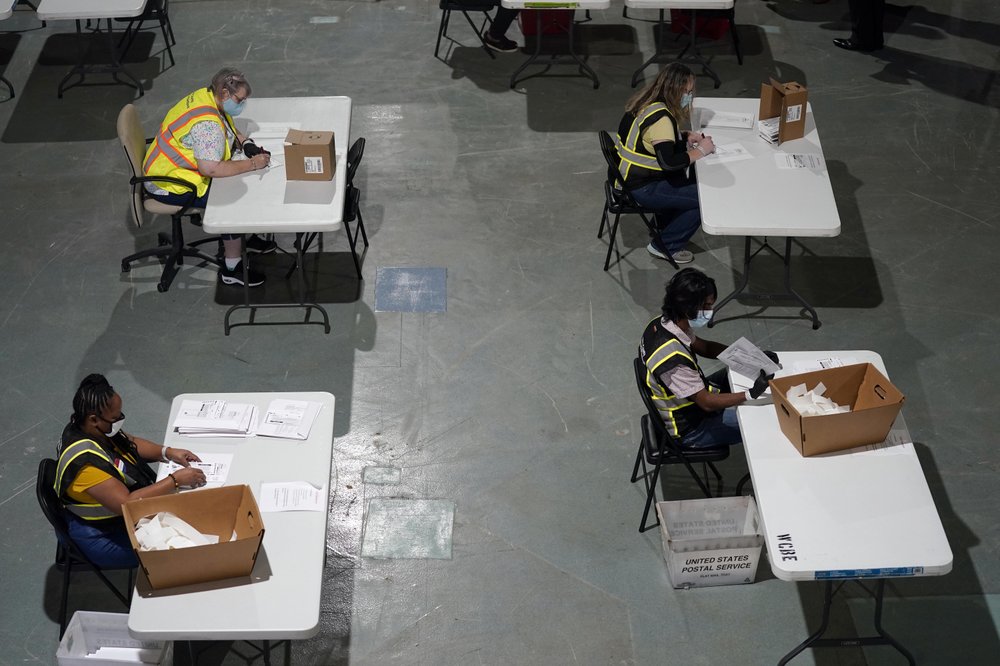

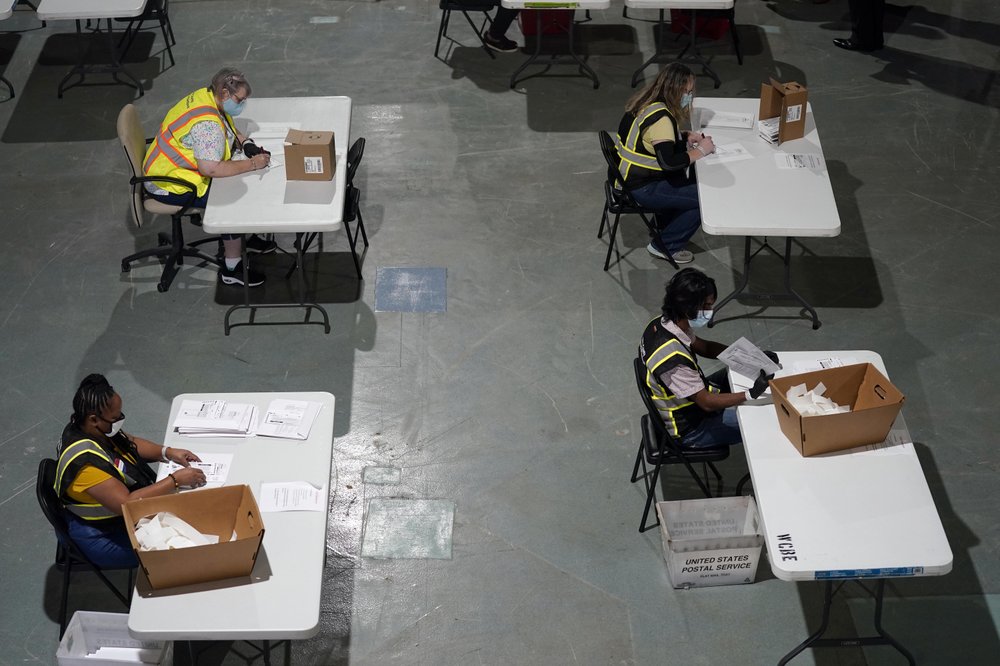

Biggs had ordered days before the 2016 elections that Cumberland, Moore and Beaufort counties restore thousands of canceled voter registrations. She acted after the NAACP and others sued, alleging the purge of voter rolls disproportionately targeted blacks. Biggs concluded then that the three counties had purged between 3,500 and 4,000 voters from registration rolls since August 2016.

The people who had challenged valid residency of voters filing challenges in Cumberland and Moore counties were volunteers with the Voter Integrity Project. The group’s North Carolina director, Jay Delancy, said it was part of an effort to reduce the potential for voter fraud.

“We followed North Carolina law scrupulously in filing more than 6,000 individualized voter challenges in 2016 and the local election boards acted properly in sustaining those challenges,” he said Wednesday. He said his group would ask state legislators to revise the law “to empower private citizens wishing to detect and challenge illegal voters.”

Moore County Attorney Misty Leland said her county’s elections board had done as the state law required and the state elections board directed. Attorneys for Beaufort and Cumberland counties did not respond to invitations to comment.

In most cases cited by the NAACP lawsuit, residency challenges followed after mail to a voter was returned as undeliverable. County elections boards can accept returned mail as evidence that the voter doesn’t live there. That resulted in a hearing at which challengers presented evidence, according to a state legal filing. If local officials found probable cause, the challenged voter was given notice of a subsequent hearing. A voter who doesn’t rebut the evidence can be removed.

“By purging dozens and sometimes hundreds of voters at a time based on returned postcards, the state was disenfranchising eligible voters and violating federal law. This ruling ensures an end to this illegal practice,” plaintiff’s attorney Leah Kang wrote in an email.

Related Stories

‹

Several States Are Making Late Changes to Election Rules, Even as Voting Is Set To BeginNew or recently altered state laws are changing how Americans will vote, tally ballots, and administer and certify November’s election.

DA Says Libel Case Against N. Carolina Attorney General OverWritten by GARY D. ROBERTSON A North Carolina prosecutor said Thursday that campaign-related charges won’t be pursued further against Attorney General Josh Stein or his aides, one day after an appeals court ruled the political libel law her office was seeking to enforce is most likely unconstitutional. Wake County District Attorney Lorrin Freeman said that the ongoing […]

Judge Blocks Campaign Law Enforcement in AG Campaign ProbeWritten by GARY D. ROBERTSON A federal judge agreed on Monday to block for now any enforcement of a state law in a political ad investigation of North Carolina Attorney General Josh Stein’s campaign, saying it’s likely to win on legal claims that the law is unconstitutional. Following a court hearing in Greensboro, U.S. District […]

NC Republicans Advance Bill Limiting Mail-in Ballot CountingWritten by BRYAN ANDERSON With the legislative year nearing an end, North Carolina Republicans on Wednesday advanced a string of measures that voting rights groups fear would prevent lawfully cast ballots from being counted and discourage participation in the 2022 election. The bills the GOP moved through the House rules committee are unlikely to become law, […]

North Carolina Lawmakers Focus On Guns, Immigration and Parental Rights Ahead of a Key DeadlineThe crossover deadline has passed for bills in the North Carolina General Assembly. What are some of the themes seen in this session?

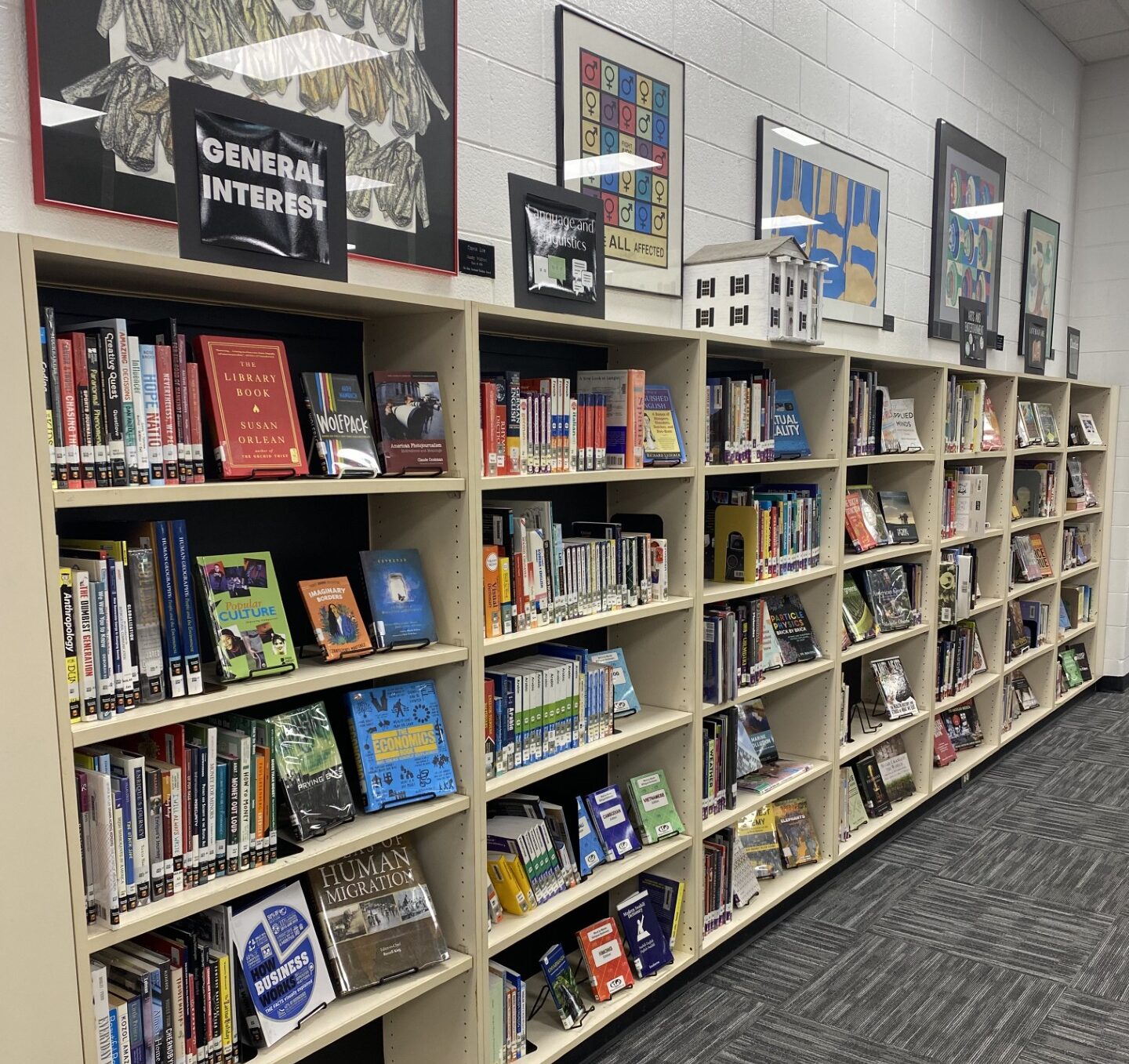

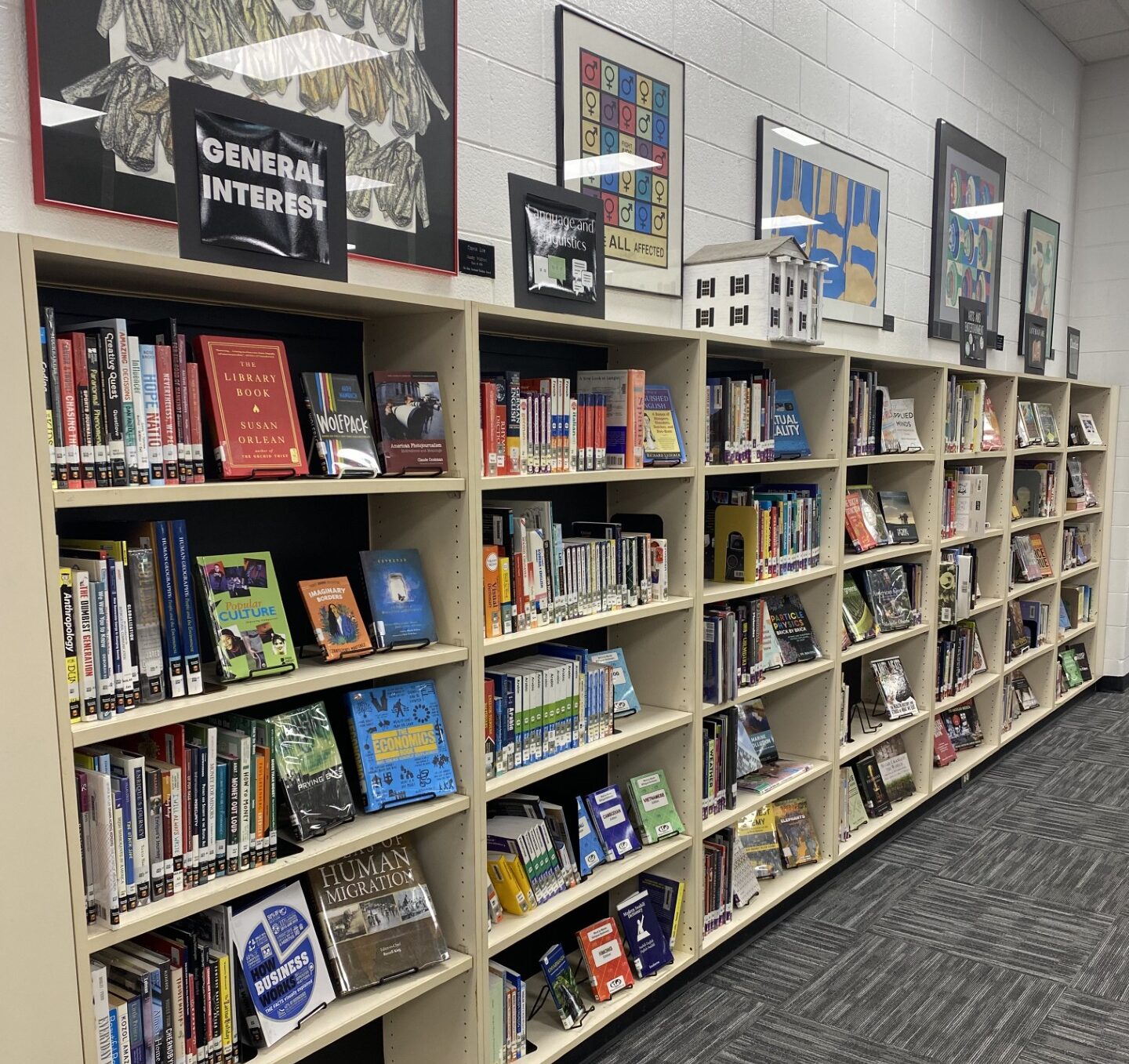

'Where Do We Draw the Line?': NC Legislation Targets Public School LibrariesIn this legislative session, North Carolina Republican lawmakers sponsored bills that would allow more control over public school libraries.

The Election Director in North Carolina, A Key Swing State, Is Ousted After a Republican Power PlayThe North Carolina elections board ousted its executive director Wednesday in a partisan move that now puts Republicans in control.

Republican Concedes Long-Unsettled North Carolina Court Election to Democratic IncumbentThe Republican challenger for a North Carolina Supreme Court seat conceded last November’s election to Democratic opponent Allison Riggs.

Federal Judge Says Results of North Carolina Court Race With Democrat Ahead Must Be CertifiedDisputed ballots in the still unresolved 2024 race for a North Carolina Supreme Court seat must remain in the final count, a federal judge ruled late Monday.

North Carolina Republicans Already Seek to Tighten Up 2024 Immigration Enforcement LawNorth Carolina Republicans want a 2024 deportation law tightened further as President Donald Trump's national immigration crackdown builds.

›

Comments on Chapelboro are moderated according to our Community Guidelines